Unveiling the Hermetic Mysteries: Église Saint-Saturnin de Palairac / Saint Saturnin Church in the village of Palairac, France

Nestled in the picturesque commune of Palairac, Aude, France, the Saint-Saturnin (or Sernin) Church is a testament to centuries of spiritual and philosophical inquiry. While its origins trace back to the medieval era, this modest yet captivating church has become the subject of intrigue, particularly concerning its alleged connections to Hermetic Philosophy, Alchemy, Rennes-le-Château, and local Freemasonry during the 18th century. Scholars and enthusiasts alike have pondered whether the Saint-Saturnin Church delivers a hermetic message encoded within its architecture and symbolism, shedding light on the mystical traditions of the past.

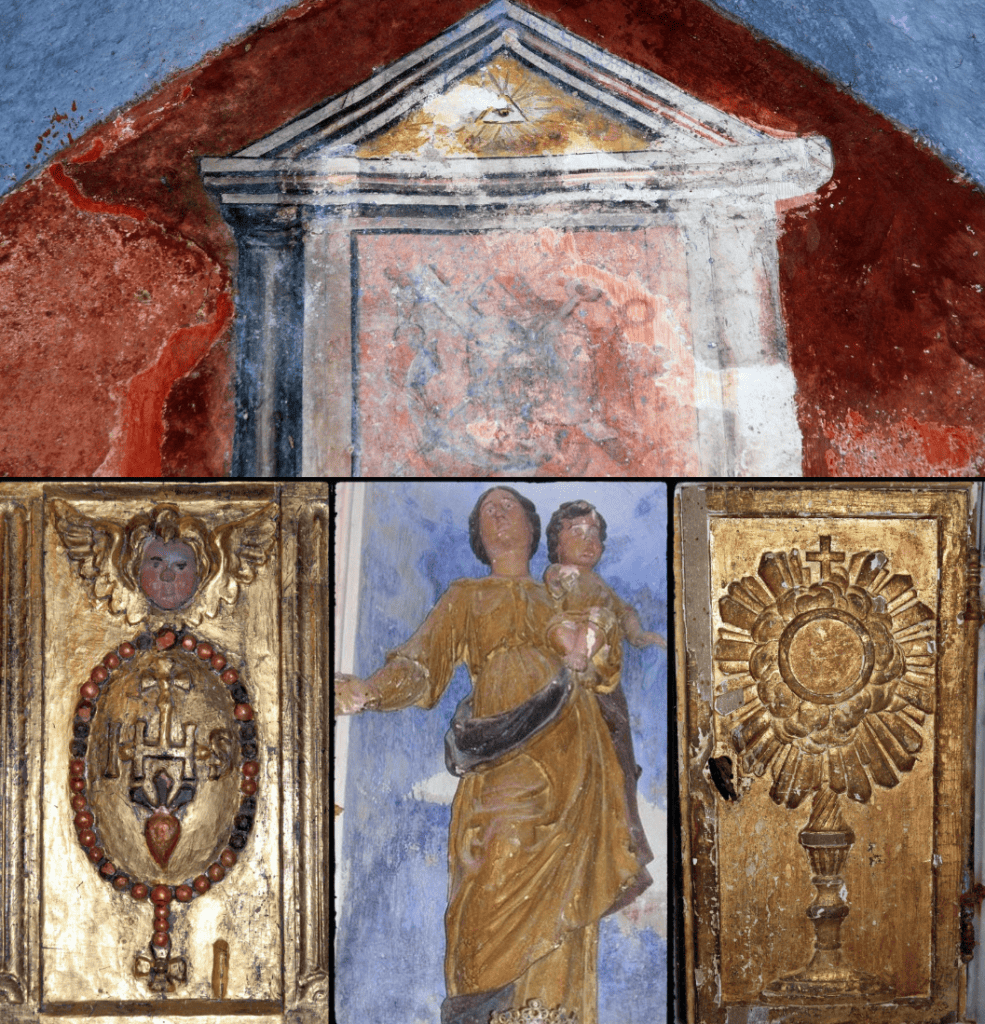

The Saint-Saturnin Church’s association with Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy stems from the intricate symbolism and esoteric motifs adorning its façade and interior. The church’s architectural features, including its portals, stained glass windows, and decorative elements, are believed to contain hidden allegorical references to Hermetic principles such as the unity of opposites, the transmutation of matter, and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. These motifs serve as visual metaphors, inviting contemplation and reflection on the mysteries of existence and the transformative journey of the soul.

The Saint-Saturnin Church’s association with Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy stems from the intricate symbolism and esoteric motifs adorning its façade and interior. The church’s architectural features, including its portals, stained glass windows, and decorative elements, are believed to contain hidden allegorical references to Hermetic principles such as the unity of opposites, the transmutation of matter, and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. These motifs serve as visual metaphors, inviting contemplation and reflection on the mysteries of existence and the transformative journey of the soul.

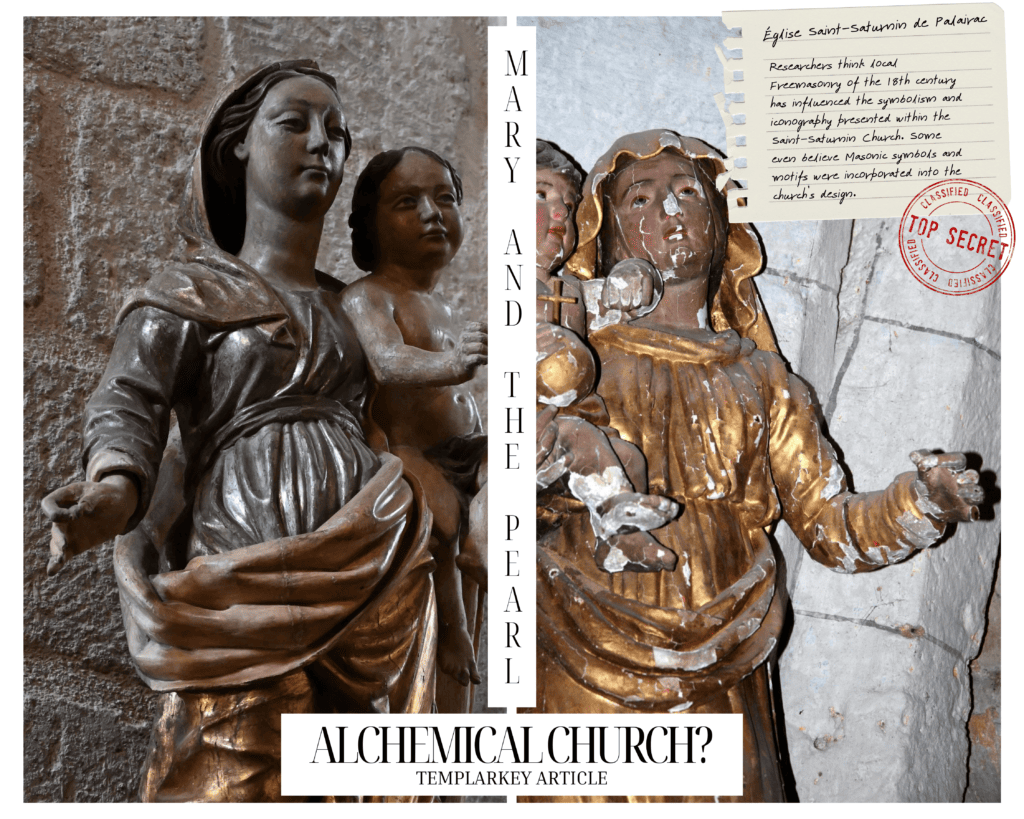

Moreover, certain researchers think local Freemasonry of the 18th century has influenced the symbolism and iconography presented within the Saint-Saturnin Church. Some even believe Masonic symbols and motifs were incorporated into the church’s design. However, seen as Freemasonry evolved via the Craft with its origins within the Roman Catholic Church, these types of churches and their interiors are purely Roman Catholic and not Masonic. A great museum that explains the History of the Crafts, Guilds, and Stonemasons is the Musée du Compagnonnage in Tours, France. Also, the historian of compagnonnage, Jean-Michel Mathonière, has some great articles on his Academia site. Later, Freemasonry, with its emphasis on esoteric knowledge, symbolism, and moral teachings, likely intersected with Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy, forming a tapestry of interconnected spiritual traditions.

Central to the hermetic message purportedly conveyed by the Saint-Saturnin Church is the concept of spiritual alchemy – the inner transformation of the individual to attain spiritual perfection and unity with the divine. Through the metaphorical language of alchemy, this church, like all Roman Catholic churches, communicates the timeless principles of purification, transmutation, and integration, inviting visitors to embark on their alchemical journey of self-discovery and enlightenment.

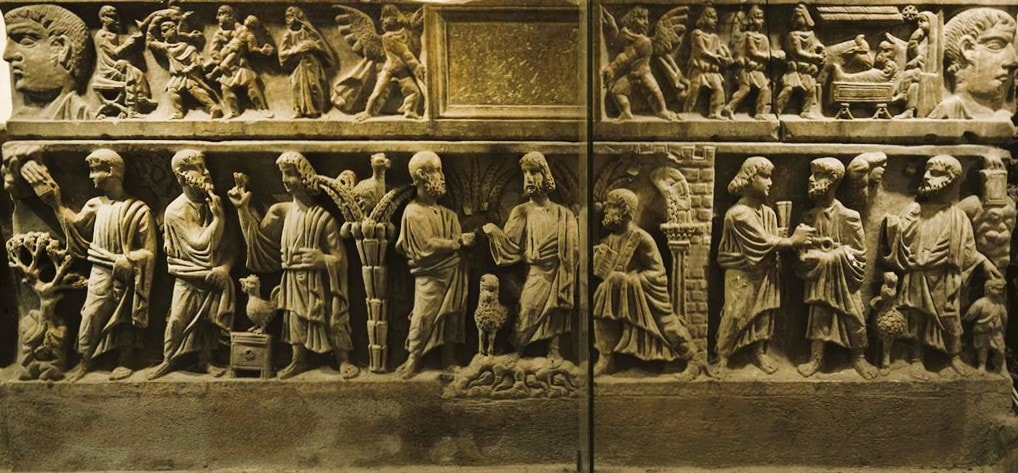

In Alchemy, Christ represents the Philosophical Stone and the Pearl of Wisdom

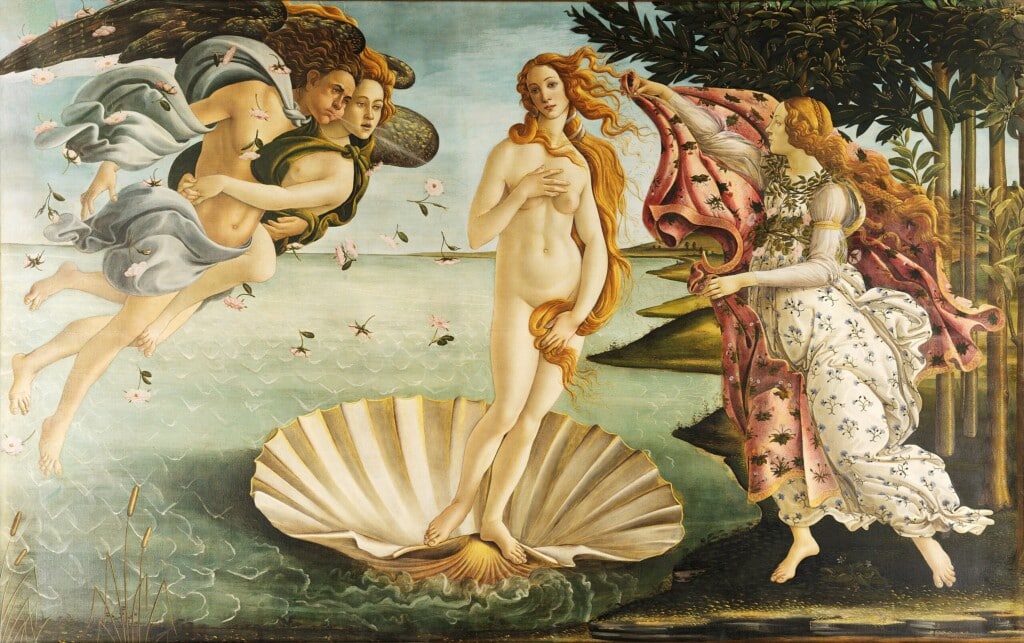

In Christian Alchemy (forerunner to Medeval Alchemy), the Virgin Mary conceived Christ without sex (the Immaculate Conception), and the Pearl was viewed as being created by the shell without sex, by the rays of light from the moon and sun. The Pearl is the symbol of virginity and virtues, referencing both Mary and Christ. Mary is the Concha Mystica (the Mystical shell or the Saint Jacques Scallop) in which the “Verb” and “Light of God” will appear as Christ as a Pearl.

While concrete evidence linking the Saint-Saturnin Church to Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy may be elusive, symbolic motifs and the historical context suggest a deeper layer of meaning embedded within its walls. Whether viewed as a tangible expression of esoteric wisdom or as a product of historical coincidence, the Saint-Saturnin Church continues to intrigue and inspire those who seek to unravel the mysteries of the Hermetic tradition.

The Symbolism Inside the Church: The Virgin Mary and the Pearl in Église Saint-Saturnin de Palairac

Within this church are two statues of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus, with a pearl between her fingers. This imagery of the Virgin Mary holding a pearl between her fingers is a recurring motif in religious art and iconography, sparking curiosity and contemplation among believers and scholars alike. This depiction, steeped in symbolism and spiritual significance, invites exploration into its deeper meanings and theological implications.

One interpretation of the Virgin Mary holding a pearl is rooted in Christian symbolism, where the Pearl represents purity, perfection, and the divine essence. In Christian tradition, pearls are often associated with the Kingdom of Heaven, as referenced in the parable of the Pearl of Great Price in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 13:45-46). The Pearl symbolizes the preciousness of spiritual enlightenment and the soul’s journey towards divine perfection. As the epitome of purity and grace, the Virgin Mary is often depicted as the bearer of this symbol of spiritual purity, embodying the virtues of humility, compassion, and devotion.

One interpretation of the Virgin Mary holding a pearl is rooted in Christian symbolism, where the Pearl represents purity, perfection, and the divine essence. In Christian tradition, pearls are often associated with the Kingdom of Heaven, as referenced in the parable of the Pearl of Great Price in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 13:45-46). The Pearl symbolizes the preciousness of spiritual enlightenment and the soul’s journey towards divine perfection. As the epitome of purity and grace, the Virgin Mary is often depicted as the bearer of this symbol of spiritual purity, embodying the virtues of humility, compassion, and devotion.

Furthermore, the Pearl held by the Virgin Mary may also be interpreted within the context of medieval allegory and mystical symbolism. In medieval Christian mysticism, the Pearl was seen as a symbol of the soul’s journey toward union with God, often depicted in allegorical texts and artworks. As the archetype of divine motherhood and the mediator between humanity and divinity, the Virgin Mary holds the Pearl as a symbol of the soul’s quest for spiritual fulfilment and union with the divine. Moreover, the imagery of the Virgin Mary holding a pearl can be traced back to ancient Eastern traditions, where pearls held significant cultural and religious symbolism. In Eastern cultures, pearls were revered as symbols of purity, wisdom, and spiritual enlightenment, often associated with goddesses and divine feminine figures.

The depiction of the Virgin Mary with a pearl may thus reflect the incorporation of Eastern symbolism into French Christian iconography, highlighting the universal themes of spiritual purity and enlightenment transcending cultural boundaries. In conclusion, the symbolism of the Virgin Mary holding a pearl between her fingers encompasses a rich tapestry of spiritual, theological, and cultural meanings, from representing purity and divine perfection to embodying the soul’s journey toward spiritual enlightenment.

As you have seen with the example of another Virgin Mary and the Pearl from a 10th-century church in France with no link whatsoever with Freemasonry, the symbolism of this theme has no links to the non-Roman Catholic Alchemy of the modern era. The Virgin Mary and the Pearl is Roman Catholic Alchemy; therefore, the symbolism is well-known to those who study theology. Jesus, in his parables, said that the Kingdom of Heaven is like a pearl of great value hidden in a field (within Judaism, Mary (Bet) represents the Kingdom of Heaven). See Matthew 13:44-46. The Pearl is a Christological title and represents the Virgin birth; Christ represents the true Pearl. See John 109.

Other symbols within this church correspond to many different churches, such as the Tables of the Law, the Eye of God (the All-Seeing Eye of the Freemasons), the Holy Sacrament, and the Ark of the Covenant etc. Outside this church is a cemetery with a modern cross of Malta.

Explore this 12th Century Church, its History, and the Liturgical Nicaan Reformation

This church is dedicated to Saint Saturnin; he was the first Christian bishop of Toulouse, better known as Saint Sernin and, in Latin, Saturninus. The legend is that Saint Saturnin lived in the 3rd century and was charged by the Pope to evangelize Gaul, and in Toulouse, he established a small church shortly after his arrival. He had to pass by a pagan temple there, and pagan priests believed that their oracles remained silent due to his frequent presence. The legend continues that the pagan priest seized him and demanded that he sacrifice to their idols; refusing, they tied him to a bull and paraded him around the town. After the rope broke, two devout women gathered his remains and buried them in a deep ditch to prevent the pagans from profaning them.

Why were there kings in the tiny village of Palairac village in the Aude?

This tiny village is on an important border, what is called a March, and in 1283, the King of France, Philip III the Bold, met in Palairac Jacques II, King of Majorca, Count of Roussillon and Cerdagne, and Lord of Montpellier, to discuss the jurisdiction of Montpellier as well as the other castles and villages of the barony. Jacques recognized by an act on August 18, 1283, in Carcassonne the belonging of these places to the kingdom of France. See the General History of Languedoc, sixth volume, page 213.

With its dedication to the legendary Saint Saturninus, this church reminds us of the liturgical conflicts and the importance of the Spanish influence in this region, which was not always French but was part of the March (border) of Spain. The story of the Martyrdom of Saint-Saturnin for Toulouse was the ancient consecration of this city to Christianity. The Spanish March, also known as the Hispanic March, was a military buffer zone established by Charlemagne in 795. Its purpose was to serve as a defensive barrier between the Muslim-ruled Umayyad Caliphate of Al-Andalus (which covered the Iberian Peninsula) and the Frankish Carolingian Empire (encompassing the Duchy of Gascony, the Duchy of Aquitaine, and Septimania). Let’s delve into the origins and development of this intriguing historical region.

Origins:

- The Spanish March resulted from the southward expansion of the Frankish realm from its heartland in Neustria and Austrasia. This expansion began with Charles Martel in 732, following decades of conflict between the Franks and the Umayyads (referred to as the “Saraceni”).

- The Muslim conquest of Spain had reached the Pyrenees. In 719, Umayyad forces surged up the east coast, overwhelming the remaining Visigoth province of Septimania and establishing a fortified base at Narbonne. They secured control by offering generous terms to the local population, intermarriage between ruling families, and treaties.

Conquest and Establishment:

- The Franks gradually extended their influence southward, conquering territories previously part of the Visigothic kingdom of Hispania but were now under Muslim rule.

- The first county to be conquered was Roussillon, along with Vallespir, around 760.

- In 785, the county of Girona, along with Besalú, located south of the Pyrenees, was also taken by Frankish forces.

Geographical Context:

- The Spanish March broadly corresponds to the eastern regions between the Pyrenees and the Ebro rivers.

- The local population of the March was diverse, including Basques, Jews of Occitania, and a large Occitano-Romance-speaking Gallo-Roman population (composed of Occitans and Catalans) governed by the Visigothic Code.

- Over time, these lordships within the March either merged or gained independence from Frankish imperial rule.

Emergence of Autonomous Entities:

- Out of the turmoil of counties in the region, the Principality of Catalonia eventually emerged. It comprised various counties that merged with the County of Barcelona or became vassals.

- Counties that formed part of the March included Ribagorza, Urgell, Cerdanya, Peralada, Empúries, Besalú, Osona, Barcelona, Girona (referred to as the “March of Hispania”), and Conflent, Roussillon, Vallespir, and Fenouillet (referred to as the “March of Gothia”).

The Franks strategically created the Spanish March to safeguard their northern territories and maintain a defensive buffer against the Umayyad Caliphate in Al-Andalus. Over time, this region evolved into a complex network of counties, laying the groundwork for the emergence of Catalonia and other autonomous entities. At the beginning of Christianity, the churches of Gaul sought to base their anteriority on other churches or cities by creating and confirming fictitious and marvellous stories that would become the legends of the saints who brought Christianity to Gaul (legendary stories of the seventy-two disciples). The Provençal legends regarding Mary Magdalene are part of this literature. Every church or cathedral (including Chartres) suddenly discovers various ancient tombs of Gallo-Roman families that are transformed into saints of the church of the Gauls coming from Palestine. The work of the clerics of the Church of the Gauls was then to fix the legends to attract tourism and proclaim its anteriority in other places.

The cult of Saint-Saturnin set the boundaries of the Visigothic Kingdom. Therefore, this is how the definitive version of the “Passion of Saint Saturnin” was written in Prose at the instigation of the Archbishop of Narbonne between 913 and 926. Narbonne is the metropolitan church of Toulouse, which explains the link between this cult of Saint Saturnin and the creation of a Passion that will confirm the antiquity of Christianity in Toulouse. We are in the period when the Carolingian Franks reached Septimania and the March of Spain. A new liturgy was to be imposed throughout the Carolingian Empire. This liturgical reform was inspired by the ancient Hispanic ordines and those of the Roman ordo, coming from the clerics of Narbonne. The bishop of Narbonne took the title of Archbishop in the eighth century, thus showing the importance and extension of the power of his metropolitan church, which he extended to the “Catalan” dioceses of Barcelona, Vic, Girona, and Roda.

A Trinitarian profession of faith is added in the two oldest masses preserved in honour of St. Saturninus, celebrated on November 29 (dies natalis) and November 1 (translatio). Thus, the cult of St. Saturninus by the Passio Narbonnaise (Narbonne Passion) confirms a religious battle begun against Arianism as early as the fifth century. The Abbey of Saint Victor in Marseilles participated in the dissemination of the legends of Saint-Potitus linking to Saint-Saturnin. The ninth century was the time of the difficulties of the March of Spain, still under Visigothic liturgical influence, and bishoprics such as that of Narbonne, where the Roman liturgy was established and confirmed by the creation of the Passio and respect for the doctrine of Nicaea. Saint Saturnin was used to evangelize the north of Spain.

The Basilica of Toulouse and its altar were consecrated to St. Saturninus, with bones of St. Ascicles of Córdoba, also known as St. Cissicles, placed with part of the skull of St. Saturninus. Asciscles is said to have had his tomb desecrated by the Visigothic king Agila. A rural chapel in Palairac was dedicated to this saint to obtain rain after the recitation of hymns, which belong to popular Christianity and Christian magic. Thus, through its dedication, this church makes us enter into the historical links and conflicts between France and Spain, both at the religious and liturgical level, marking this place as belonging to the Nicean Roman Christianity of the Franks.

The Saint-Saturnin de Palairac France church religion was Roman Catholic, and being the only church in Palairac, it served the small village community under the ministry of various priests. This beautiful Romanesque church stands as a monument for the Corbières Minervois tourism industry. Freemasons and Rennes-le-Château researchers visit this church, thinking there are ties and alchemical symbols linking to the mystery of Rennes-le-Château. However, as we have read, the symbology within this and all Roman Catholic churches is straightforward Roman Catholic symbolic imagery and allegory. Read more regarding Palairac on the French website Gazette de Rennes-le-Château, which includes an interview with a past Mayor of Palairac.

References:

Evola, J. (2000). The Hermetic Tradition: Symbols and Teachings of the Royal Art. Inner Traditions.

McLean, A. (2014). The Alchemical Mercurius: Esoteric Symbol of Jung’s Life and Works. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Yates, F. A. (2001). The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. Routledge.

Waite, A. E. (2017). The Secret Doctrine in Israel: A Study of the Zohar and Its Connections. Theophania Publishing.

Gambero, Luigi. Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought. Ignatius Press, 1999.

Otfinoski, Steven. Mary, Mother of God: Her Life in Icons and Scripture. Our Sunday Visitor, 2000.

Schiller, Gertrud. The iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I: Christ’s Incarnation, and Vol. II: The Passion of Christ. A&C Black, 2012.

Woodford, Susan. The Virgin Mary in Late Medieval and Early Modern English Literature and Popular Culture. Cambridge University Press, 2011.