The Ultimate Guide to The Chinon Parchment: Knight Templar Absolution

Introduction to the Chinon Parchment and Knight Templar Absolution

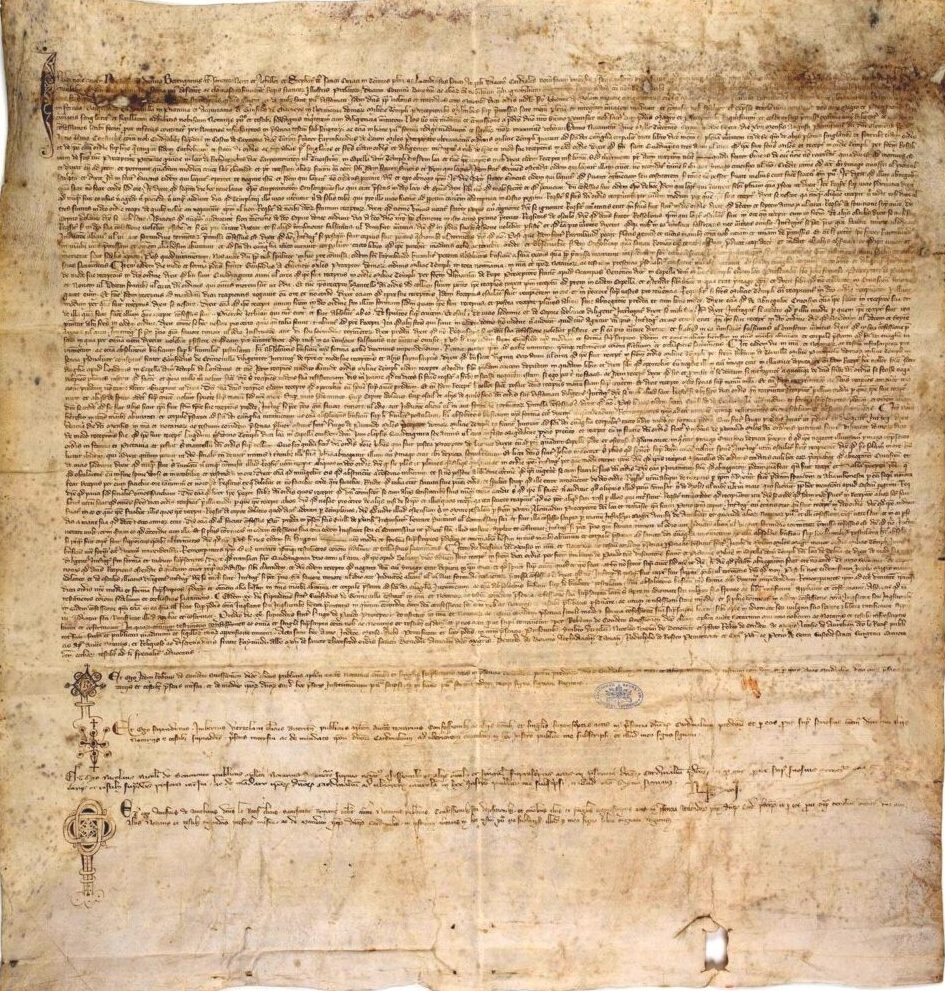

The Chinon Parchment, a document rediscovered in 2001 in the Vatican Secret Archives, plays a pivotal role in understanding the final years of the Knights Templars (Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon). Dating to August 1308, it contains a record of the papal inquiry into the charges brought against the leaders of the Templar Order.

The Chinon Parchment sheds light on Pope Clement V’s absolution of the Templar leaders from charges of heresy—an act that significantly complicates the common narrative of the Templars’ persecution. This article will explore the historical significance of the Chinon Parchment, its content, the context of its creation, and its implications.

Historical Context and History of The Knights Templar

In the early 14th century, the Knights Templar, a powerful military and religious order founded during the Crusades, became the target of King Philip IV of France (Philippe le Bel). Philip, deeply indebted to the Templars, sought to eliminate the order by arresting its leadership in France on October 13, 1307. Accused of heresy, idolatry, and immorality, the Templars were subjected to torture to extract confessions, which led to their condemnation. Therefore, this marked the beginning of a process that would ultimately lead to the dissolution of the order.

The Mass Arrest of the Templars in France (1307)

On the morning of Friday, October 13, 1307—a date that has since gained an almost mythic status as the origin of “Friday the 13th” superstition—King Philip IV of France ordered the simultaneous arrest of all Templars in his kingdom. The coordinated effort implemented by The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon was executed with remarkable efficiency—thanks to secret letters sent to royal officials across France—instructing them to act on the same day. This sudden and comprehensive arrest was planned in utmost secrecy, catching the Templars by surprise. For more on the arrest of the knights Templars on October and Friday the 13th, click here.

The royal agents stormed Templar preceptories, confiscating properties and imprisoning members of the order. In addition to Grand Master Jacques de Molay, many senior Templar leaders were captured in Paris, including the preceptor of Normandy and other high-ranking officials.

- Geoffroi de Gonneville – Preceptor of Aquitaine.

- Hugues de Pairaud – Visitor of France, an important administrative role in the order.

- Geoffroi de Charney – Preceptor of Normandy, one of the highest-ranking Templars after Jacques de Molay.

- Raymbaud de Caron – Commander of the Templar fleet.

- Guillaume de Chambonnet – Preceptor of Poitou and Limousin.

According to historian Malcolm Barber, the order’s central treasury in Paris was seized by King Philip IV’s army during the arrest. However, no contemporary records indicate that any substantial treasure or wealth was found in the Templar preceptories. The swift nature of the arrests in France demonstrates the extent to which King Philip IV sought to suppress the order without warning.

The Question of Templar Treasure

The idea of a hidden Templar treasure has been a popular topic in pseudo-historical accounts, but little evidence supports its existence. Scholars such as Alain Demurger argue that the Templars wealth was not in gold or treasure but in their extensive land holdings, banking assets, and real estate. While the order was undeniably wealthy, their fortune was tied to property and financial services rather than a vast hoard of gold. After the arrests, King Philip IV quickly moved to seize Templar properties—transferring much of their wealth to the French crown and, later, to the Knights Hospitaller.

The Templar Ships at La Rochelle

A key part of the Templar mythos is the fate of the Templar fleet allegedly docked at the port of La Rochelle in western France. Some pseudo-historians claim that the Templars escaped with their treasure aboard ships from La Rochelle, fleeing to destinations such as Scotland or Portugal. However, historical evidence supporting this theory is lacking.

La Rochelle, an important Templar stronghold, was one of the few places in France where the order maintained a fleet. It is true that the Templars used ships to transport supplies and financial assets between their European holdings and the Holy Land during the Crusades. Nevertheless, no credible historical documentation suggests the Templar fleet at La Rochelle played any role in an escape following the arrests of 1307.

Alain Demurger, an expert on Templar history, explains that while the Templars did have ships, there is no evidence to support the notion that they vanished from La Rochelle with treasure. The supposed disappearance of the Templar fleet is more likely a legend than fact, fuelled by later romanticised accounts of the order.

In reality, following the arrests, the French crown quickly took control of all Templar assets, including their ships and ports. It is doubtful that any significant escape of Templars or treasure occurred—given the thoroughness of King Philip IV’s nature regarding the suppression of the Templars. The notion that Templar knights sailed off with any treasure has become part of popular lore, but it lacks substantial historical backing. In reality, virtually everything passed to the Knights Hospitaller (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem), later known as the Knights of Malta, to visit Templar sites at La Rochelle. Click here.

The Role of Pope Clement V and the Roman Catholic Church and Heresy

Pope Clement V, whose papacy was marked by pressure from King Philip IV, was drawn into the Templar controversy. Clement initially attempted to protect the Templars by calling for a formal investigation under the Church’s authority rather than allowing the trials to be entirely under royal control. However, the political and financial power of the French monarchy placed Clement in a difficult position. While the Pope ordered inquiries into the Templars in several European kingdoms—the pressure from Philip led to a complex relationship between the papacy and the monarchy, culminating in the disbandment of the order at the Council of Vienne in 1312.

Trials of the Templars in England

In England, the fate of the Templars followed a slightly different trajectory. After King Philip IV’s actions in France, Edward II of England reluctantly followed suit under pressure from both Philip and Pope Clement V. In January 1308, Edward ordered the arrest of the Templars in England. However, the English trials were notably less brutal than those in France, where torture was heavily used. Instead, the English proceedings, held under the supervision of the Church, were more procedural and less violent.

The trials in England began in London in 1309 and were overseen by a papal commission. Few confessions of heresy were obtained, mainly due to the absence of torture, which was not widely used in England. Many Templars in England defended the order’s practices, and the testimonies they gave were far less incriminating than those extracted under duress in France. Despite this, the Templar properties were confiscated, and their wealth was mainly transferred to the Hospitallers. The Templars themselves were either imprisoned or absorbed into other religious orders, though no large-scale executions took place in England.

Trials of the Templars in Scotland

The situation in Scotland during the early 14th century was complex due to the ongoing Wars of Scottish Independence, led by Robert the Bruce against English forces. At the time of the Templar trials elsewhere in Europe, Scotland was embroiled in conflict and was excommunicated by Pope Clement V because of Robert the Bruce’s defiance of English authority and his role in the murder of John Comyn in 1306. As a result, the influence of both the papacy and the English crown was diminished in Scotland, allowing the Templars there, if any existed, to avoid significant persecution or trials like those in France, England, and other parts of Europe.

Historical Evidence of Templars in Scotland

There is little concrete evidence in historical records to suggest that a significant number of Templars were present in Scotland at the time of the trials. The Knights Templar did have some presence in Scotland, and they owned properties, as they did throughout Europe. One notable example is the preceptory at Balantrodoch (now Temple, Midlothian)—a Templar stronghold until their suppression. However, no historical documents indicate a large-scale arrest or trial of the Templars in Scotland, likely due to the political and military turmoil of the period.

The lack of a formal investigation into the Templars in Scotland may have allowed surviving members of the order to remain in the country. However, historical records of their activities after 1307 are scarce. Any Templars who did survive may have blended into the local population or joined other orders—such as the Hospitallers—to escape persecution.

The Myth of Templars at the Battle of Bannockburn (1314)

A popular legend propagated in later centuries claims that Templar knights fought alongside Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314—where the Scots achieved a decisive victory over the English forces led by Edward II. According to this myth, Templars who had fled persecution in France found refuge in Scotland and played a crucial role in Robert the Bruce’s victory by leading a cavalry charge that broke the English lines.

However, this claim is not supported by contemporary evidence. No medieval chronicles or documents from the time mention the involvement of Templar knights at Bannockburn. Scholars such as Michael Haag and Malcolm Barber—both respected experts on Templar history—have pointed out that the supposed Templar involvement in Bannockburn is a much later invention, likely based on the romanticisation of the order rather than any factual basis. Barber argues that the political and military climate of Scotland during this period would have made the large-scale presence of Templars unlikely, and there is no historical record connecting the Templars to Bannockburn.

A Broader European Perspective

Beyond France, England, and Scotland, the Templar trials unfolded differently across Europe. The trials were far less severe in Spain and Portugal, where the Templars had significant influence. In these regions, many Templar knights were cleared of charges, and the order’s properties were transferred to other military orders, such as the Order of Christ in Portugal, where many former Templars continued to serve. See the Templarkey magazine Issue 6 (January 2023) for the article “What Happened to The Templars & The Portuguese Knights of Christ.” Click here. In Germany, the Templar trials were slow to start and generally lacked the severity of those in France.

The Chinon Parchment must be understood within this broader European context. While it provides a detailed account of the papal inquiry into the Templar leadership in France, it reflects only one part of a complex, continent-wide process of trial, suppression, and dissolution. The relatively lenient treatment of the Templars in England and their near-total escape from prosecution in Scotland highlights the variability in the way different kingdoms handled the papal mandate to investigate the order. These regional differences were driven by local political circumstances and the relationships between secular rulers, the Templars, and the papacy.

Freemasonry and the Creation of the Myth

One of the key points related to the trials of the Templars in Scotland and the myth surrounding their participation at the Battle of Bannockburn involves the later influence of Freemasonry. The modern notion of a historical connection between the Knights Templar and Freemasonry was largely propagated in the 18th century. One of the key figures in this development was Chevalier Andrew Michael Ramsay, whose oration in 1737 tied Freemasonry to the Crusaders and chivalric orders, including the Templars. However, historians have since debunked the idea of a direct link between the medieval Templars and modern Freemasonry.

Ramsay, a Scottish exile involved in the Jacobite Stuart Cause in France, played a critical role in the rise of Templar-related rites within Freemasonry. His oration helped introduce chivalric and Templar degrees into Freemasonry, which were subsequently adopted and proliferated by Masonic groups, particularly in Scotland and France.

The myth of Templar involvement in the Battle of Bannockburn was popularized in the 18th century, largely through the efforts of Freemasonry. Freemasons in Scotland and beyond began to associate themselves with the Knights Templar, claiming a symbolic or even historical continuity between the medieval Templars and the Freemasons. This myth was reinforced by the creation of “Templar degrees” within certain branches of Freemasonry, most notably the Scottish Rite and York Rite.

One of the most significant moments in this myth-making occurred in 1805 when Alexander Deuchar, a Freemason in Edinburgh, established the “Masonic Knights Templar” as part of Scottish Freemasonry. Deuchar and his fellow Freemasons promoted the idea that the Templars had survived their suppression by finding refuge in Scotland, eventually passing on their esoteric knowledge and traditions to the Freemasons. This idea found a receptive audience, particularly as Freemasonry itself drew heavily on mystical and chivalric imagery.

The supposed link between the Templars and Bannockburn became part of this larger narrative. Freemasons portrayed the Templars as noble warriors who had escaped the unjust persecution of the Church and monarchy, living on through secret orders like the Freemasons. In fact, some versions of the legend claimed that Robert the Bruce himself established a secret order of Templars after Bannockburn, though there is no historical basis for this claim.

Historical Critique of the Myth

Modern historians reject the idea of Templar involvement in Bannockburn as a product of later Masonic invention rather than historical fact. While the Templars did have some holdings in Scotland prior to their suppression—their numbers were likely small—there is no contemporary evidence to suggest that they had any military involvement in the Wars of Scottish Independence. Moreover, Robert the Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn is well-documented in medieval chronicles, none of which mention the Templars.

According to academic research, the myth’s popularity stems from a combination of romanticized ideas about chivalry, Freemasonic symbolism, and the enduring allure of the Templar mystique. Scholars like Helen Nicholson have noted that the posthumous reputation of the Templars often takes on a life of its own, shaped more by later cultural and esoteric movements than by the historical realities of the 14th century.

The trials of the Templars in Scotland, or rather the lack thereof, are a testament to the unique political circumstances of the country during the early 14th century. Though captivating, the legend of the Templars fighting at the Battle of Bannockburn has no basis in contemporary historical records. Instead, this myth was later constructed by Freemasons and other groups who sought to draw symbolic connections between themselves and the medieval Templars. The allure of the Templars as hidden survivors of persecution continues to fuel these myths despite the lack of historical evidence supporting such claims.

The Parchment’s Discovery and Content

The Chinon Parchment was discovered by historian Barbara Frale in 2001 among documents in the Vatican Secret Archives. The term “secret” in “Vatican Secret Archives” (Archivum Secretum Vaticanum) does not imply secrecy in the modern sense of the word. Instead, it refers to something private or personal. In this context, the “Secret Archives” are the Pope’s personal, private archives, not something hidden from the world. Written in Latin, the parchment details a private hearing held at the Château de Chinon, where three cardinals—Berenger Fredol, Etienne de Suisy, and Landolfo Brancacci—acting on behalf of Pope Clement V, interrogated the Templar leaders, including Grand Master Jacques de Molay.

The document reveals that during the trial, the Templar leaders admitted to certain charges, such as denying Christ under pressure during their initiation rituals. However, these admissions were later attributed to misunderstandings rather than wilful heresy. Most importantly, the Parchment records that Pope Clement V absolved the Templar leaders of heresy—though he did not exonerate them from other accusations or the administrative shortcomings of the order.

The Debate Over Heresy and the Papacy’s Role

The absolution of the Templar leaders in Chinon contradicts the later public narrative of the Templar Order’s guilt. While the Templars were ultimately disbanded, the Parchment demonstrates that Pope Clement V did not believe the charges of heresy warranted their excommunication. Instead, the dissolution of the order appears to have been a political decision driven mainly by King Philip IV’s demands.

Several academic discussions surround the reasons why Pope Clement V—despite absolving the Templar leaders of heresy—allowed the dissolution of the order. Some historians argue that the Pope was acting under extreme pressure from Philip IV, whose political and military power at the time outweighed the Pope’s influence. Others suggest that Clement sought to preserve the unity of Christendom by avoiding a direct confrontation with the French monarchy, which was a leading power in Europe at the time. Clement’s ambiguous role has been a subject of debate among scholars, including Malcolm Barber and Alain Demurger.

The Council of Vienne (1311–1312) and the Papal Bull

The Council of Vienne opened in October 1311 with representatives from across Christendom. The question of the Templars fate was fiercely debated. Pope Clement V had not been fully convinced of the order’s guilt, and many church officials at the council were hesitant to condemn the Templars without sufficient evidence. However, the enormous political pressure from Philip IV, combined with the confessions extracted during the Templar trials in France, made it difficult for the Church to resist.

In March 1312, after much deliberation, Pope Clement V took the decisive step of disbanding the Knights Templar, not through a formal declaration of heresy, but by means of the papal bull Vox in excelso, issued on March 22, 1312. This bull formally dissolved the Templar Order, stating that the decision was made not as a direct condemnation of the order’s innocence or guilt but to maintain peace within the Church and prevent further scandal. The dissolution was portrayed as an administrative necessity rather than a theological judgment.

Vox in excelso (1312)

The bull Vox in excelso officially disbanded the Knights Templar and transferred their assets to the Knights Hospitaller. It emphasised that the decision was made in the interest of Church unity and to avoid discord within Christendom. The bull stated:

“We declare, with the approval of the sacred council, that the Order of the Knights Templar shall be suppressed and abolished for all time, and their habit and name completely prohibited.”

Importantly, the bull did not explicitly condemn the Templars as heretics. Instead, it stated that their suppression was a prudential measure, taken to safeguard the Church and avoid further scandal. The assets of the Templars were to be transferred to the Knights Hospitaller, though in practice, much of the Templar wealth was absorbed by the French crown.

Aftermath and Significance

While Vox in excelso formally dissolved the Templar Order, the papal bull Ad providam (1312) later confirmed that the bulk of the Templar properties would be transferred to the Knights Hospitaller. However, in regions such as France, King Philip IV retained control over much of the Templar wealth.

The dissolution of the Templars at the Council of Vienne and through Vox in excelso marked the end of one of the most powerful military orders of the Middle Ages. Despite the lack of formal condemnation for heresy, the Templars dissolution was seen by many as politically motivated. The Templars had played a significant role in the Crusades and European politics. Still, their fall was ultimately due to the complex interplay of financial, political, and ecclesiastical forces in early 14th-century Europe.

The decisions made at the Council of Vienne have remained a subject of debate among historians, with many emphasising the role that political pressures—particularly from King Philip IV—played in the downfall of the Templars. The papal bulls associated with the council, especially Vox in excelso, represent the Church’s attempt to navigate these political currents while maintaining its authority.

Primary Sources and Scholarly Interpretations

The Chinon Parchment itself is one of the key primary sources regarding the trials of the Knights Templar. Its importance lies in the fact that it provides an official papal document that absolves the Templars of heresy, contradicting the image of the Templars as heretics perpetuated by Philip IV’s court and the later burning of Grand Master Jacques de Molay in 1314. The Parchment is available in the Vatican Secret Archives and was first transcribed and published by Barbara Frale in her book The Templars: The Secret History Revealed.

Historians like Malcolm Barber and Alain Demurger have analysed the Chinon Parchment in the broader context of Templar history. In his work The Trial of the Templars, Barber argues that the trial was less about genuine concern for heresy and more about Philip IV’s desire to seize Templar wealth. Demurger, in The Last Templar, provides a comprehensive overview of the fall of the Templars and the role of Pope Clement V, suggesting that the Pope’s actions reflected a combination of political expediency and papal weakness.

Broader Implications of the Parchment

The Chinon Parchment has broader implications for our understanding of medieval power dynamics between the Church and the monarchy. It illustrates the precarious position of the papacy in relation to the secular rulers of the time, particularly the French monarchy. While the Church maintained doctrinal authority, the Chinon Parchment shows that it was not immune to the pressures of political and financial influence.

Moreover, the document challenges the common perception of the Templars as heretical and blasphemous. The admissions made by the Templar leaders, while damning in some respects, were mitigated by the Parchment’s clarification that these were misunderstandings rather than genuine heretical beliefs. As such, the Parchment raises questions about the justice of the Templars persecution and whether they were victims of political machinations rather than theological condemnation.

Legacy and Modern Interpretation

The Chinon Parchment has contributed significantly to the rehabilitation of the Templars’ image in modern times. Its rediscovery in 2001 revealed that Pope Clement V had absolved the Templar leaders of heresy, contradicting the popular narrative of the order’s guilt perpetuated by King Philip IV and the brutal trials in France. This document, therefore, served as a critical piece of evidence in reconsidering the fairness of the Templars persecution.

The Vatican’s Modern Reconciliation with the Templars

In the 21st century, the Vatican took a further step in addressing the historical treatment of the Templars. In 2007, as part of the publication of the Chinon Parchment, the Vatican formally recognised that the Templars had been wrongfully accused of heresy. Pope Benedict XVI, who was the reigning pontiff at the time, authorised the release of the document and endorsed a scholarly review of the events leading to the suppression of the Templar Order.

Although Pope Benedict XVI did not issue a formal apology in the way we might expect from modern political or diplomatic gestures, the Vatican’s actions were seen as an important acknowledgement that the trials and dissolution of the Templars had been unjust. By publishing the Chinon Parchment and other related documents, the Church effectively sought to clear the Templars’ name and bring closure to a historical controversy that had persisted for centuries.

The Parchment’s Influence on Historical Narratives

The absolution recorded in the Chinon Parchment, and the Vatican’s modern actions have played a significant role in the Templars rehabilitation in historical and popular imagination. Templar revivalist groups, historians, and authors often cite the Parchment as proof that the Templars were victims of political manoeuvring rather than genuine heretical practices. The document challenges the image of the Templars as heretics and presents them as loyal Christians caught in a power struggle between the papacy and the French crown.

In academic circles, the Chinon Parchment continues to provoke discussions about medieval justice, the relationship between the Church and the state, and the nature of heresy trials. The trials of the Templars are now increasingly viewed through the lens of political intrigue, financial motivation, and the limits of papal power. Scholars such as Malcolm Barber and Alain Demurger emphasise that the dissolution of the Templars was less about theology and more about the political ambitions of King Philip IV.

Popular Culture and Modern Templar Movements

The Chinon Parchment and the Vatican’s acknowledgement of the Templars wrongful persecution have also influenced modern Templar movements and popular culture. Several neo-Templar groups have emerged in recent years, drawing on the Templars legacy of military valour and religious devotion. These groups often claim the mantle of the original Knights Templar, interpreting the Chinon Parchment as vindication of their continued existence.

In popular culture, books, films, and video games often portray the Templars in a heroic light, capitalising on the mystery and romance surrounding the order. The release of the Chinon Parchment has added to the mystique, reinforcing the narrative that the Templars were wrongfully destroyed by a corrupt political system. This narrative shift is evident in works such as The Da Vinci Code and various documentaries that explore the “lost” history of the Templars.

Conclusion

The Chinon Parchment remains a crucial document for understanding the legacy of the Knights Templar. Its rediscovery has changed how historians view the Templars final years and has led to a broader re-evaluation of their role in medieval Christendom. The Vatican’s modern recognition of the Templars innocence, supported by the publication of the Chinon Parchment, has contributed to the order’s rehabilitation and has fuelled a resurgence of interest in their history. Whether viewed through the lens of historical scholarship, modern spirituality, or popular culture, the Templars’ legacy endures, shaped in part by the revelations in this remarkable document.

References

Frale, B. (2004). The Templars: The Secret History Revealed. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Barber, M. (2006). The Trial of the Templars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Demurger, A. (2014). The Last Templar. London: Profile Books.

Vatican Secret Archives, Archivum Secretum Vaticanum, Chinon Parchment (1308), reproduced 2007.