Christmas and Yule: Debunking the Pagan Origins Myth (Sol Invictus & Saturnalia)

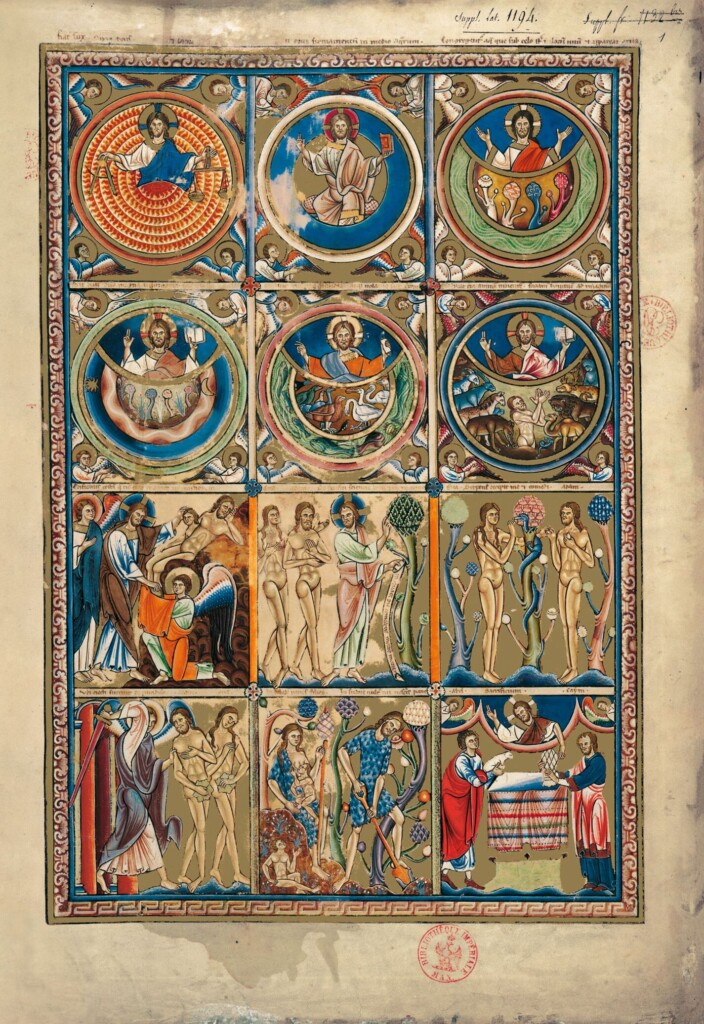

Abstract

This article re-examines claims of the “pagan origins” of Christmas by integrating calendrical history, patristic theology, philology, and reception history. It argues that the emergence of 25 December as the Nativity feast is best explained by Christian computistical reasoning—linking conception and Passion within a theological chronology—rather than by direct derivation from a pre-existing Roman festival of Sol Invictus, Saturnalia, or Germanic Yule.

Particular attention is given to the Chronograph of 354 and its Natalis Invicti entry, which is treated as late evidence for a December observance within the Roman cult of Sol and, on present evidence, insufficient to establish priority over Christian calendrical logic centred on 25 March and its nine-month extension to 25 December. The study then analyses the biblical and philosophical background to Christian “sun” and “light” language (notably Malachi 4:2 and the Johannine Prologue), distinguishing metaphysical and ethical symbolism from cultic identification with the solar deity.

Patristic authors (including Tertullian, Origen, and Leo the Great) are examined as witnesses to late antique anxieties about solar worship and as evidence that Christian tradition policed the boundary between natural symbolism and nature-cult while the December Nativity was being received and articulated in the Latin West. A further section reads Luke’s infancy narrative and later liturgical and mystical interpretations of Christmas as kenosis, New Adam theology, and the sacramental re-reading of cosmic time against imperial “birthday” ideology.

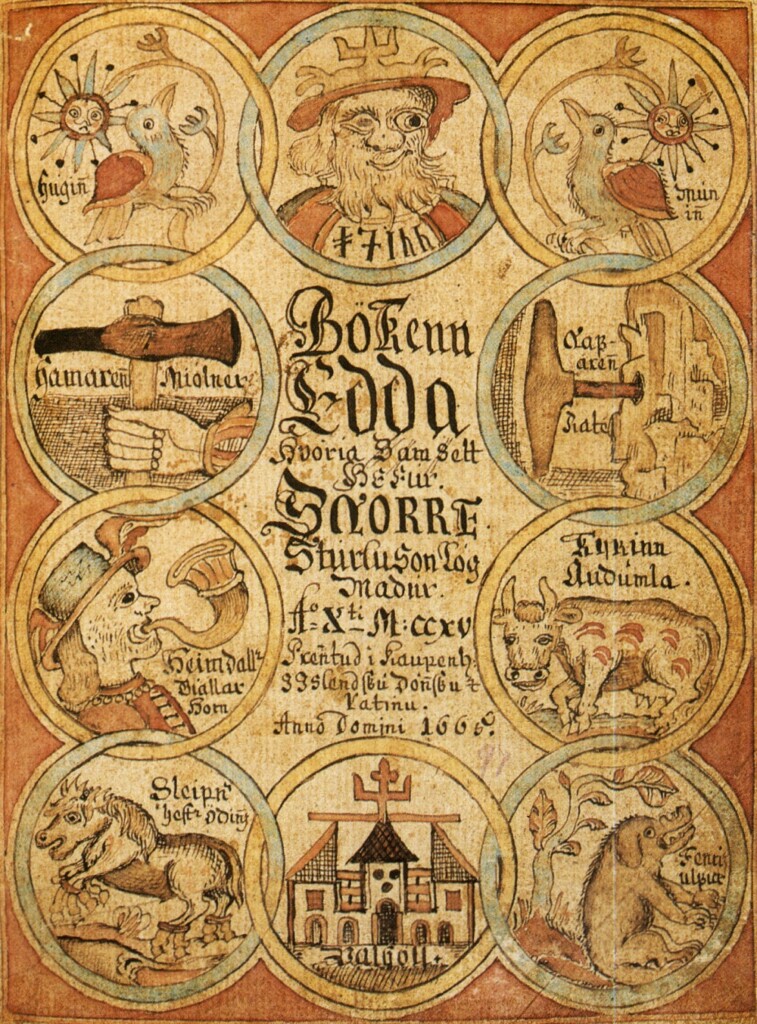

On the northern side, the article reassesses Yule terminology (Giuli/Geola, Jól) and midwinter dating through Bede, the Old English Martyrology, and Scandinavian/Icelandic materials. Drawing on Régis Boyer and related scholarship, it treats saga and Eddic witnesses as late, Christian-mediated compositions shaped by medieval narrative conventions, and therefore as limited evidence for reconstructing a “primordial pagan Yule”.

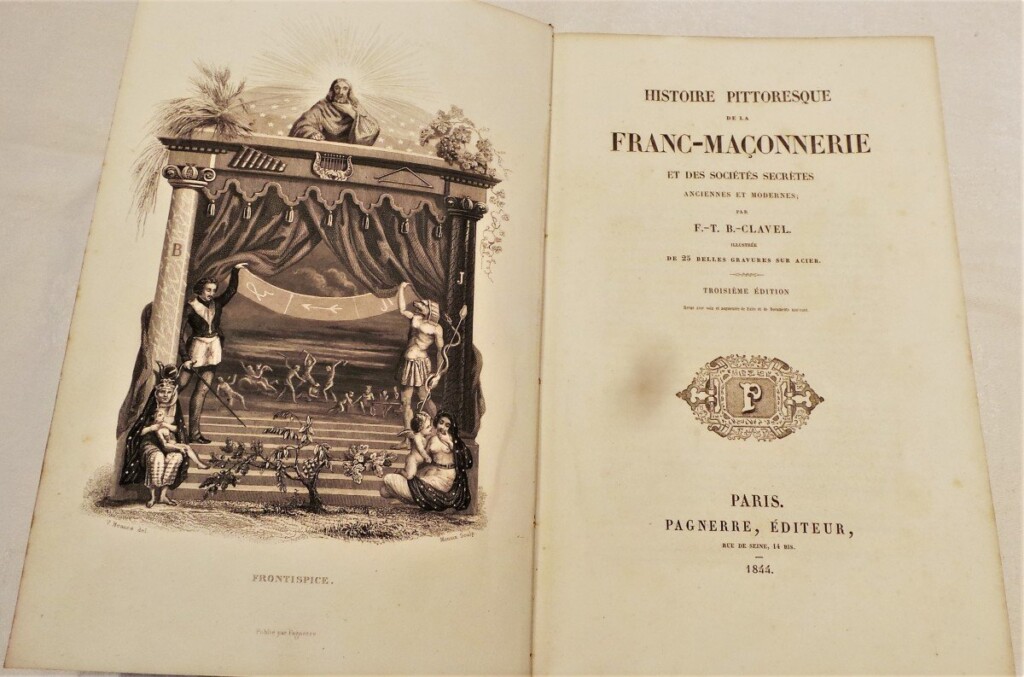

Finally, the article traces the genealogy of solar and zodiacal theories of Christianity from Charles-François Dupuis through nineteenth-century comparative and Masonic historiography to modern mythicism, showing how a rhetorically powerful but evidentially fragile narrative came to eclipse better-attested Christian explanations.

The article’s specific contribution is to delimit, with close textual and calendrical analysis, what the Chronograph of 354 (and its Natalis Invicti entry) can and cannot demonstrate about the priority, scope, and causal relationship between Roman solar observances and the Christian adoption of 25 December.

Introduction: Why Christmas Is Accused of Being Pagan

The “stolen solstice” narrative in modern culture

Christmas, we are often told, is a stolen feast. In newspaper columns, popular history paperbacks, atheist memes, and neo-pagan handbooks, the same story circulates with remarkable confidence: the Church “hijacked” an ancient midwinter festival; 25 December is really the birthday of Sol Invictus, or Mithras, or an “old pagan Yule”; the Nativity is a thin Christian veneer over a solar cult and a cycle of dying-and-rising gods.

The vocabulary varies, but the argumentative structure is stable. Christianity appears as a late and derivative system, opportunistically rebadging the winter solstice; “pagans”, whether Roman, Germanic, “Celtic”, or vaguely “Nordic”, are cast as the original owners of the date and its customs. This “stolen solstice” narrative is not confined to the fringes. It sits comfortably within Enlightenment astral theories (notably Charles-François Dupuis), within nineteenth-century comparative treatments of religion, within some strands of Masonic historiography, and within contemporary mythicist literature that treats Jesus as a solar cypher rather than a historical Jew. See our dedicated articles for more on Celtic Festivals, such as Samhain/Beltane, and the Celtic calendar, as well as Imbolc Traditions and Rituals.

It also underpins a good deal of modern pagan self-presentation: “Yule” is described as one of the oldest winter celebrations in the world, while Christmas is treated as a late Christian overlay. The result is a peculiar coalition: militant secularists, romantic pagans, and some Protestant critics of “unbiblical feasts” all repeat—sometimes for very different reasons—substantially the same story about Christmas, Yule, and the sun.

Method: calendars, texts, archaeology and reception history

The aim of this article is to test that story against the evidence. Rather than beginning from modern polemics, it begins with ancient calendars, texts, and material culture, and then works forward through medieval liturgy and modern reception. Three kinds of evidence are central.

First, calendrical and computistical sources: the Chronograph of 354, the Roman calendrical tradition (including ferial and festival notations), and Christian traditions for dating the Passion, conception, and Nativity.

Second, textual witnesses: patristic sermons and treatises, biblical exegesis, and early medieval Latin and vernacular works such as Bede’s De temporum ratione, the Old English Martyrology, and later Icelandic saga and Eddic materials.

Third, archaeological and historical data: evidence for cultic settings and ritual practice, Scandinavian and Romano-Gallic contexts, and the afterlives of holy wells, midwinter feasting, and rural devotions. The method throughout is historical and reception-oriented. It does not assume that terms such as Yule (Giuli/Geola, Jól) or “Sol Invictus” have a single, unchanging meaning.

Instead, it traces how these labels are attested, how they shift, and how they are reused in new settings: how a fourth-century Roman solar title appears in an imperial almanac; how a Germanic winter name functions, in Christian England, as a way of speaking about the Christmas season; how Icelandic authors, writing centuries after conversion, remember and reshape pre-Christian feasting within clerical and hagiographic narrative conventions. In this strict sense of reception history, many of our sources are not transparent windows into an untouched pagan antiquity, but Christian-period testimonies that already interpret what they describe.

Definitions and scope: “pagan”, “origin”, “continuity”, “syncretism”, “custom”

Because the key terms of the debate are themselves unstable, a few definitions are necessary at the outset. By “pagan”, this article means concrete historical religious systems—Roman civic cults, solar cults of the late empire, and Germanic ritual complexes—rather than a timeless, undifferentiated “nature religion”. “Origin” is used in a strict chronological sense: when a given date, feast, or custom is first attested, and in what milieu.

“Continuity” refers to demonstrable persistence or adaptation of practices across religious change; it must be argued from evidence, not presumed from superficial similarity. “Syncretism” denotes deliberate fusion or mutual reinterpretation between traditions, rather than mere coexistence in time. Finally, “custom” must be distinguished from “cult”. Gift-giving, feasting, decorating with greenery, lighting fires, and eating pork can occur in many settings with different meanings.

When the question is whether a custom is “pagan” or “Christian”, the issue is not whether it is old or widespread, but whether it can be situated within a specific ritual system and theology. One guiding contention of this study is that parallels are easy to assemble; provenance is difficult to establish. Much that is confidently labelled “pagan Yule” or “solar Christmas” proves, on inspection, to be medieval Christian practice, early modern invention, or nineteenth-century romantic projection. Against the prevailing “stolen solstice” narrative, this article advances three theses.

First, that 25 December as the date of the Nativity is most plausibly explained by Christian computus and theological reflection (Passion, conception, creation) and is not demonstrably derived from a prior Roman solar feast on that day.

Second, that Christian “sun” and “light” language—Malachi’s “Sun of Righteousness”, the Johannine Prologue, and patristic preaching—functions within a metaphysical and Christological register rather than as an adoption of solar cult.

Third, that Yule, whether in Anglo-Saxon England or the Nordic world, is encountered in our sources in Christian contexts, and that the modern picture of a primordial, self-contained pagan Yule owes more to late medieval literature and modern myth-making than to early medieval evidence.

The Roman Calendar and the Making of 25 December

Sol Indiges, Sol Invictus and the Roman cult of the sun

Roman religion never lacked solar language, but the status and political weight of Sol shift over time. Early Roman usage includes Sol Indiges, whereas Sol Invictus becomes conspicuous in later imperial discourse; modern scholarship has repeatedly warned against treating “Sol Invictus” as a wholly new, imported deity with an automatically “solstitial” festival attached to him.¹ What matters for the Christmas debate is therefore not the ubiquity of solar symbolism in antiquity, but the narrower evidential question: when and where a fixed civic observance on 25 December is actually attested.²

A recurrent modern simplification equates “25 December” with “the winter solstice” and assumes a long-standing solstitial birthday of Sol. The evidential posture of this article is stricter. “Solstitial” here denotes late-December cosmic symbolism and calendrical rhetoric in late antique discourse, not a precise astronomical claim; the argument proceeds from what the documentary record can securely support.³

Saturnalia, Bruma and Brumalia: dates and meanings

Saturnalia is Rome’s best-known mid-December festival, celebrated over several days and characterised in both ancient description and modern synthesis by feasting, role-play and inversion, and gift exchange—features that make it an obvious point of comparison in later popular accounts of Christmas. Yet Saturnalia does not itself constitute a “birth” feast on 25 December, and similarity of seasonal conviviality is not evidence of calendrical priority or causal derivation.⁴

The terms bruma and brumalia are often invoked as though they name an early, fixed Roman solstice festival that “explains” Christmas. The evidence is more uneven. Bruma can function as seasonal vocabulary (“shortest day”/winter), whereas Brumalia is discussed more securely in later sources and contexts; its reconstruction as a decisive, early Roman festival with a fixed date is therefore difficult to establish with confidence.⁵ For that reason, Bruma/Brumalia are best handled as part of a broader winter lexicon and later festival ecology, rather than as a demonstrable predecessor that determines the Christian choice of 25 December.⁶

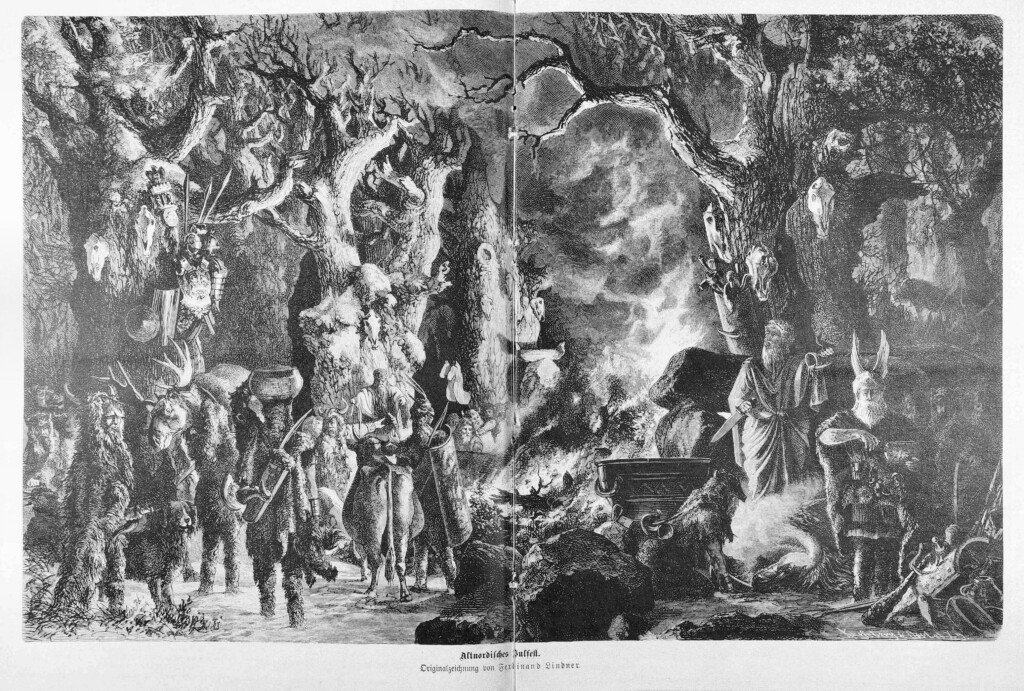

The Chronograph of 354 and the Natalis Invicti

The decisive Roman calendrical witness is the Chronograph of 354 (the so-called Calendar of Filocalus), a late Roman dossier that preserves both civic and Christian materials and provides a mid-fourth-century Roman snapshot of “urban time”.⁷ Within the civil calendar appears the entry for 25 December: “N[atalis] Invicti C[ircenses] M[issus] XXX” (“Birthday of Invictus, 30 chariot races”). This establishes, at minimum, that an Invictus celebration with games was calendrically noted at Rome on 25 December in the fourth century.

Methodologically, however, the Chronograph must be handled with precision. A calendar entry is strong evidence for attestation, but weak evidence for origin or causation. It does not, by itself, prove that the observance began under Aurelian, that it was empire-wide, or that it determined Christian practice. Indeed, the same dossier also transmits a Christian register headed by the Nativity of Christ on 25 December, and careful scholarship stresses that—on the Chronograph alone—the direction of influence between “Invictus” and Christmas cannot be established.⁸

Aurelian (AD 274) and the politics of Sol: what the evidence warrants

Aurelian’s reign remains crucial for understanding the political elevation of Sol in the late empire. In the context of third-century crisis and restoration, solar idiom could serve as an imperial language of victory and unity, and Aurelian’s programme is plausibly part of the wider conditions that make solar titulature and imagery increasingly resonant in the later third and fourth centuries.⁹

Yet the common claim that Aurelian instituted—or fixed on 25 December—a festival of Sol is precisely the sort of inference that outruns the early evidence. The most explicit, quotable 25 December attestation belongs to the mid-fourth-century Chronograph dossier; moreover, scholarship emphasises that the festivals securely associated with Sol in other evidence do not straightforwardly converge on the winter solstice.¹⁰

Accordingly, in this article, Aurelian’s solar programme functions as contextual explanation rather than sufficient cause for the Christian date: it helps to explain why solar language is culturally legible, but the rationale for the Nativity on 25 December must be tested primarily within Christian chronography and theology (computus), which is the subject of the next section.¹¹

Constantine and the Solar Vocabulary of Empire: Subordination, not Syncretism

Constantine’s reign adds a further, often misunderstood, layer to this solar–political landscape. Still operating within a Roman symbolic world in which Sol functioned as a widely legible emblem of imperial favour, he continued to deploy solar imagery in public representation (not least on coinage) even as his policies increasingly favoured Christianity. Yet Eusebius’ famous account of Constantine’s pre-Milvian vision explicitly reorders the hierarchy: the sign of the cross appears “above the sun”, signalling—within Eusebius’ narrative—not fusion with astral power but the subordination of the visible luminary to the victorious Christ.

The same logic helps to read Constantine’s Sunday legislation of AD 321. The law orders rest for judges, urban populations, and workshops on the “venerable day of the sun” (venerabili die solis), while explicitly allowing agricultural labour to continue when weather and seasonal necessity require it. This is best read as the retention of inherited civic nomenclature for the first day of the seven-day week, rather than the institution of a new solar feast ex nihilo. Christian communities had long assembled on Sunday, the day of the Resurrection, and early Christian writers already interpreted this practice christologically while rebutting accusations of heliolatry. Constantine’s measure, therefore, aligns the juridical rhythm of the empire with an already established Christian day of gathering, while leaving conventional Roman terminology in place for administrative intelligibility.

What Constantine does not provide is a solar cultic foundation for Christmas. Neither his laws nor his religious symbolism supplies an “origin” for 25 December as the Nativity feast; that question turns on earlier Christian chronography and computistical theology (conception/Passion dating and the nine-month interval), and on what the Chronograph of 354 can and cannot establish about fourth-century Roman attestation.

- Steven Hijmans, “Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas,” Mouseion 3rd series 3 (2003): 377–398, at 381–383.

- C. P. E. Nothaft, “The Origins of the Christmas Date: Some Recent Trends in Historical Research,” Church History 81, no. 4 (2012): 903–911, at 906–907.

- Nothaft, “Origins,” 904 (on the solstice as a constructed calendrical hinge within Calculation Theory style reasoning); cf. Hijmans, “Sol Invictus,” 395–397 (on separating solstice symbolism from pagan solar cult influence).

- Gary Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History (London: Routledge, 2012), section on Saturnalia; Fritz Graf, Roman Festivals in the Greek East from the Early Empire to the Middle Byzantine Era (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), relevant discussion of winter festival complexes.

- Graf, Roman Festivals, discussion of Brumalia/Bruma terminology and later attestations.

- Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion, discussion of late-December festival vocabulary.

- Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), esp. analysis of the calendar dossier.

- Nothaft, “Origins,” 906–907 (quoting the entry “N[atalis] Invicti C[ircenses] M[issus] XXX”).

- Gaston H. Halsberghe, The Cult of Sol Invictus (Leiden: Brill, 1972), on Aurelianic institutional promotion; Alaric Watson, Aurelian and the Third Century (London: Routledge, 1999), on the political theology of restoration; Hijmans, “Sol Invictus,” 377–380 (framing of the modern construct problem).

- Nothaft, “Origins,” 906–907; Hijmans, “Sol Invictus,” 395–397.

- Nothaft, “Origins,” 904, 906–907 (on the limits of HRT and the need to integrate Christian chronological thought).

How Early Christians Dated the Nativity

Computus and integral time: how Christians synchronised salvation history

The attempt to date the Nativity belongs to a broader culture of computus (sacred calendrical reckoning), in which Christians sought to relate the events of Christ’s life to one another in a coherent chronology of salvation. In this framework, dates function not merely as archival “facts” but as theological coordinates: the Passion, the conception, and the birth are treated as mutually illuminating moments within an ordered divine economy. Early Christian chronological speculation, therefore, tends to work by establishing anchor-dates (especially for the Passion) and then reasoning outward by typology and numerical symmetry, rather than by claiming independent access to a historical birth certificate.¹

From Passover to Annunciation: 25 March as axis of salvation history

A key move in the “calculation theory” tradition is the alignment of Christ’s conception with the date assigned to the Passion, producing a deliberate parallelism between incarnation and redemptive death. In its standard form, this reasoning fixes the incarnation (Annunciation/conception) on 25 March and then reaches 25 December by adding a schematic nine months.

This logic is explicitly attested in Augustine, who reports the belief that Christ was conceived on the same day of the year as his Passion, with birth nine months later.² The point is not that the equinox caused the Christian date, but that Christian chronologists found 25 March a fitting hinge for integral time: creation, incarnation, and redemption could be narrated as a harmonised temporal pattern.³

Hippolytus, Julius Africanus, Augustine, and the “calculation theory”

The early evidence is complex and must be handled without overstatement. Hippolytus is central because his surviving material (notably the Paschal computations associated with him and the later transmission of the Chronicon) shows precisely the sort of chronological reasoning that could yield a midwinter Nativity by internal Christian logic. Recent analysis argues that, given Hippolytus’ synchronisms (not least his handling of “years… and months” between creation and Christ), a birth “sometime around December 25” is a plausible implication of his system—though the conclusion depends on how one reconstructs the work and its assumptions.⁴

For Julius Africanus, the argument is not that he explicitly instituted a Christmas feast, but that his chronology already operates with the creation–incarnation framework and millennial totals that make a 25 December reckoning intelligible within Christian scholarship of the early third century.⁵ Augustine is then an important witness to the logic (conception and Passion on the same calendar day; birth nine months later), showing how such chronological-theological symmetry became readily speakable within the Latin tradition.²

The emergence of 25 December in the Latin West and 6 January in the Christian East

As a liturgical feast, Christmas emerges into clear view in the fourth century; its later prominence should not be read back as if it were universally “obvious” from the start. The “calculation theory” helps explain why late antique Christians could find the winter solstice an attractive terminus for a Nativity date without presupposing a simple act of pagan borrowing.⁶

In parallel, many Eastern communities associated the Nativity with 6 January (within the wider complex of Epiphany/Theophany), and calculation-based explanations have likewise been proposed for that date by reference to a Passion date on 6 April.⁷ The divergence therefore reflects not a single origin-story but multiple regional trajectories in which chronology, biblical exegesis, and developing liturgical practice interact.

Dionysius Exiguus (Denys le Petit), a learned monk from Scythia Minor (modern Romania) active in Rome from the late fifth to mid-sixth century, was commissioned by Pope John I to address the “Paschal controversies” by refining the rules for dating Easter and bridging Jewish lunar reckoning with the Roman solar calendar. In his Paschal computus (525), Dionysius proposed a major shift in Western timekeeping: years should be counted from the birth of Christ rather than from the founding of Rome, placing the Nativity at 25 December 753 ab urbe condita and effectively making it the start of “Year 1”.

Later historians have judged his chronology slightly off—since Jesus’ birth is linked to Herod’s reign and Herod died before the proposed date—and the absence of a year zero in Western reckoning further complicates the count, so Jesus’ birth is often placed a few years “before AD 1” (roughly 3–6 BC), a point even noted by Benedict XVI. Dionysius’ system also took time to spread across Western Europe and interacted unevenly with Julian and Gregorian conventions; notably, the papacy only standardised the civil new year on 1 January (a few days after Christmas) in 1622.

- C. P. E. Nothaft, ‘The Origins of the Christmas Date: Some Recent Trends in Historical Research’, Church History 81, no. 4 (2012), pp. 904–905 (summary of “Calculation Theory” as deriving 25 December from Passion/conception reasoning).

- Augustine, De Trinitate [On the Trinity], IV.5.9, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series I, vol. 3 (ed. Philip Schaff) (statement of the belief that conception and Passion fall on the same day of the year, with birth nine months later).

- C. P. E. Nothaft, ‘Early Christian Chronology and the Origins of the Christmas Date: In Defence of the “Calculation Theory”’, Questions Liturgiques/Studies in Liturgy 94 (2013), p. 249 (articulation of the Calculation Theory logic: crucifixion assigned to 25 March; incarnation on 25 March; birth on 25 December by nine-month count).

- Thomas C. Schmidt, ‘Calculating December 25 as the Birth of Jesus’, Vigiliae Christianae 69 (2015), pp. 552 (on the Chronicon and transmission problems), 557 (reconstruction implying birth “sometime around December 25”, conditional on assumptions).

- Nothaft, ‘Early Christian Chronology’, pp. 263–264 (Africanus’ AM chronology; creation–incarnation framework relevant to early Christian chronological reasoning).

- Nothaft, ‘Early Christian Chronology’, pp. 249–250 (CT as a supplementary explanation; also notes the weakness of the claim that Aurelian instituted a fixed 25 December Natalis Invicti in 274).

- Nothaft, ‘The Origins of the Christmas Date’ (2012), p. 904 n. 4 (summary of the parallel explanation offered for 6 January from a Passion date on 6 April; with reference to Talley).

Christ as Light, Not Sun-God: Biblical and Philosophical Foundations

Malachi’s “Sun of Righteousness” and the Prologue of John

Malachi’s promise, “for you who fear my name, the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings” (Mal 4:2; Heb. 3:20), becomes a principal scriptural anchor for later Christian “solar” language.¹ The image is already ethical and covenantal, not cultic or astronomical: the “sun” is qualified by righteousness (Heb. ṣĕdāqāh; LXX δικαιοσύνη), and functions within a context of judgement and vindication rather than astral devotion.²

John’s Prologue intensifies the prophetic register by shifting from “sun” to “light” and by placing that light “in the beginning” with God. “In him was life, and the life was the light (φῶς) of human beings. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it” (Jn 1:4–5).³ John does not identify Christ with the sun (ἥλιος), but with light, life, and the pre-existent Logos through whom “all things were made” (Jn 1:1–3).⁴ Later, Jesus’ self-identification—“I am the light of the world” (Jn 8:12)—is explicitly revelatory and soteriological: the light is the divine presence given to the world, not a deified luminary.⁵

In John’s Prologue, “light” is not the physical sun but the primordial Fiat Lux—the uncreated divine radiance present “in the beginning” with God, through whom creation comes to be. Christ is therefore identified with the pre-existent Logos as the source of life and intelligibility, a revelatory light that enters darkness to save, rather than a luminary to be venerated.

When the Fathers pair Malachi with John—speaking, for example, of sol iustitiae and confessing Christ as “Light from Light”—they are not sliding into heliolatry but interpreting prophetic metaphor within a metaphysical framework that sharply distinguishes Creator from creature.⁶ As a representative Latin witness, Augustine can exploit “sun/light” imagery precisely to confess Christ’s saving illumination, not to blur the line between God and the created luminary.⁷

Platonic Justice, the Idea of the Good, and Christian “sun” language

In Republic VI, Plato’s “sun analogy” (507b–509c) distinguishes the visible sun from the intelligible Good: the sun is an image within the visible order, whereas the Good grounds intelligibility and being in the intelligible order.⁸ Justice (δικαιοσύνη) is treated as the ordering virtue of soul and city rather than as any physical phenomenon.⁹ The Divided Line (509d–511e) and the Cave (514a–521b) reinforce the same hierarchy: ascent is an ascent beyond images to intelligible reality.¹⁰

In that philosophical horizon, Christian “sun” language is most naturally read as metaphysical and ethical rather than naturalistic: Christ is named as the source of righteousness, intelligibility, and moral order; the physical sun remains a created analogue. The conceptual move is “upward” (from visible to intelligible), not “sideways” into civic solar cult.⁸

Logos, creation, and the distinction between Creator and created luminaries

At the heart of the Christian rejection of sun-cult lies the Creator–creature distinction. Genesis 1 is decisive: light is created before the luminaries. “Let there be light” (Gen 1:3; Vulg. fiat lux) precedes the creation of the “greater” and “lesser” lights on the fourth day (Gen 1:14–18).¹¹

The sequence of Genesis 1 is itself a theological boundary-marker. By narrating light prior to the luminaries—fiat lux before sun and moon—the text refuses any identification between the divine source of illumination and the celestial bodies that later bear light within the created order.¹²

The luminaries are introduced not by divine names but by functional description (“greater” and “lesser” lights), and their task is calendrical and instrumental: to mark times and seasons and to “rule” day and night (Gen 1:14–18).¹³ This ordering becomes a template for Christian metaphysics: God is light by essence; the sun is light by participation and service.

The Johannine Prologue then identifies the pre-existent Logos as the agent of this creation: “All things were made through him” (Jn 1:3).¹⁴ That places the Word on the side of the Creator, and the sun, moon, and stars on the side of created realities. Christian “light” language, therefore, does not identify Christ as one luminary among others, but as the uncreated source by whom created lights exist.¹⁵

Lux / φῶς as analogy: participation without cultic identity

Christian terms for light—lux, lumen, φῶς—are analogical rather than identificatory. They use sensory vocabulary to speak about intelligibility, truth, and divine life: creatures “have” light, but they do not be light by essence.¹⁶

The Nicene confession “Light from Light” is formulated to confess divine generation and consubstantiality, not to locate Christ within the solar sphere.⁶ It belongs to the Church’s metaphysical grammar in the Trinitarian controversies, not to any cosmological re-labelling of a pagan luminary.¹⁷

This analogical structure allows Christianity to appropriate cosmically suggestive imagery—dawn, increasing daylight, eastward prayer—without conceding cultic continuity. The created luminary is not divinised; it is relativised and made to point beyond itself to the Logos in whom justice, truth, and life subsist.¹⁸

- Mal 4:2 (Heb. 3:20).

- Mal 4:1–3 (context of judgement/vindication); cf. Mal 3:16–18.

- Jn 1:4–5.

- Jn 1:1–3; cf. Jn 1:9.

- Jn 8:12; cf. Jn 12:46.

- Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (Constantinople I, 381), “φῶς ἐκ φωτός / lumen de lumine”, in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (eds.), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II, vol. 14, The Seven Ecumenical Councils (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing, 1890), Creed text (Constantinople).

- Augustine, De Trinitate I.2.4 (on Christ as true light illuminating minds), in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series I, vol. 3, ed. Philip Schaff (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing, 1887).

- Plato, Republic 507b–509c.

- Plato, Republic 433a–444e, esp. 441c–444a.

- Plato, Republic 509d–511e; 514a–521b.

- Gen 1:3 (Vulg. fiat lux); Gen 1:14–18.

- Gen 1:3.

- Gen 1:14–18.

- Jn 1:3.

- Jn 1:3–5.

- Jn 1:9 (the “true light”).

- Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series II, vol. 14, context of creed in the conciliar material (Constantinople I, 381).

- Gen 1:14–18; Jn 1:3–5.

Patristic Rejection of Solar Worship

Tertullian, Origen and accusations of sun-worship

Already in the second and third centuries, Christian writers were aware that certain Christian practices could be misconstrued as heliolatry. Tertullian, writing in Roman North Africa, reports the allegation directly: “Others … suppose that the sun is the god of the Christians,” precisely because Christians pray towards the east and “make Sunday a day of festivity”.¹

He concedes the superficial resemblance but rejects the inference by distinguishing symbol from object: external orientation and civil nomenclature do not determine the identity of worship. The decisive question is the referent of devotion. Christians worship the Creator; the sun is a creature and, at most, one of the “ornaments” of the world.²

Origen addresses the same point with equal clarity in his discussion of prayer. He acknowledges the widespread Christian practice of praying toward the east but rejects the interpretation that such bodily orientation implies worship of the visible luminary. Rather, he treats the east as a theological and eschatological symbol: it signifies the soul’s turning towards the “dawn of the true light” and towards the divine realities to which the created world bears witness.³ In both authors, then, the accusation of sun-worship is neither ignored nor absorbed into syncretism: it is recognised, answered, and explicitly refused at the level of first principles.

Leo the Great and the winter solstice: sermons against confusion with Sol

By the fifth century, the proximity of Christmas to late-December seasonal symbolism and the residual prestige of solar language and gesture at Rome created a real pastoral problem. Leo the Great addresses it with striking specificity. Preaching in Rome, he rebukes those who, after ascending the steps of the basilica of the blessed Apostle Peter, “turn round” and bow “to the rising sun” before entering to worship.⁴ Even if some attempt to rationalise the gesture as honouring the Creator indirectly, Leo treats it as an unacceptable ambiguity. Christians must avoid not only the act but the appearance of sun-worship, because Christian worship is directed to God alone.

Elsewhere in his Nativity preaching Leo makes the doctrinal logic explicit: devotion is not owed to sun, moon, or stars, but to the Creator whose work they are.⁵ The point is crucial for this wider thesis. Leo’s sermons show, first, that late antique Roman Christians could still perform recognisably solar gestures; secondly, that bishops interpreted such acts as incompatible with Christian worship; and thirdly, that Christian “light” rhetoric is framed as anti-heliolatrous in principle, not as a Christianised continuation of solar cult.

Facing East and keeping Sunday: natural symbolism versus solar cult

Two practices most often pressed into “solar Christianity” narratives are (i) facing east in prayer and (ii) keeping Sunday. Patristic sources treat both as symbolically charged, yet categorically distinct from astral worship. Origen’s discussion of direction in prayer is explicit: eastward orientation is interpreted as a bodily sign of the soul’s reorientation towards God and towards the “true light”, not as cult offered to the physical sun.⁶ Tertullian likewise can acknowledge that outsiders infer sun-worship from eastward prayer and Sunday observance, while insisting that resemblance of external practice does not establish identity of cult.⁷

The underlying structure is consistent: the created order—sunrise, direction, the weekly cycle—can be read as meaningful, but it cannot be adored. Natural realities function as signs that point beyond themselves; the object of worship is the divine reality to which they refer. The persistence and sharpness of patristic anti-heliolatry polemic only makes sense on this premise: Christian “light” language and Christian calendrical practice are articulated against solar cult, not derived from it.

- Tertullian, Apologeticum 16, in Ante-Nicene Fathers (ANF), vol. 3: Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian, trans. S. Thelwall, ed. Allan Menzies (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1885), p. 31 (PDF p. 91).

- Tertullian, Apologeticum 16 (ANF 3), p. 31 (PDF p. 91).

- Origen, On Prayer (De Oratione) 20, in CCEL text, pp. 72–73 (PDF p. 75): eastward prayer as sign of “the dawn of the true light”, explicitly rejecting cultic identification with the sun.

- Leo the Great, Sermon 27 (“On the Feast of the Nativity VII”) 4, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (NPNF), Series II, vol. 12: S. Leo the Great; S. Gregory the Great (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing, 1895), p. 388 (PDF p. 410).

- Leo the Great, Sermon 22 (“On the Feast of the Nativity II”) 6, in NPNF II, vol. 12, pp. 347–348 (PDF pagination varies by file).

- Origen, On Prayer 20 (as in n. 3).

- Tertullian, Ad Nationes I.13, in ANF 3, p. 123 (PDF p. 237).

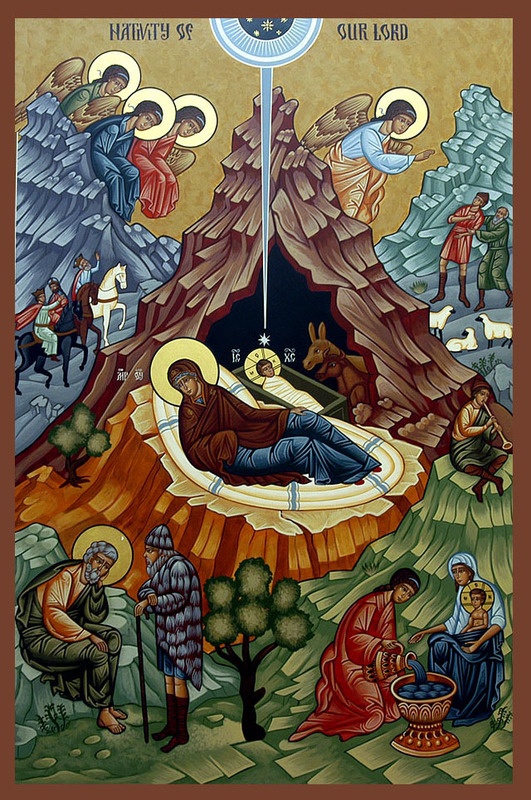

The Theological Meaning of Christmas in Christian Tradition

Kenosis and the “mystique of Christmas time” (Guéranger, Clément, etc.)

In the classic Latin and Eastern traditions, Christmas is not primarily a calendrical problem but a mystery of kenosis: the self-emptying of the eternal Son. Paul’s hymn in Philippians is the governing text: “Though he was in the form of God, he did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself (ἐκένωσεν), taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men” (Phil 2:6–7).¹

Both Olivier Clément and Dom Guéranger read the season of Christmas through this lens. Clément insists that the scandal of Christmas is not sentimentality, but the descent of the Son into vulnerability: the eternal Word enters history as a defenceless child and embraces poverty, marginality, and exile from the beginning.²

Luke’s narrative supports this theological realism: the Child is born under an imperial census, with no place in the lodging, and is soon driven into flight (Lk 2:1–7; Mt 2:13–15).³ Guéranger’s Mystique du temps de Noël develops the same logic by embedding kenosis in liturgical time. The Incarnation, “the Word became flesh” (Jn 1:14), is the axis where divine eternity and human temporality are united in the one Person of the Word.⁴

Within this framework, Guéranger explicitly notes the providential coincidence between late-December cosmic symbolism and the economy of salvation: Christ is born when the night of idolatry has reached its deepest darkness, and the physical light begins to return—yet the true Light appears under the form of weakness.⁵ The “mystique of Christmas time” is therefore the paradox of a glory that hides itself in humility: cosmic imagery may be admitted as symbol, but it is always subordinated to the christological core confessed by the Church.

Against modern reinventions of Yule or consumerist “winter holidays”, both authors insist that Christmas is not a feast of nature or of vague “light” but of the concrete Person who empties himself into history.² If there is a “cosmic” dimension, it functions only as a sign within providence: the eternal Word truly becomes flesh, and that flesh is truly poor.⁴

The New Adam, Bethlehem and the Bread of Life

The Nativity liturgy also reads Christmas through the Pauline typology of Adam and Christ. In Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15, Christ is the “new Adam” who reverses the disobedience of the first; “for as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Cor 15:22).⁶ For Guéranger, the Incarnation is already the beginning of this reversal: the humanity assumed in Mary’s womb and born at Bethlehem is the same humanity that will be offered on the Cross and communicated in the Eucharist.⁷ Christmas is thus not an isolated tableau of infancy, but the first act of the Paschal mystery.

Here, the toponymy of Bethlehem becomes theological: Beth-lehem, “house of bread,” is read as fitting the One who will identify himself as the bread of life and the living bread come down from heaven (Jn 6:35, 51).⁸ In this liturgical reading, the Child laid in a manger already signifies sacramental feeding: the crib gestures towards the altar; the manger towards the Eucharistic gift by which Christ communicates his life.⁹ The season is saturated with the theme of transformative indwelling—“it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20)—and of divinising exchange, “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4).¹⁰

Poverty, peace and the inversion of imperial “birthdays”

Against the background of Roman dies natales, the theological meaning of Christmas is further clarified. In Roman civic and imperial culture, birthdays and foundation days could function as public rituals of patronage, loyalty, and power; the natalis of emperors and cult foundations belonged to the symbolic grammar of legitimacy and prestige.¹¹ The Chronograph of 354 is therefore suggestive, not because it proves causation, but because it juxtaposes within one mid-fourth-century dossier the notation of Natalis Invicti and, in a different register, natus Christus in Betleem Iudaeae.¹² The “birth” Christianity proclaims is not the ascent of power but the descent of the Creator into creaturely poverty.

The Gospels deliberately undercut imperial expectations. Luke begins with Caesar Augustus and the machinery of enrolment, only to move to a marginal couple, a makeshift birth, and shepherds at work in the night (Lk 2:1–20).³ Where imperial birthdays are celebrated with public spectacle, Luke gives angels announcing peace and a sign of powerlessness: a child wrapped in swaddling cloths (Lk 2:12–14).¹³ Where empire marks the consolidation of rule, the Church proclaims kenotic inversion: the eternal Son is “counted” in a census as a subject without status.¹

Clément presses the same contrast against modern distortions of Christmas: the feast is not a “golden calf” of consumption, but a revelation of God’s solidarity with the poor, calling Christians to a corresponding love that participates in Christ’s own self-emptying.² Likewise, the “peace” of Christmas is not a political truce or a sanctification of imperial order, but the peace announced by heaven and bound to the Kingdom that has no end (Lk 2:14; Is 9:6–7).¹³

In this light, Christmas is best understood not as a Christianised solstice or a baptised sun-feast, but as a theological inversion of both nature-cults and imperial cult. The date may sit near a hinge of the solar year, and the liturgy may play with the imagery of returning light; yet the content is irreducibly christological: the lowly birth of the New Adam, in the “house of bread”, for the life of the world, redefines what “birthday”, “light”, “peace”, and even “feast” mean in a Christian key.⁶

- Phil 2:6–7.

- Olivier Clément, Le Dieu vivant. Catéchisme du christianisme orthodoxe (Paris: Stock, 1989), section on the Incarnation/Christmas/kenosis.

- Lk 2:1–7; Mt 2:13–15.

- Jn 1:14; cf. Phil 2:6–8.

- Dom Prosper Guéranger, L’Année liturgique, Le Temps de Noël, vol. I, chap. II, “Mystique du Temps de Noël” (editions vary); see esp. the opening paragraph beginning “Jésus-Christ, notre Sauveur … est né au moment où la nuit de l’idolâtrie …”.

- Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:22, 45.

- Guéranger, L’Année liturgique, Le Temps de Noël, vol. I, chap. II (“Mystique du Temps de Noël”), on the unity of the economy (Incarnation ordered to Pascha and sacramental life).

- Jn 6:35, 51; cf. Beth-lehem (“house of bread”) as a traditional etymology used in Christian preaching.

- Guéranger, L’Année liturgique, Le Temps de Noël, “Le Saint Jour de Noël” (or the Nativity offices), where crib/altar and manger/Eucharist typology is developed in the liturgical commentary.

- Gal 2:20; 2 Pet 1:4.

- Kathryn Argetsinger, “Birthday Rituals: Friends and Patrons in Roman Poetry and Cult,” Classical Antiquity 11, no. 2 (1992): 175–193; cf. Stefan Weinstock, Divus Julius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), on civic sacralisation and the imperial cult calendar.

- Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), Part VI (the calendar) and the Christian list: N INVICTI CM XXX / natus Christus in Betleem Iudaeae.

- Lk 2:12–14; Is 9:6–7.

Yule in the Early Medieval Evidence

Evidentiary tiers and dating controls: contemporaneous sources versus later memory

When we talk about “Yule” (jól / geola / Giuli), we are not dealing with a single, clearly bounded pre-Christian institution but with a patchy dossier of sources, written in different places, centuries apart, and very often in Christian settings. Methodologically, these witnesses cannot all be treated as equal.

At the top tier stand roughly contemporaneous, technical texts that describe time-reckoning or liturgical practice for their own age: Bede’s De temporum ratione (early eighth century), the Gothic calendar fragment, and the Old English Martyrology (ninth century).¹ These give us vocabulary (Giuli / geola / jiuleis), some calendrical alignments, and occasional notices about “heathen” practice, but always filtered through Christian categories and a Christian didactic purpose.²

A second tier consists of later narrative sources, often in Old Norse, composed in the twelfth–thirteenth centuries by Christian, frequently clerically educated, authors. They may preserve genuine traditions about pre-Christian customs, but they are also shaped by hagiographical models and providential historiography. They are, therefore, evidence for how the Christian Middle Ages remembered “Yule”, not transparent windows into an untouched pagan past (Boyer).³

Finally, there is modern reconstruction—philological, archaeological, and folkloric—which attempts to synthesise these layers. Here, dating control is crucial. Any claim that Yule “predates Christianity”, or that it determined the Christian Nativity date, must be tested against the hard fact that our earliest attestations of “Yule” vocabulary occur in Christian contexts and already appear intertwined with Christian calendrical logic.⁴

Giuli / Geola in Bede’s De temporum ratione

Bede’s De temporum ratione (c. 725) is the earliest detailed witness for an English “Yule” vocabulary. In his account of Anglo-Saxon month names, he states that both December and January were called Giuli. This shows that Giuli functions primarily as a winter two-month block in an older lunisolar scheme, not as the name of a single solstitial feast-day.⁵

Bede then adds a crucial alignment: the English “began the year” on VIII Kalendas Ianuarias (25 December), explicitly glossing the date as that “when we celebrate the Nativity of the Lord”. On that same night, he reports a pre-Christian observance, Modranicht (“Mothers’ Night”), so called from the ceremonies performed throughout the night.⁶ Two limits follow from this. First, Bede’s “Yule” terminology is seasonal rather than festival-specific.

Secondly, even when he places a “heathen” observance at the 25 December hinge, he does not name it Giuli, and his explanation is given from within a Christian account of the calendar.⁵–⁶ Bede is therefore strong evidence for vocabulary and for a Christian-era alignment of the year’s turning with 25 December, but not for an autonomous pagan “Yule feast on the solstice” functioning as the origin of Christmas.

The Gothic fruma jiuleis and the jiuleis / jubilee debate

The Gothic evidence, often invoked in modern popular claims, is even more fragile. A Gothic calendar of saints’ days contains the phrase fruma jiuleis, frequently translated “the beginning of Yule”. Whatever jiuleis means, the framework is explicitly Christian and computistical: it occurs inside a Christian calendar dossier, not inside a pagan almanac.⁷

On the word itself, scholarship is divided. Landau has argued that the form presents serious difficulties for derivation from a Germanic “Yule” root and proposes an alternative connection with Latin jubilaeus (“jubilee”), which suits the Christian character of the document more naturally.⁷ Either way, the methodological point remains: the source is too ambiguous and too securely embedded in Christian time-reckoning to sustain claims about a primordial pagan Yule that determines the Christian Nativity date.

The Old English Martyrology and the “first day of Yule”

The Old English Martyrology takes us a step further in the Christian domestication of Yule-language. In its entry for 25 December, it integrates vernacular “Yule” terminology into a Christian martyrological framework organised around the Nativity and the saints, treating the day as the opening of the year and the beginning of Christmas/Yule within a Christian liturgical horizon.⁸ Here, “Yule” is not presented as a free-standing pagan solstice rite. It is Christian calendar-language expressed in inherited Germanic winter vocabulary, now anchored explicitly to 25 December.

Taken together, Bede, the Gothic calendar dossier, and the Old English Martyrology show that our earliest “Yule” evidence is Christian, liturgical, and already synchronised to 25 December as Natale Domini. They do not document an autonomous pagan solstice festival from which Christmas was later copied; they point instead to a palimpsest in which Christmas-tide is expressed in inherited winter vocabulary, with older seasonal customs gradually reinterpreted within Christian time reckoning.⁴ This integration is already explicit in the Old English Martyrology’s treatment of 25 December as the opening of the year and the “first Yule-day” within a Christian martyrological frame.⁸

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15; and The Old English Martyrology (see n. 8), as early medieval witnesses for Anglo-Saxon winter vocabulary and calendrical framing.

- David Landau, “The Source of the Gothic Month Name jiuleis and its Cognates,” Namenkundliche Informationen 95–96 (2009): 239–248 (Gothic calendar context; linguistic issues).

- Régis Boyer, Le Christ des barbares. Le monde nordique (IXe–XIIIe siècle) (Paris: Cerf, 1995), on Christian authorship and the shaping of pre-Christian memory.

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15; Landau, “jiuleis,” 239–248; and Christine Rauer (ed. and trans.), The Old English Martyrology: Edition, Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), entry for 25 December, taken together as the earliest attestations and their Christian framing.

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15 (December and January both called Giuli).

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15 (VIII Kal. Ian. as year-beginning; “when we celebrate the Nativity of the Lord”; Modranicht notice).

- Landau, “The Source of the Gothic Month Name jiuleis and its Cognates,” 239–248 (phonological/morphological objections; proposed link with Latin jubilaeus).

- Christine Rauer (ed. and trans.), The Old English Martyrology: Edition, Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), entry for 25 December (vernacular Yule-language integrated into Christian martyrology).

Anglo-Saxon lunar months and the problem of “midwinter”

The Anglo-Saxon evidence forces us to separate three things that modern writers often flatten together: a winter season, a specific “midwinter” day, and later Christian Christmas. Bede’s De temporum ratione (c. 725) is the key starting point. Explaining the old English month names, he states that the first month, January, is called Giuli, and that December is also called Giuli “by the same name by which January is called”. He adds that “they began the year” on VIII Kalendas Ianuarias (25 December), “when we celebrate the Nativity of the Lord”.¹ In other words, Giuli is not a one-night solstice rite but a two-month midwinter block straddling what we call December and January.¹

Bede also mentions Modranicht (“Mothers’ Night”) on the evening of 25 December, which he reports as a pagan observance, without giving a detailed account of its ceremonies. Crucially, he does not call Modranicht “Yule”: for him, Giuli is a calendrical label for the winter months, not the name of a specific feast.¹ Modern attempts to reconstruct a neat, pre-Christian “Yule on the solstice” therefore rest on fragile ground.

Later Old English usage reinforces the seasonal logic. In the Old English Martyrology, vernacular “Yule” language is already integrated into a Christian martyrological structure anchored on the Nativity, presenting 25 December as the liturgical hinge and speaking of “Yule” in a way that presupposes Christian calendrical framing.² Once a lunisolar system and intercalation are in view, the modern instinct to ask “what exact Julian date was Yule?” becomes anachronistic: seasonal terms float relative to fixed Roman month-days, and Christian usage increasingly stabilises the winter vocabulary around Christmas rather than preserving an independent pagan date.¹–²

King Hákon the Good in Heimskringla: aligning jól with Christian Christmas

For Scandinavia, the most cited narrative locus is Heimskringla (thirteenth century), traditionally associated with Snorri Sturluson. In Hákonar saga góða, Hákon the Good (r. 934–961) is said to have established in law that Yule was to be held “at the same time as is the custom with the Christians”, whereas previously it had been celebrated at “midwinter” and for three nights.³ The passage’s basic logic is clear even if “midwinter” is imprecise in our terms: it imagines an older jól clustered in the dark season, and then a deliberate political-liturgical alignment with the already-established Christian feast.

Methodologically, however, this evidence must be handled as medieval Christian historiography. Boyer is right to stress that Icelandic saga-writing is produced in a Christian culture and shaped by Christian narrative habits and providential reading of the past.⁴ The text can preserve echoes of older practice, but it is also perfectly capable of projecting later Christian calendrical clarity back onto earlier centuries. The safest conclusion is therefore limited: the saga attests a high-medieval memory that jól had once been timed differently and was later synchronised with Christian Christmas; it does not tell us anything about the origin of 25 December within Christianity, which precedes Scandinavian conversion by centuries.³–⁴

Archaeology can add texture to the picture of midwinter observance—feasting, communal drinking, winter slaughter patterns—but it rarely fixes a precise liturgical date. Late Iron Age and Viking Age material culture is consistent with substantial winter gatherings and high-status consumption in the dark season; it is not, by itself, a calendar. A cautious synthesis, even in popular archaeological summaries, is that we can speak confidently of midwinter feasting but only loosely about its timing and even more cautiously about its “theology”.⁵

Set beside the Anglo-Saxon calendrical evidence in Bede and the explicitly Christian framing of “Yule” in later Old English sources, the overall pattern remains stable: “Yule/jól” functions chiefly as winter vocabulary; “midwinter” is a seasonal hinge whose exact date floats across systems; and explicit identifications of jól with “Christmas” belong to post-conversion alignment rather than demonstrating that Christianity borrowed its Nativity date from a Germanic solstice cult.¹–⁵

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15 (December and January as Giuli; year-beginning on VIII Kal. Ian.; Modranicht notice).

- Christine Rauer (ed. and trans.), The Old English Martyrology: Edition, Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), entry for 25 December (vernacular Yule-language integrated into Christian martyrology).

- Alison Finlay and Anthony Faulkes, trans., Heimskringla, vol. 1: The Beginnings to Óláfr Tryggvason (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London, 2011), Hákonar saga góða (passage on aligning Yule with Christian custom; “midwinter” and “three nights”).

- Régis Boyer, Le Christ des barbares. Le monde nordique (IXe–XIIIe siècle) (Paris: Cerf, 1995), on saga authorship, Christian formation, and the shaping of pre-Christian memory.

- “From Jól to Yule,” Scandinavian Archaeology (online article; used with caution), on archaeological limits for dating and interpreting midwinter observance.

Icelandic Sagas and Eddas: Christian Memory of Pagan Practice

By the time the major Icelandic sagas and the Prose Edda were written down, Scandinavia had been Christian for centuries. Boyer insists on this chronological and institutional gap: what modern imagination calls the “pagan North” is accessed mainly through Christian-period texts, produced within a literate, church-shaped culture.¹ Saga authors were commonly clerics, or laymen formed within clerical education; their intellectual world was already structured by Christian historiography, moral theology, and Latin book culture.¹ The result is not that sagas are useless for earlier religion, but that their evidentiary category must be stated accurately: they are Christian-era representations of remembered paganism, not pagan documentation speaking in its own voice.¹

Hagiography, providential historiography, and saga narrative forms

Formally, kings’ sagas and conversion narratives often operate with Christian narrative habits: they moralise history, organise episodes around providential turning points, and present exemplary figures whose lives display conversion, judgement, and divine sanction.¹ This matters for midwinter material. When a saga depicts a ruler struggling to reshape jól practice, or stages confrontations between mission and local cult, the narrative grammar is rarely neutral description; it is didactic historiography in which “heathen” practice is rhetorically positioned as contrast or foil.² Reading such scenes as direct field reports of Viking-age ritual mistakes genre for ethnography.

Oral tradition, reliability, and the limits of reconstruction

A common defence of “pagan Yule” reconstructions appeals to oral tradition: even if the written texts are late, they are said to preserve old lore intact. The safer methodological posture is more restrained. Oral transmission can preserve motifs and narrative structures, but it is also capable of compression, elaboration, and reinterpretation—especially across the upheaval of conversion and the long interval between event and redaction.¹ In Iceland, pre-Christian stories survived precisely because they were retold in Christian households and recorded by Christian writers for Christian audiences; that process makes some degree of reframing likely.¹ The sagas are therefore best treated as witnesses to mediated memory, not as secure blueprints of ninth-century ritual.

Hvítakristr, Baldr, and the temptation of over-syncretism

The epithet Hvítakristr (“White Christ”) is sometimes treated as a syncretic “smoking gun”: Christ, it is claimed, must have been assimilated to Baldr the shining god, so Christian “light” language is simply solar or Baldr cult in new dress. This inference overreaches. “White” in medieval Christian usage is already a dense symbol of purity, baptismal garments, resurrection glory, and sanctity; it does not require a Baldr allusion to be intelligible.¹

More importantly, nothing in the sources compels a direct line of derivation from Baldr to Christ. Similarity at the level of generic “brightness” symbolism may indicate shared human metaphors or broad mythic patterns; it does not, by itself, establish the historical claim that “Christ is just Baldr renamed”. Boyer’s caution is decisive here: parallels are cheap, derivations are hard, and in a Christian textual environment, Hvítakristr can be explained adequately within Christian semantics alone.¹

Case-study protocol: how this article will treat “syncretic-looking” motifs

Given these constraints, any motif that appears syncretic—a “Yule” moved to 25 December, a “White Christ,” a midwinter boar feast, solar metaphors in Christian preaching—will be handled according to a consistent protocol in this article.

First, dating and context: when was the source written, by whom, and for which audience? Texts composed in a Christian milieu will be treated as Christian discourse about earlier practice unless proven otherwise.

Secondly, genre and function: we read each passage as saga, law, homily, computus, or liturgical text, and ask what rhetorical work the motif is doing in that genre.

Thirdly, comparative control: we compare “pagan-looking” elements with securely dated Christian usages elsewhere (for example, Anglo-Saxon geola language integrated into Christian martyrological writing) and, where possible, with non-textual evidence.

Fourthly, direction of borrowing: where similarity exists, borrowing from Christianity into popular practice will be treated as at least as plausible as the reverse, since Christian calendars and feasts are demonstrably older than our earliest named attestations of “Yule” in northern Christian texts.

Finally, level of claim: we distinguish between (a) shared symbolism, (b) local Christian adaptation of seasonal custom, and (c) robust claims of cultic continuity. Only (a) and cautiously (b) will be admitted without first-tier evidence; (c) will be treated as unproven unless supported by contemporaneous sources.

Applied to Icelandic and Anglo-Saxon material, this protocol allows us to acknowledge overlap and complexity without collapsing Christmas into a “solar cult” or turning jól into a monolithic pre-Christian festival out of which Christian Christmas supposedly evolved.³

- Régis Boyer, Le Christ des barbares. Le monde nordique (IXe–XIIIe siècle) (Paris: Cerf, 1995), on the Christian context of saga production, clerical formation, and the shaping of pre-Christian memory.

- Alison Finlay and Anthony Faulkes, trans., Heimskringla, vol. 1: The Beginnings to Óláfr Tryggvason (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London, 2011), Hákonar saga góða (for an example of “conversion-story” framing around jól and Christian alignment).

- Régis Boyer, Le Christ des barbares (as in n. 1), methodological cautions on using saga material to reconstruct pre-Christian rites and the tendency of later texts to reframe earlier practice.

Folk Christianity, “Celtic Survivals” and the Mirage of Pure Pagan Continuity

Holy wells and “Celtic” fountains: Roman water cults and Christian re-use

Sacred springs are a classic field in which “Celtic survivals” are asserted with confidence, and where the evidence typically proves more stratified. Across Gaul and Britain, many venerated wells and springs show multi-period use: a site may carry pre-Roman importance, receive Roman-era monumentalisation or dedicatory practice, and later be Christianised through chapels, crosses, saints’ legends, and parish ritual. In such cases, the continuity is often topographical rather than doctrinal: the place remains compelling, but its interpretive frame changes.

This layered pattern matters for method. When later observers label a site “Celtic”, they often compress centuries of re-coding into a single “pagan origin”, mistaking the persistence of a location (water, healing, boundary space) for the persistence of a cult. The older the place, the more tempting the story of unbroken survival—and the more likely that what survives is an inhabited landscape with successive interpretations rather than a single rite conserved intact.

French rural “sorcery” and the invention of a Celticised past

French rural Catholicism offers a useful analogue to the northern evidence. Well into the modern period, clergy and observers report practices that sit awkwardly beside official liturgy: healing rites at springs, protective charms, seasonal processions, and semi-clandestine uses of prayers and sacred names. Nineteenth-century romantic antiquarianism frequently interpreted such practices as residues of a druidic substratum—“half-baptised” survivals of an older Celtic religion. For more on “The Druids”, their origins and demise, read our dedicated Templarkey Druid Special Edition magazine issue 2 (January 2002). There is also an article on “The Culdees” in issue 3 (April 2022) that continues from “The Druids.”

Yet the internal texture of much rural “sorcery” is often thoroughly Christian: crosses, psalms, saints’ names, exorcistic formulas, and Marian invocations, refracted through popular understandings rather than preserved as an intact pre-Christian priestly system. The more plausible model is not “pure pagan continuity”, but folk Christianity operating on old sites and old seasonal rhythms, continually adapting, forgetting, and reinventing. Templarkey has a Witchcraft Special Edition magazine, Issue 8 (July 2023), for Pagan Temples & Christian Witches, as well as Popular Christianity, which predates Wicca by centuries.

This is structurally analogous to the caution Boyer urges for the Nordic world: Christian cultures remember, narrate, and sometimes domesticate a pre-Christian past through Christian genres and sensibilities.¹

What such cases teach us about reading Yule and midwinter customs

Holy wells and “Celtic survivals” illustrate three recurrent distortions that also shape popular writing on Yule: (i) treating any old rural practice as pre-Christian, (ii) conflating continuity of place with continuity of cult, and (iii) projecting modern identity-concerns back into the early Middle Ages.

Once those distortions are resisted, the Yule dossier looks less like a stolen feast and more like a sequence of mediations. Our earliest hard data for Giuli/Geola and fruma jiuleis occur in Christian contexts: Bede explains a winter season whose key hinge has been aligned with 25 December “when we celebrate the Nativity of the Lord”,² and the Gothic calendar term is embedded in a Christian computistical framework.³ The Old English Martyrology likewise integrates “Yule” language into a Christian martyrological structure anchored on 25 December.⁴ Later saga material, composed centuries after conversion, belongs to Christian memory-work rather than contemporaneous pagan documentation.¹

The archaeological record can corroborate the obvious: midwinter feasting and winter sacrifice were real in northern Europe. But it does not, by itself, yield a neat, uniform, solstice centred “Yule festival” that can simply be set against a separate, likewise neatly defined, Christian Christmas. The more responsible historical question is therefore not “Which side stole which feast?”, but how late antique and medieval Christians inscribed a theology of Incarnation, light, and time onto calendars and customs that were already complex. In contrast, later centuries (especially modern ones) retrofitted those complexities into the myth of a pure pagan continuity.

- Régis Boyer, Le Christ des barbares. Le monde nordique (IXe–XIIIe siècle) (Paris: Cerf, 1995).

- Bede, De temporum ratione 15 (year-beginning at VIII Kal. Ian.; “when we celebrate the Nativity of the Lord”; Giuli as winter-month vocabulary).

- David Landau, “The Source of the Gothic Month Name jiuleis and its Cognates,” Namenkundliche Informationen 95–96 (2009): 239–248.

- Christine Rauer (ed. and trans.), The Old English Martyrology: Edition, Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), entry for 25 December.

The Birth of the “Solar Christ” in Early Modern and Modern Thought

Charles-François Dupuis and L’Origine de tous les cultes

The systematic “solar” reading of Christianity in the modern period crystallises with Charles-François Dupuis (1742–1809). In L’Origine de tous les cultes, ou Religion universelle (1794–1795), Dupuis argues that religions are, at bottom, misunderstood allegories of the sun’s annual course through the zodiac. Christianity is therefore treated not as the proclamation of a contingent incarnation within Second-Temple Judaism, but as an astral myth assembled from seasonal symbols, celestial mechanics, and comparative parallels.¹

Dupuis’ procedure is not historical in the modern sense. His method is expansive and rhetorically confident, but it typically subordinates chronology, local context, and internal doctrinal logic to a single master-key: the zodiacal schema. Biblical narratives are collapsed into a comparative astral grid in which, for instance, the twelve apostles can be made to mirror the twelve signs. The “Solar Christ” is, in this setting, not the recovery of an ancient tradition but a modern explanatory construction that converts revelation into a universal “religion of nature.”¹

Volney and the Enlightenment astral reading of religion

Dupuis was not alone. Constantin-François de Volney (1757–1820), in Les Ruines, ou Méditations sur les révolutions des empires (1791), develops a parallel astral hermeneutic: the gods of antiquity become poetic names for celestial bodies, and Christianity is presented as another iteration of a cosmic allegory misread as supernatural revelation.²

Where Dupuis works by compilation and comparative apparatus, Volney packages the thesis in a literary-prophetic register. The point is not principally philological; it is polemical and political, designed to relativise confessional claims by dissolving them into the “law of nature” discerned by reason alone.²

Later popular mythicist writers frequently reproduce this Enlightenment move (sometimes knowingly, often second-hand): solar births, zodiacal disciples, “dying-and-rising” templates, and solstice/equinox schematisation recur, typically with declining attention to the constraints of calendars, liturgy, or primary texts (Graves; Murdock/Acharya S; Doherty; Drews).³

The German Religionsgeschichtliche Schule and Sol Invictus

In the later nineteenth century, comparative scholarship associated with the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule gave astral and syncretistic readings a more technical idiom. One influential line of argument proposed that the Christian Nativity on 25 December arose as a substitution for, or “Christianisation” of, a solar feast—often framed via the Chronograph of 354 and its Natalis Invicti entry.⁴ This model remains culturally dominant: Christmas is said to be a rebadged Sol Invictus festival, with Christ simply replacing Sol as “true sun”.

The difficulty is evidential proportion. Specialists have increasingly stressed that the Chronograph is a fourth-century attestation and is weak evidence for origin or causation; and that Christian explanations grounded in computus and integral time (conception/Passion alignment and the nine-month logic) are early, internally coherent, and attested within Christian chronological speculation before the Chronograph can be made to do explanatory work.⁵ On this reading, the “Solar Christ” model is better understood as a reception-historical construction—an interpretive habit with Enlightenment antecedents—than as a conclusion compelled by the ancient evidence.⁵

Masonic historiography: Lenoir, Bègue-Clavel and the Hiram–mystery continuum

Nineteenth-century Masonic historiography provided another channel by which astral and mystery-cult readings of Christianity entered wider culture. In this literature, biblical figures, pagan deities, and lodge ritual are frequently treated as variations of a single perennial tradition, with solar and zodiacal motifs functioning as a universal symbolic grammar. François Bègue-Clavel’s Histoire pittoresque de la franc-maçonnerie et des sociétés secrètes anciennes et modernes (1843) is an explicit example: it threads together Egyptian, classical, and biblical materials, and reads the lodge’s symbolic universe through a comparative “mystery continuum” in which cosmology absorbs theology.⁶

From the standpoint of Christian dogma, the result is a naturalisation of revelation: grace is translated into nature, and the historical specificity of Christ (incarnate, crucified “under Pontius Pilate”) is dissolved into cyclical solar patterns. Modern “pagan origins of Christianity” discourse and much internet mythography about Christmas often inherit this double legacy—Enlightenment astral myth (Dupuis, Volney) and nineteenth-century mythographic synthesis—while ignoring the Creator–creature distinction and the stubborn particularity of calendars, liturgy, and patristic polemic. The irony is that, in claiming to unmask Christianity as solar religion, these authors frequently manufacture a modern solar Christianity that the ancient sources do not require.

- Charles-François Dupuis, L’Origine de tous les cultes, ou Religion universelle, 3 vols. (Paris, 1794–1795).

- Constantin-François Volney, Les Ruines, ou Méditations sur les révolutions des empires (Paris: Levrault, 1791).

- Kersey Graves, The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors: Christianity Before Christ (Boston: Colby & Rich, 1875); D. M. Murdock (Acharya S), The Christ Conspiracy: The Greatest Story Ever Sold (Kempton, IL: Adventures Unlimited Press, 1999); Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle (Ottawa: Canadian Humanist Publications, 1999); Arthur Drews, Die Christusmythe (Jena: Diederichs, 1909).

- Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), with the Chronograph of 354 dossier and the Natalis Invicti entry.

- Steven Hijmans, “Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas,” Mouseion 3 (Series III, 2003): 377–398; Thomas J. Talley, The Origins of the Liturgical Year (New York: Pueblo Publishing, 1986); C. P. E. Nothaft, “The Origins of the Christmas Date: Some Recent Trends in Historical Research,” Church History 81, no. 4 (2012): 903–911; C. P. E. Nothaft, “Early Christian Chronology and the Origins of the Christmas Date: In Defense of the ‘Calculation Theory’,” Questions Liturgiques 94 (2013): 247–265.

- François Bègue dit Timoléon Clavel, Histoire pittoresque de la franc-maçonnerie et des sociétés secrètes anciennes et modernes (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1843).

From Astral Mythography to Internet Myth: Modern Solar Theories of Jesus

Frazer, Cumont, Drews, and the “dying and rising god” template

The modern solar-myth reading of Christianity does not begin with internet culture; it develops out of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century comparative mythography that sought a single explanatory pattern behind diverse religions. James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough popularised an influential template of the “dying and rising god” into which he gathered a heterogeneous set of figures—Osiris, Tammuz, Attis, Adonis, Dionysus—and, by extension, offered a way of reading the Christian Passion and Easter within an agrarian-cosmic cycle.¹

Frazer’s method was explicitly synthetic and often conjectural: disparate, chronologically scattered, and textually uneven data are treated as expressions of one archetype. Later criticism has shown that this “type” is unstable: many of Frazer’s examples either die without returning, or return without a clear death, and the category itself becomes a product of the scholar’s grid rather than an emic description of any single cult.²

Franz Cumont’s work supplied a parallel “cosmic” framework for late antique religion, foregrounding astral symbolism and encouraging models in which mysteries and astrology provide a ready-made matrix into which Christianity supposedly fits.³ Cumont’s influence is undeniable, but many of his strongest lines of dependence (especially neat genealogies from “Oriental” mysteries to Christian forms) have been substantially revised by later historians of Roman religion.³

Arthur Drews’s Die Christusmythe (1909) then weaponised the comparative habit into an overt mythicist thesis: “Jesus Christ” becomes a mythic or astral saviour constructed from Near Eastern and Hellenistic motifs, rather than a historical figure embedded in Jewish history.⁴ Even where Drews’ conclusions were rejected, the underlying habit—motif-matching across cultures without sufficient control for chronology, genre, and local meaning proved durable and migratory.

Acharya S, Freke & Gandy, Doherty, and contemporary mythicists

Much contemporary “solar Christ” discourse is effectively a repackaging of Frazer and Drew’s work for late-twentieth- and early-twenty-first-century audiences. Authors such as D. M. Murdock (“Acharya S”), Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, and Earl Doherty recycle older comparative claims—often via secondary compilations—while presenting them as decisive historical explanations.

Lists of alleged parallels (solar births at the winter solstice, twelve disciples as zodiac, virgin-birth as astral allegory, three-day death/return templates) tend to proceed by accumulation rather than by demonstration: parallels are asserted without sustained engagement with primary texts, with the chronological distribution of evidence, or with the internal logic of the traditions compared.⁵

For the specific Christmas question, the recurring weakness is the same: late, thin, or ambiguous evidence for a “Sol Invictus Christmas” is treated as determinative, while the better-attested Christian chronographic logic (integral time, Passion/conception alignment, and the nine-month schema) is ignored or dismissed without examination.⁶

Atheist popularisers, memes, and the erasure of patristic and liturgical evidence

From mythicist and comparative-religion subcultures, a simplified storyline has migrated into atheist popular media and internet meme culture: “Jesus is just another dying-and-rising sun-god”; “Christmas was stolen wholesale from Sol Invictus / Mithras / Yule”; “the Church concealed pagan origins.” The rhetorical strength of the package lies in its simplicity; its historical weakness lies in what it leaves out.

Two losses are especially relevant here:

First, patristic evidence and liturgical practice are commonly erased: late antique debates about dates, the logic of computus, and explicit pastoral polemic against solar confusion (for example, Leo’s warnings in Rome) disappear, replaced by a single story of clerical “rebranding”.⁶

Secondly, chronology collapses: fourth-century Roman calendar notes, early medieval vernacular season-terms, and very late saga memory are blended into an undifferentiated “ancient paganism” even though the sources are separated by centuries and belong to different genres, languages, and religious contexts.⁶

Similarity is cheap: motif-hunting, base rates, and the fallacy of provenance

Most solar-myth arguments rely on a simple inference pattern: identify a motif (divine birth, light at midwinter, twelve associates, death-and-return), find a resemblance elsewhere, and assert genealogical dependence (“therefore Christianity copied”). This is methodologically fragile.

First, many motifs are anthropologically common: humans everywhere notice winter darkness and returning light; societies widely sacralise birth, kingship, and seasonal rhythms. Similarity alone, therefore, has a low evidential value.

Secondly, base rates matter: in a world with thousands of myths and feasts, some resemblances will occur by chance or by convergent symbolism, and those resemblances prove nothing unless a concrete historical mechanism of transmission is shown.²

Finally, provenance is frequently inferred in the direction of convenience: dependence is assumed to run from “pagan prototype” to “Christian derivative” even when Christian evidence is earlier, more coherent, or better attested—as in the tendency to treat the Chronograph of 354 as an origin-explanation, rather than what it securely is: a mid-fourth-century attestation requiring further argument to establish priority and causation.⁶

Once one insists on strict control of dates, genres, and what ancient actors themselves say they are doing, the “solar Christ” looks less like a lost ancient secret and more like a modern construction: first systematised in Enlightenment and comparative paradigms, then repackaged for contemporary polemics and the attention economy.

- James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, esp. 3rd ed. (1911–1915).

- Jonathan Z. Smith, “Dying and Rising Gods,” in The Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. Mircea Eliade (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 4:521–527.