Alchemy in Christian Art: The Philosopher’s Stone and the Virgin’s Vessel

“This exploration delves into Alchemy in Christian Art, examining how artists like Filippo Lippi infused their works with imagery to express sacred transformation and alchemical symbolism.”

In the dim hush of Florence’s San Lorenzo, within the Martelli Chapel, a painting waits. It does not shout. It does not dazzle with celestial choirs or flame. But for the one who stands still before it, Filippo Lippi’s Annunciazione Martelli begins to move inward, like a liturgy. There, in the centre, between an angel and a Virgin, rests an object few notice and fewer understand: a transparent glass vessel filled with water, placed deliberately within the Annunciation of the Incarnation.

In keeping with centuries of Roman Christian iconography, the angel is the Archangel Gabriel, the divine messenger. His presence is not poetic invention but drawn directly from the Gospel of Luke, where he is sent to Mary with the most profound proclamation ever made to human ears. Gabriel’s name means “God is my strength”, and in theological tradition, he is the angel of revelation, of divine speech, of Annunciation itself. In Lippi’s painting, he raises his hand not merely in greeting but in the act of divine declaration. His Word becomes the Seed—the message, the moment of metaphysical conception.

The image is delicate. Mary, haloed and modest, listens as the Word of God enters her silence. The architecture is clean, and the geometry precise. But this stillness conceals a metaphysical storm. In the middle of it, the glass—fragile, perfect, whole—stands like a cypher, holding the mystery of how spirit enters matter without rupture. It is a theological thesis rendered in silence.

And yet, this is not a mere visual metaphor for virginity. The glass pelican, rendered with almost scientific clarity, is no accident. It is, rather, the meeting point of Roman Catholic metaphysics, Marian mysticism, and a quiet undercurrent of alchemical symbolism that runs through Lippi’s works for his Medici patrons. In the right light, this vessel becomes a retort, a womb, a soul. Through it, the infinite is distilled into form.

The Glass Vessel: More Than Ornament

From Aquinas to Bernard of Clairvaux, the metaphysics of Mary has occupied some of the most precise minds of Christendom. She is not merely the Mother of God—she is the ontological threshold—the place where uncreated being passes into created nature. In Scholastic thought, Mary is materia sanctificata—sanctified matter uniquely disposed to receive divine form. She is the vas Dei, the Vessel of God.

In Lippi’s Annunciazione Martelli, this theology is made visible. The glass pelican flask, filled with water, stands as a perfect analogue for Mary herself: clear, incorruptible, open, and unbroken. Just as light passes through the vessel without shattering it, so the Logos enters Mary’s womb. The Word becomes flesh, and the vessel remains intact.

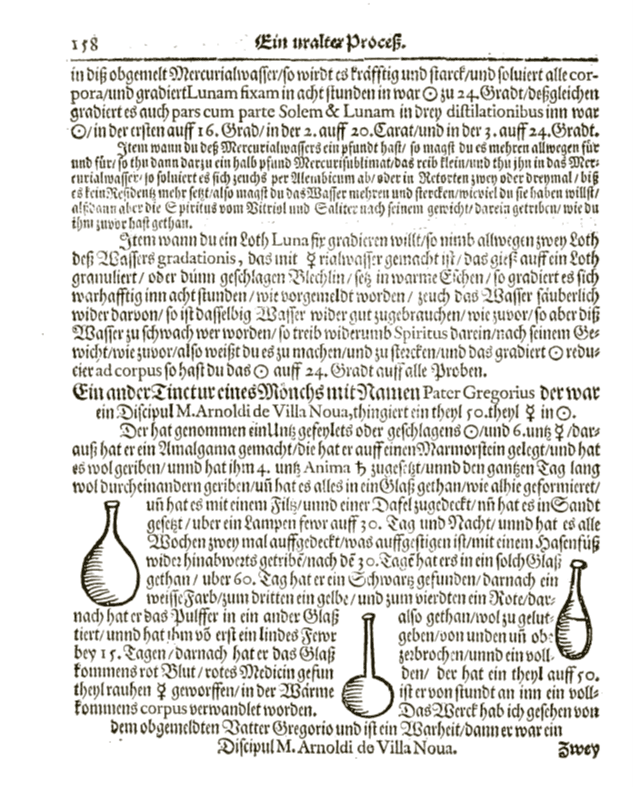

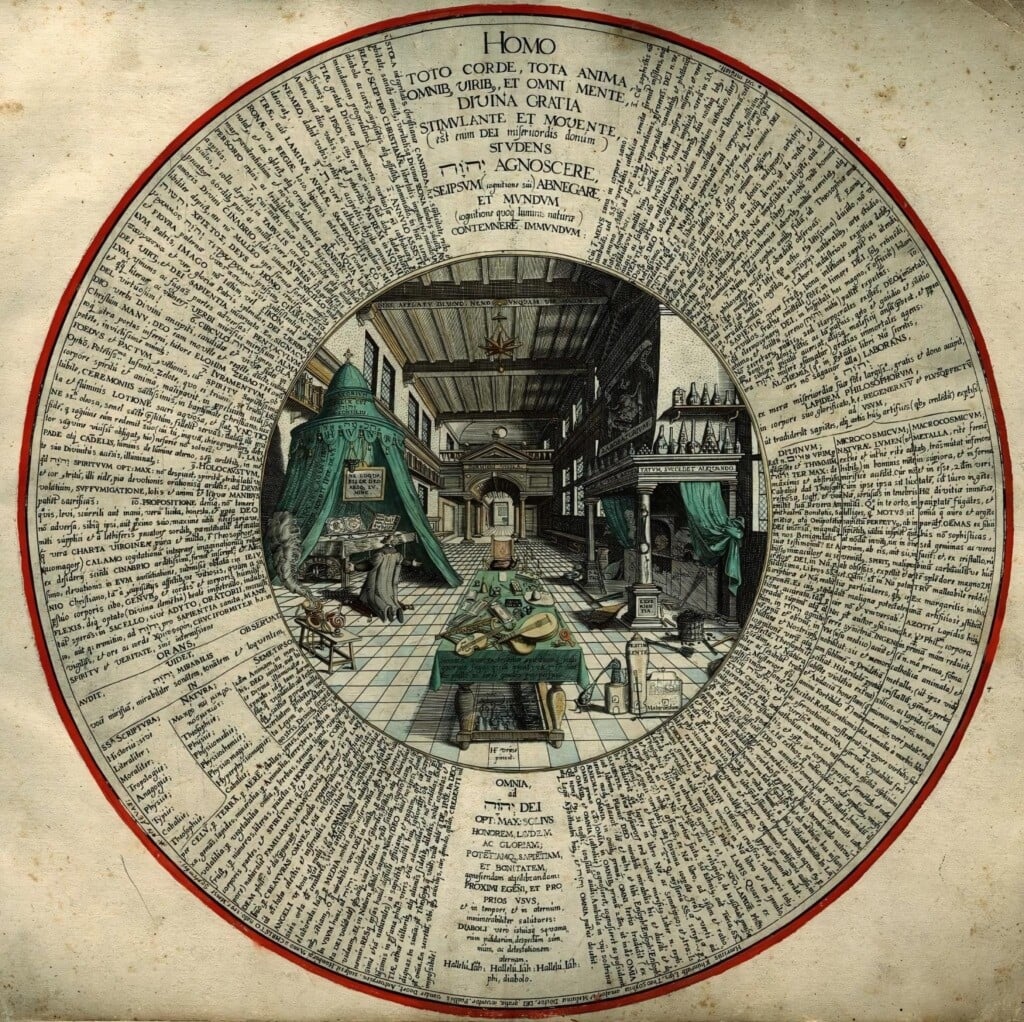

The visual echo is precise. The flask’s shape, with its narrow neck and swelling belly, recalls the design of alchemical glassware used in the distillation of tinctures and essences—particularly the pelican or the cucurbit. These were not merely functional tools of the laboratory, but ritual instruments, used to imitate nature’s work in miniature. In both Christian mysticism and alchemical theory, the vessel must be pure, sealed, and receptive—a matrix within which matter is transformed.

The Eucharistic Pelican and the Alchemical Retort

This link is not conjecture. In the language of alchemical emblems and monastic poetry alike, the symbol of the pelican—who wounds her breast to feed her young—was merged with the imagery of Christ. As St Thomas Aquinas writes in his Eucharistic hymn Adoro Te Devote:

Pie pellicane, Iesu Domine,

Me immundum munda tuo sanguine

“Pious pelican, Lord Jesus,

Cleanse me, the unclean, with Your blood.”

In both cases—the lab and the liturgy—the symbol speaks of self-sacrifice for transformation. The pelican, like the crucified Christ, feeds from its own essence. In alchemical practice, the pelican flask performs a similar function: it circulates its own vapours, refining itself through inward motion, until what was base becomes pure. The vessel is not merely a container—it is the agent of change.

This avian allegory has deep roots in the medieval bestiary tradition, where the pelican was believed to strike its own breast in times of famine, reviving its dying young with its own blood. This image was taken up by Church Fathers as a symbol of Christ’s redemptive death, especially in relation to the Eucharist, where the faithful are nourished by the Body and Blood of the Saviour. In visual art and sacred architecture, the pelican became a familiar motif on altars, chalices, and choir stalls, forming part of a Eucharistic metaphysics in which divine life is given by means of internal sacrifice. This spiritual logic is mirrored in alchemy, where the sealed vessel must destroy and renew itself within. The pelican flask, like the wounded bird, becomes the locus of transformation—a space in which the material is cooked by its own internal fire, broken down, and recombined into something incorruptible.

Just as the pelican Christ gives of His blood to raise the fallen, so too the alchemical pelican must bleed its contents through repeated circulation to produce the tincture that heals, transfigures, and makes whole. The mythic image of the pelican was first immortalised in the early Christian text Physiologus, composed in the 3rd or 4th century, where it is said the bird strikes down its disobedient young—only to restore them to life with its own blood after three days. The author, drawing on Romans 1:25, likens this act to the arc of salvation: humankind, having turned from the Creator to the creation, is chastened, then redeemed through the sacrifice of Christ. The pelican thus becomes a living allegory of divine mercy.

“This motif passed into countless medieval bestiaries and devotional treatises—from Guillaume le Clerc to Bartholomaeus Anglicus—and found fertile ground in Christian art. Painted on tabernacle doors or crowning late-medieval Crucifixions, the self-wounding bird became a Eucharistic sign: the loving Redeemer who feeds the faithful from His broken flesh, and who, like the alchemical flask, undergoes a circulatory passion to bring forth eternal life.”

From Annunciation to Adoration: The Arc of Manifestation

Lippi did not stop with the Annunciation. His Adorations—most notably the Adoration of the Christ Child and the Adoration of the Magi—form a contemplative sequence when read alongside the Annunciazione Martelli. The Adoration scenes move from the moment of mystical conception to the epiphany of embodiment. In these paintings, the Christ child is not tucked away in swaddling or seated on Mary’s lap. He is often placed directly on the bare ground, echoing the alchemical doctrine of coagulatio—spirit made dense, descending into matter, manifesting in the very dust of the world. The onlookers kneel not just in devotion, but in spiritual recognition. The divine that was hidden is now visible.

This sequence unfolds as a kind of philosophical drama in two acts. In the Annunciation, we are invited into the invisible mystery of divine ingress—the infusion of the Logos into the soul. It is a moment governed by metaphysical silence, by the stillness of being before becoming. In the Adoration, that hidden reality achieves formal presence. The soul’s receptive moment becomes vision, and the Word becomes not only flesh but image. The child, lying vulnerably upon the earth, now radiates a paradoxical kingship: he is the Philosopher’s Stone revealed, and those who kneel before him do so not merely as observers of a birth, but as witnesses to a cosmic operation completed. The viewer, passing from one painting to the next, does not follow a story but a sequence of transfiguration—from invisible light to embodied radiance, from mystery to manifestation.

Mystical Meditation and the Medici Mind

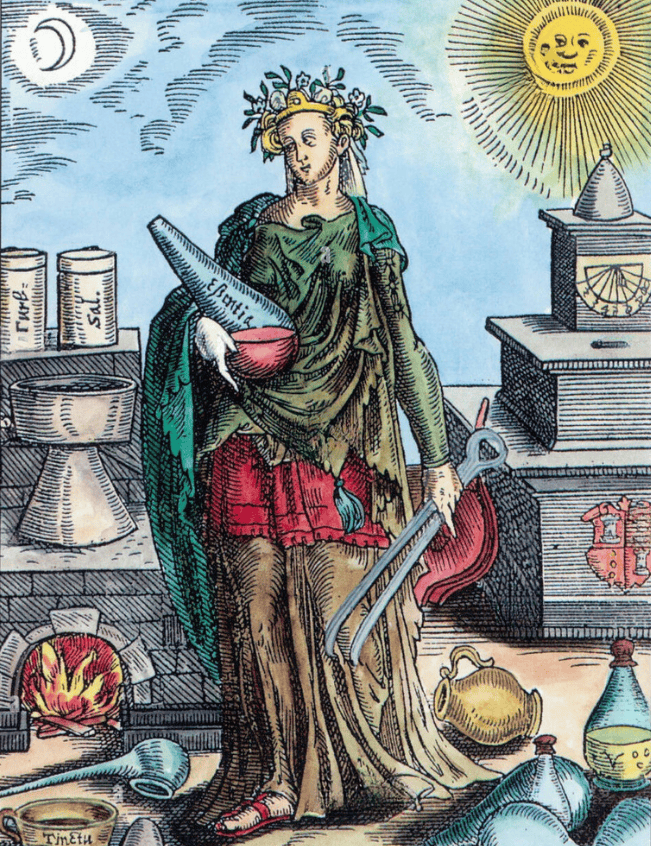

According to Carl A.P. Ruck and Mark Alwin Hoffman, Lippi’s paintings—especially those created under Medici patronage—were designed not merely for veneration, but for mystical meditation. The Medici circle, especially under Cosimo and later Lorenzo, was steeped in Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Christian mystical currents. Ficino, translator of the Corpus Hermeticum, walked the same halls where these paintings were first hung. Their visual logic is not just theological, but initiatory.

Lippi’s works, then, may be read as psycho-spiritual instruments. The Annunciation opens the inward gate—the moment of inward consent. The Adoration offers the fruit of contemplation: the visible, living Christ. This sequence follows not only the rhythm of Scripture, but the steps of inner transformation described in mystical and alchemical texts: purificatio, illuminatio, unio.

The Medici were not merely bankers or politicians—they were architects of a spiritual revival masked in civic patronage. Their chapels became laboratories of the soul, adorned not only to inspire devotion but to guide vision inward. The art they commissioned was meant to elevate the viewer through contemplative seeing. Under their influence, artists like Lippi painted not just for beauty or instruction, but to train the gaze—to discipline the soul through sight, leading the intellect upward from the visible to the intelligible. Within this framework, Lippi’s sacred cycles function as concentric mirrors: theological, philosophical, and esoteric, reflecting the soul back to itself and then beyond itself toward the divine. In this context, to look upon the glass vessel or the newborn child is not simply to witness history, but to enter into a ritual of transmutation, executed in pigments and silence.

The Philosopher’s Stone in a Manger: The Hidden Logic of the Philosophical Stone

To call the Christ child the Philosopher’s Stone is not blasphemy in this tradition. It is fidelity to a long Christian hermetic current in which Christ is the perfected substance, the Stone rejected by the builders that becomes the cornerstone of the New Jerusalem. He is the Lapis Exilis of the Grail legends, the redemptive matter that reconciles opposites.

In Lippi’s symbolic programme, the Christ of the Adoration is not merely adored—he is beheld, incarnated in purified form, surrounded by those whose souls are prepared to see. The infant is more than infant—he is the embodied Logos, coagulated light, divine essence made visible in matter. The painting is not illustration but epiphany.

The Philosophical Stone, in alchemical language, is not merely a mineralogical quest but the total perfection of matter and spirit—the union of opposites in a new and incorruptible form. It is what emerges when the prima materia has passed through the cycles of death, dissolution, recombination, and illumination. It is the end of the Magnum Opus, the goal not of gain, but of transfiguration.

When Christian alchemists spoke of this Stone, they did not seek to rival the Gospels—they sought to interpret them through another tongue: the symbolic language of nature. And in that tongue, the child lying in Lippi’s manger—naked, luminous, and placed on the earth itself—is not only the Son of God. He is the goal of the work, the sign that the transmutation of creation has been achieved.

In this synthesis, Christ becomes the lapis philosophorum not merely because he is divine, but because he perfects and unifies what was divided: heaven and earth, soul and body, eternity and time. He is not gold transmuted from lead, but life drawn from death, the eternal Stone lying in a manger—the secret at the heart of the world, made visible for those who have eyes trained not only to see, but to contemplate.

“Such imagery does not stand in isolation, but belongs to a broader spiritual grammar—one spoken fluently in the sacred visual language of Christian Renaissance art”.

Mary the True Alembic, and Christ Child the Philosopher’s Stone

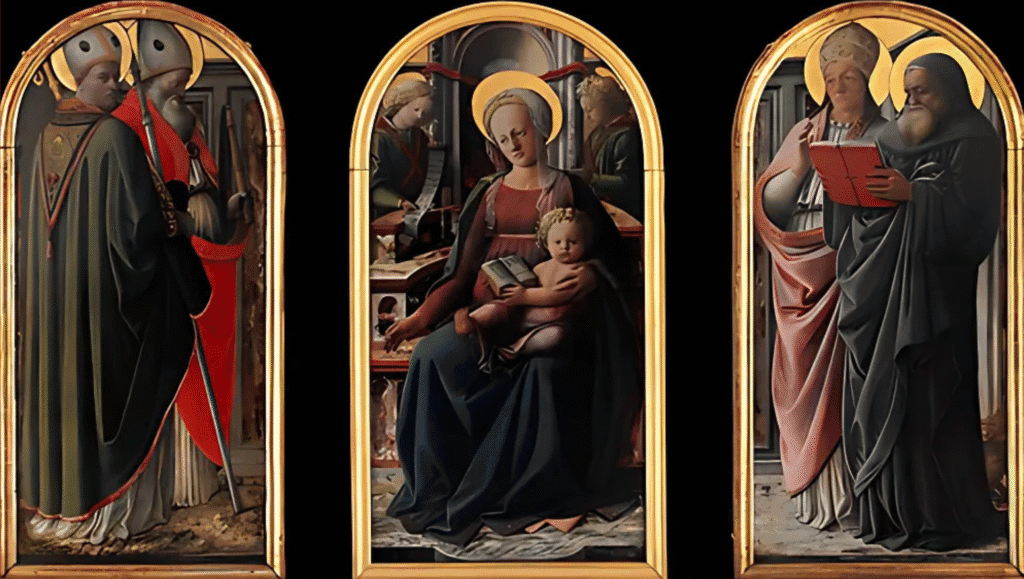

“Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Angels serves as a quintessential example of Alchemy in Christian Art, where theological doctrine meets visual symbolism to evoke mystery and incarnation.”

In The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Angels, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fra Filippo Lippi offers more than a devotional image—he crafts a theologically layered and alchemically resonant vision of the Incarnation. The Virgin sits enthroned not in grandeur but in symbolic subtlety. She is the Throne of Wisdom (Sedes Sapientiae), upon which the Logos rests, not only as a child but as the divine intellect embodied in matter.

This is no static Madonna. The infant Christ moves with vitality, his twisting gesture evoking sculptural dynamism—a likely echo of Donatello’s innovations in sacred sculpture, which introduced psychological realism and corporeal energy into the Florentine visual vocabulary. Lippi, sensitive to these shifts, integrates that same sense of living form, rendering the Christ child not as icon but as active principle — the divine agent entering the visible world.

Mary’s role, however, extends far beyond motherhood. She holds a white rose—the rosa sine spina, “the rose without thorns”—a traditional symbol of her Immaculate Conception, the doctrine that she was preserved from original sin. In Roman Catholic theology, she is the purified matter, the materia sanctificata, the living vessel made incorruptible by divine foreknowledge. The rose, unblemished by the curse of Eden, signifies the transfigured earth, the ground made capable of bearing divine fruit.

But the rose is also an alchemical emblem. In the symbolic language of Christian alchemy, the rose represents spiritual rebirth, illumined matter, and the perfection of the soul through divine fire. As the Rose of the World, Mary becomes the garden in which the Stone is born—the philosopher’s matrix—the mystical vessel through whom the divine tincture is made flesh. She is both the womb and the retort, the matrix and the mystery.

An angel behind her unfurls a scroll bearing the words of Ecclesiasticus (Sirach 24:19): “Come over to me, all ye that desire me, and be filled with my fruits.” In the tradition of both Church and Hermetic Christianity, this is the voice of Wisdom—Sophia—inviting the soul to partake in divine nourishment. The scroll is not simply Scripture: it is a verbal sacrament, initiating the viewer into a contemplative encounter with the hidden divine. In this light, Mary becomes the alchemical garden, the one in whom divine Wisdom is not only conceived, but also offered to those prepared to receive it.

Originally the central panel of a now-dispersed triptych, this painting would have served as the axis of a larger theological meditation. Its placement in sacred space implies its function: not simply as ornament, but as visual liturgy—a work of Christian Renaissance alchemy in which matter and meaning are transmuted before the viewer’s eye. Lippi’s characteristic attention to Netherlandish light and surface—especially his transparent veils and radiant skin tones—renders the flesh of the Virgin and Child as spiritually clarified substance, touched by light, yet grounded in earth.

This is the alchemical theology of the Roman Church in pictorial form: the divine fire descends into the pure vessel, and from that union, the Stone is born—not in a crucible, but in the womb of the Virgin. The Christ child is the completed work, the Lapis Christi, the gold of heaven, born through a vessel untouched by the corruption of lead. In Lippi’s painting, the Virgin’s body becomes the true alembic, and the Christ child, twisting in grace, is not only the Son but the Philosopher’s Stone, perfected and radiant, ready to be beheld.

“Fra Filippo Lippi’s single panel offers a microcosm of the spiritual and symbolic density that defines Christian Renaissance art as a whole—a visual language shaped not only by theology and devotion, but also by an esoteric metaphysics of light, form, and sacred transformation”.

Christian Renaissance Art: A Language of the Invisible

“The Christian Renaissance gave rise to a unique synthesis of theology and image-making—a flowering of Alchemy in Christian Art, in which painters communicated divine truths through the veil of symbolic form.”

Filippo Lippi’s paintings are part of a broader spiritual current within Christian Renaissance art, a tradition that did not separate beauty from theology, nor form from metaphysical function. In this tradition, art was not merely illustrative. It was liturgical, initiatory, even sacramental—a means of encountering what could not be said, only seen.

Rooted in the revival of classical philosophy and fused with the sacramental imagination of the Church, Christian Renaissance art sought to make the invisible intelligible through material form. This was not a betrayal of faith, but its flowering: Neoplatonic ascent, Thomistic realism, and Marian devotion converged to create images capable of guiding the soul toward contemplation. Lippi, like Fra Angelico before him, worked not as a decorator but as a visual theologian, encoding layers of meaning in architectural space, gesture, light, and symbol.

In this context, elements such as the transparent glass vessel or the naked Christ Child lying on bare earth are not aesthetic flourishes. They are theological propositions, rendered in pigment and silence. They invite the viewer to do more than admire—to meditate, to ascend, to participate in the same mystery the image enacts. This is the true character of Christian Renaissance art: it does not merely depict the divine—it offers the conditions by which the divine might be glimpsed.

Through the discipline of vision, the eye becomes alchemical, the image contemplative, and the canvas a portal through which the infinite brushes the edge of form. Lippi’s sacred works, though born of a particular city and patronage, thus remain part of a perennial language—one that speaks still to those who seek transformation not only of gold, but of the heart.

Alchemy in Christian Art: Leonardo, Eyck, and the Hidden Tradition

“Beyond Lippi, numerous artists contributed to the visual tradition of Alchemy in Christian Art, embedding sacred metaphors and transformational imagery within their religious compositions.”

Though this article has centred on the visionary works of Fra Filippo Lippi, he is by no means the only painter whose art bears the imprint of Christian alchemical symbolism. From the luminous Madonnas of Fra Angelico, where light becomes a theological substance, to the precise geometries of Piero della Francesca, where divine order is rendered mathematically visible, many artists of the 15th and 16th centuries sought to make the invisible real. Their canvases were not simply devotional—they were symbolic instruments, reflective surfaces in which mysteries might be contemplated and divine truths distilled.

In the north, Jan van Eyck wove alchemical themes into his sacred tableaux with painstaking clarity. His Ghent Altarpiece is not merely a polyptych of saints and angels—it is a vision of sacramental transmutation, in which the Lamb of God bleeds into a chalice at the centre of a vast celestial liturgy. The central panel becomes an alchemical altar: blood, wine, and light converging in an act of divine refinement. Even his secular works, such as The Arnolfini Portrait, are rich in encoded symbols of fertility, transformation, and spiritual contract.

Even Leonardo da Vinci, though more philosophical than overtly devotional in his private writings, wove transformational symbolism into his sacred compositions with extraordinary subtlety. In works like the Virgin of the Rocks, the holy figures are enveloped in a dark, mineral grotto—not merely a landscape, but a womb of the earth, suggestive of pre-creation and the alchemical prima materia. The figures emerge from this shadowy matrix not as static icons but as living forms in the process of revelation. The cave itself functions as a sacred vessel, an alchemical crucible in which divine presence takes shape.

Leonardo’s art, while fully within the Roman Catholic tradition, often presents spiritual mystery not in didactic clarity but in layered suggestion—turning nature into metaphor, light into metaphysics, and form into symbol. His Christ child, like Lippi’s, becomes more than a figure of devotion: he is the radiant tincture, the visible Word, the philosopher’s gold taking flesh in the chamber of the world. For more on Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks, see our article, Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother? Dual Messiahs.

Yet among all these masters, Lippi stands apart for one potent inclusion: the glass vessel, subtly present in his Annunciation scenes. This object, fragile and luminous, bears a striking resemblance to the pelican flask used in alchemical distillation—a vessel through which the substance is heated, circulated, broken down, and spiritually refined. In the language of the Magnum Opus, it signifies the process of death and resurrection, separation and unification. By placing such a vessel beside the Virgin Mary—a woman the Church venerates as vas spirituale, vas honorabile, and vas Dei—Lippi performs more than an artistic flourish. He visualises the metaphysical: Mary as the living alembic, and Christ as the Stone, distilled not in laboratory glass but in the sanctified body of the Mother of God.

“Many artists touched the threshold of sacred alchemy. It was Lippi, however, who made the vessel visible”.

Final Reflection: The Alchemy of the Eye

“Through the lens of Alchemy in Christian Art, sacred vision itself becomes transmutative — the eye purified not by gold, but by contemplation and grace.”

Filippo Lippi’s religious works offer more than narrative. They are visual sacraments, constructed with the symbolic grammar of Roman Catholic theology and enriched by the esoteric currents of his time. From the water-filled vessel of the Annunciazione Martelli to the stone-lying child of the Adorations, he charts the journey of spirit into form, and invites the viewer to trace it inward.

But this invitation is not merely devotional. It is initiatory. The paintings are not simply seen—they are worked through, like texts, like rites. They are acts of visual alchemy. In their compositional stillness lies the same pattern found in Hermetic diagrams and liturgical calendars: the soul must be prepared, the vessel must be cleansed, and then—only then—may the divine appear. And when it does, it will not speak in thunder but in silence, in image, in stillness, in light refracted through water, through glass, through the gaze.

This is the alchemy of the eye—a transmutation not of base metals but of perception itself. It is what happens when sight becomes contemplative, when form becomes inwardly intelligible, when beauty ceases to flatter and begins to sanctify. In this way, Lippi’s art is not an end, but a mirror: it reflects the process of Incarnation not only in history, but in the soul of the beholder. The eye becomes the vessel, the painting the agent, and the mystery—still unbroken—is the same: that the infinite should clothe itself in matter, that the eternal should touch the visible, and that the viewer, kneeling in vision, should say with Mary: fiat. “Ecce ancilla Domini; fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum.”

In this vision, the eye does more than perceive—it undergoes transmutation. As explored in the section titled, Mary the True Alembic, and Christ Child the Philosopher’s Stone, the sacred image itself functions as a mirror of the alchemical marriage between vessel and substance. Mary is not only the bearer of Christ but the true alembic—the purified glass in which divine spirit is received, sealed, and made manifest. Her womb is the sacred retort, not by nature but by grace, prepared to contain what no other vessel could.

Within her, the Logos undergoes divine distillation, descending invisibly and emerging in visible form. And Christ, born of that clarified matrix, is not simply child—he is the Philosopher’s Stone, the perfected union of heaven and earth, of spirit and matter. To look upon this child in the arms of the Virgin is to behold the Magnum Opus complete: gold not as metal, but as illumined flesh, the divine tincture visible to the alchemised eye.

Just as alchemists use twin pelican flasks to place the unified Mother Tincture—to refine and circulate the volatile and fixed elements of the Great Work—so too the Virgin and her child form a sacred dyad, vessel and essence, matrix and elixir. For those seeking more profound insight into practical alchemy and the philosophy, symbolism, and practice of true Christian alchemy, Templarkey will soon publish an article on the spiritual and material dimensions of the Philosopher’s Stone.

“In that moment, as in the image, the alchemical work is done. Not in gold, not in fire—but in flesh, in stillness, in light”.

Frequently Asked Questions: Alchemy in Christian Art

What is meant by “Alchemy in Christian Art”?

Alchemy in Christian art refers to the symbolic use of alchemical concepts—such as purification, transformation, and the Philosopher’s Stone—within Christian theological contexts. Artists often used visual metaphors like glass vessels, pelican birds, or sacred light to reflect ideas of spiritual regeneration and divine incarnation.

How does Filippo Lippi’s Annunciation symbolise alchemy?

In Lippi’s Annunciation, the inclusion of a transparent glass vessel symbolises the Virgin Mary as the spiritual alembic—pure, sealed, and receptive—through whom divine substance takes form. This mirrors the alchemical process of distillation and embodies the mystery of the Incarnation in visual form.

What is the connection between the pelican and the Eucharist?

In medieval Christian symbolism, the pelican was believed to wound itself to feed its young with its own blood. This image was adopted by the Church as a figure of Christ’s sacrifice in the Eucharist. In alchemical tradition, the pelican flask performs a similar self-circulating function, purifying the contents from within.

Is there a link between alchemy and the Philosopher’s Stone in Christian thought?

Yes. In Christian-alchemical frameworks, the Philosopher’s Stone is often interpreted as Christ Himself—the perfected matter, uniting heaven and earth. The alchemical Magnum Opus and the Incarnation are spiritually analogous: both represent transformation from base to divine through a sacred process of death, resurrection, and renewal.

Why is alchemy used in Christian Renaissance painting?

During the Renaissance, theology, natural philosophy, and art were deeply intertwined. Alchemical imagery was used not to promote magic, but to express Christian mysteries through visual allegory. The painter’s canvas, like the alchemist’s vessel, became a space for manifesting invisible truths.

Bibliography: For Further Reading

Aquinas, Thomas. Adoro Te Devote. In The Aquinas Prayer Book: The Prayers and Hymns of St. Thomas Aquinas. Trans. Robert Anderson and Johann Moser. Manchester: Sophia Institute Press, 2000.

A Eucharistic hymn by Aquinas, rich in mystical imagery. The verse of the “pious pelican” underpins the symbolic link between Christ, sacrifice, and spiritual nourishment, forming the theological basis for the parallel with the alchemical retort.

Boehme, Jacob. The Way to Christ. Trans. Peter Erb. Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1978.

A foundational Christian mystical text which describes the inward transformation of the soul as a divine alchemical operation. Boehme’s thought bridges Lutheran mysticism with Hermetic imagery, particularly the idea of Christ as the true Stone.

Clairvaux, Bernard of. Sermons on the Blessed Virgin Mary. In The Works of Bernard of Clairvaux, Vol. IV. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1976.

Bernard’s Marian sermons explore Mary as the metaphysical vessel of divine grace. His vision of the Virgin’s fiat as a cosmic hinge informs the theological reading of receptivity and Incarnation.

Derrida, Jacques. On the Name. Trans. David Wood et al. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

A philosophical meditation on naming, revelation, and the ineffable. Derrida’s reflection on presence and language underpins the metaphysical subtlety of visual Incarnation and sacred representation.

Ficino, Marsilio. Three Books on Life. Trans. Carol V. Kaske and John R. Clark. Binghamton: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1989.

The central text of Renaissance Christian Neoplatonism. Ficino’s synthesis of Hermetic, Platonic, and Christian ideas provides the metaphysical foundation for Medici patronage and visionary art as spiritual ascent.

Gettings, Fred. The Secret Lore of the Cathedrals: Alchemy and the Esoteric Symbolism of the Gothic. London: Rider, 1987.

A study of alchemical and symbolic motifs in Christian architecture and art. Provides iconographic parallels to the Eucharistic pelican and the glass vessel as both theological and esoteric emblems.

Lippi, Filippo. Annunciazione Martelli. Martelli Chapel, Basilica di San Lorenzo, Florence. c.1440–1445.

Lippi’s painting serves as the visual heart of this study. The presence of the glass vessel and the formal clarity of Gabriel and Mary embody a theological and symbolic meditation on receptivity and Incarnation.

Newman, William R. Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

A leading historian’s study of alchemy as a serious scientific and theological pursuit. Supports the framing of alchemical motifs as intentional allegories for divine transformation, not mere occult flourishes.

Proclus. The Elements of Theology. Trans. E.R. Dodds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963.

A cornerstone of Neoplatonic metaphysics, foundational for understanding the procession of being, the descent into matter, and the return to unity—concepts central to both spiritual alchemy and Christian mysticism.

Ruck, Carl A.P., and Mark Alwin Hoffman. Alchemy and Psychoactive Sacraments in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Oakland: Regent Press, 2021.

This provocative work argues that Renaissance religious art, including Lippi’s, was designed as a visual aid to mystical or altered states of consciousness. It supports the thesis that such paintings functioned as initiatory images.

Saxl, Fritz. Lectures. Warburg Institute, 1957.

Saxl’s pioneering iconographic research traces the survival of ancient symbols into Christian art. His framework validates the cross-fertilisation of classical, mystical, and theological visual languages.

Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind. New York: Ballantine Books, 1991.

A sweeping intellectual history that contextualises the Renaissance as a pivotal moment of synthesis between myth, reason, and mysticism. Frames the spiritual aspiration underlying Lippi’s Florentine milieu.

Templarkey. The Templarkey Magazine: Issue 11, Throne of Wisdom (Sedes Sapientiae), 2024.

Within this issue of the Templarkey Magazine, there are revelatory studies on the so-called Virgins in Majesty and articles on topics such as: Black Madonnas, Theotokos the Virgin Mary as the Mother of God, Throne of Wisdom (Sedes Sapientiae) and, Our Lady of Le Puy and King Louis IX: The Legend of Saint Louis and the Virgin in Majesty Statue.

Walker, D.P. Spiritual and Demonic Magic: From Ficino to Campanella. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2000.

A classic study of esoteric traditions in Renaissance thought, especially the tension between Christian theology and Hermetic mysticism. Supports the claim that artists like Lippi operated within overlapping sacred and esoteric symbolic systems.

Wind, Edgar. Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance. London: Faber & Faber, 1958.

Explores how Renaissance art concealed Neoplatonic and Hermetic philosophies beneath Christian subjects. A seminal reference for interpreting Medici-era art as both doctrinal and esoteric visual theology.