Horse of St Derfel: Holy Stag? Welsh Derfel and King Arthur

Explore the origins of the horse of St Derfel, King Arthur, and his connections to the Welsh Saint Derfel Gadarn, his Holy Stag, and St Derfel’s religious life.

Introduction: The Horse of St Derfel, Llandderfel, and the Lost Welsh Cult

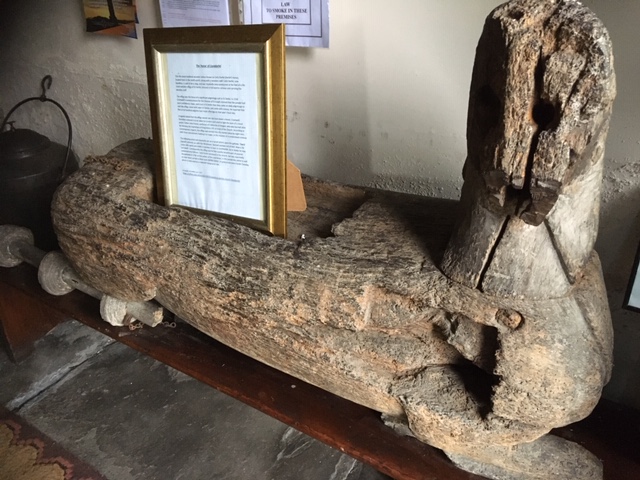

In the quiet village of Llandderfel, Gwynedd, stands one of Britain’s most evocative survivals of late-medieval devotion: the so-called “horse of St Derfel”. Edward Lhuyd’s Parochialia (c.1698) records that a figure of St Derfel Gadarn once dominated the Church, attracting pilgrims who offered money, animals, and prayers for healing and protection (Lhuyd, Parochialia, National Library of Wales MS). This cult was so renowned that it drew the attention of Thomas Cromwell during the reign of Henry VIII, known as the Henrician Reformation. In 1538, Cromwell’s agent Elis Price reported that five or six hundred pilgrims had offered to the image in a single day, some with cattle and horses, so confident were they that St Derfel:

“Had power to fetch him or them that so offer out of hell when they be damned” (D.H. Thomas, A History of the Diocese of St Asaph, 1874).

The parishioners offered £40 to retain the wooden statue of Saint Derfel. However, during the English Reformation, his wooden effigy was famously seized and sent to London to be used as a stake to burn the Jesuit priest John Forest, Franciscan confessor to Catherine of Aragon:

“An act remembered as fulfilling a local prophecy that Derfel would one day set a forest alight” (Thomas, 1874).

St Derfel’s Church is dedicated to Derfel Gadarn—“Derfel the Mighty”—a warrior-saint celebrated in medieval Welsh poetry who, according to tradition, fought at Camlann alongside King Arthur before laying down his arms to embrace the monastic life—he is credited with founding a religious community at Llandderfel and:

“Is said to have ended his days on Bardsey Island” (S. Baring-Gould & J. Fisher, Lives of the British Saints, 1908).

The present building dates from the early Tudor period, and its sheep-grazed churchyard still evokes its former pilgrimage setting. Before the Reformation, St Derfel’s wake day on 5 April featured elaborate festivities built around two massive wooden images—one of a mounted knight and the other a stag—carried out to Bryn Derfel:

“To enact ritualised hunting scenes that dramatised Derfel’s power and Christ’s triumph over evil” (Kathryn Hurlock, Medieval Welsh Pilgrimage, 2018).

Morgan Herbert’s will of 1526 lists Llandderfel among five pilgrimage sites for which he left offerings, confirming its regional significance. These traditions reflect not only Derfel’s local sanctity but also his place in a much wider cultural memory. Medieval Welsh genealogies root Derfel in the heroic past. The Bonedd y Saint lists him as the son of Hoel ap Emyr Llydaw (also known as King Hoel, Sir Howel, Saint Hywel and Hywel the Great), the semi-legendary ruler of Brittany, said to have been exiled in Dyfed before reclaiming his throne.

This lineage made Derfel both of royal blood and kin to the Arthurian circle: Geoffrey of Monmouth names Hoel as Arthur’s ally and kinsman. According to tradition, Derfel himself fought at Camlann, the final battle of Arthur, before renouncing the sword and embracing the religious life.

This Arthurian pedigree enhanced the prestige of his cult, linking Llandderfel not only to the monastic sanctity of Bardsey Island but also to the legendary chivalric world of Britain’s golden age.

Remarkably, a fragment of the animal figure known as the Horse of St Derfel—traditionally identified as a horse—survived Cromwell’s confiscations, remains in the church porch today, semi-headless and partially legless but monumental. Its seated posture with folded legs, hollow body, and Eastertide use suggest that it may represent not a mere mount but a theological image: a White Stag of Easter uniting Arthurian legend and Catholic Christology in a single proclamation.

Saint Derfel, Saint Edern, and the Stag: Christian Iconography and the Path of Sanctity

In the parish church of Llandderfel in Merionethshire stands one of the rarest survivals of medieval devotion: a great wooden animal, its head long ago hacked away, its legs folded beneath its body. Known locally as Cefyl Derfel (“Derfel’s horse”), this battered figure was once part of the life-sized cult statue of St Derfel Gadarn—“Derfel the Mighty,” the Arthurian warrior turned hermit and abbot.

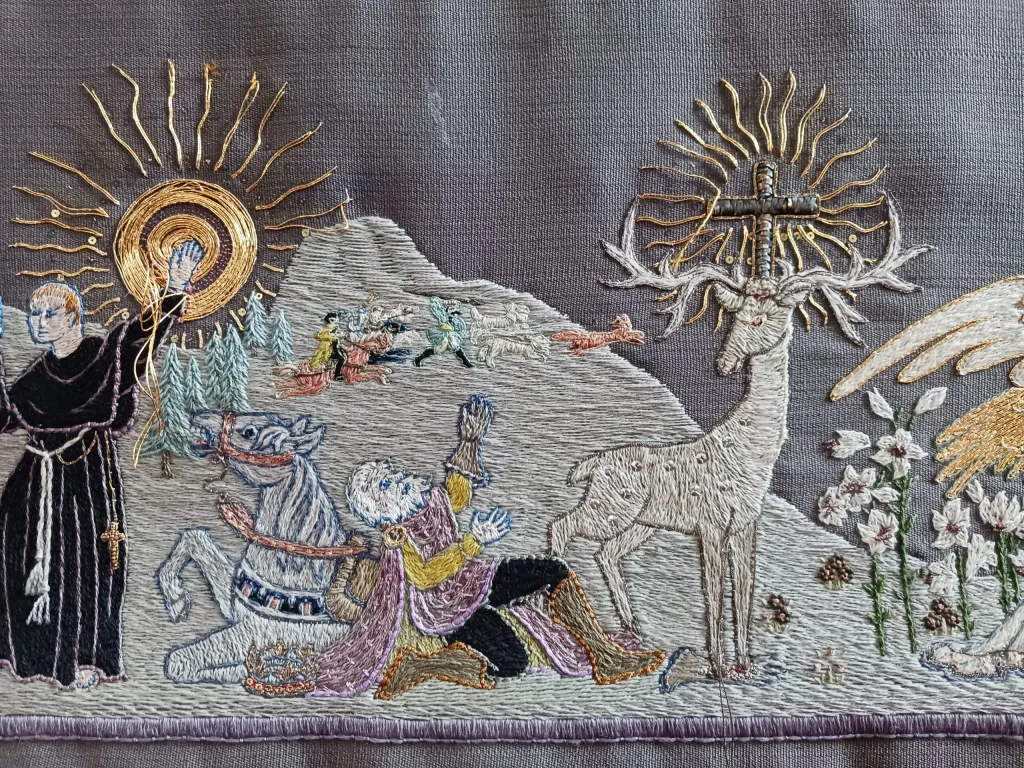

Recent research by Dr Madeleine Gray confirms that this “horse” was in fact a stag, vividly painted, partly articulated, and used in the parish procession on Easter Tuesday. Children were seated upon it as part of a tactile rite of blessing. This discovery places Derfel alongside St Edern, whose Breton legend famously tells of a hunted deer that sought sanctuary under his robe, became tame, and became his mount. Together, these two saints belong to a Welsh-Breton tradition in which the Stag serves as a sign of conversion, divine mission, and sanctified power.

Christianity in Wales: Historical Backdrop (400–1500)

Roman Roots (before 400–c.450). By AD 314, Britain had bishops at the Council of Arles, proving the existence of an organised episcopate. Christianity survived the Roman withdrawal (c.410) and remained strong in south Wales.

Migration and Monasticism (450–600). The collapse of Roman order brought migrations of Irish and Romano-British Christians westward. Saints such as Dyfrig, Illtud, Cadoc, Teilo, and David established clasau (monastic centres) which became bases for mission, education, and manuscript production. Warrior-saints like Derfel and Edern belong to this generation: men who fought, then converted, and evangelised the countryside.

Distinctive Welsh Church (600–800). The Welsh Church was organised around monasteries and abbots rather than diocesan bishops, but remained doctrinally Catholic. Local saint cults multiplied, with relics, holy wells, and crosses forming a Christian landscape. This is the matrix in which the stag motif entered the iconography of saints.

Viking Raids and Norman Reform (800–1200). Monastic sites were attacked but rebuilt. After the Norman conquest, diocesan structures were strengthened, pilgrimage promoted, and churches rebuilt in stone. Norman reform did not erase local devotions but layered new liturgical forms on them, allowing cults like Derfel’s to flourish.

Late Medieval Devotion (1200–1500). By the later Middle Ages, pilgrimage was at its peak. Llandderfel drew hundreds on Derfel’s feast day, with offerings of cattle and horses. His statue, with its companion stag, became a focus of regional identity and devotion.

Derfel Gadarn: Warrior-Saint and His Stag

Derfel’s effigy portrayed him as an armed warrior rather than a monk. Beside him stood the painted, jointed Stag with eyes that could blink—a dramatic focus for pilgrims. Its annual procession on Easter Tuesday blessed the whole parish. The tactile practice of seating children on its back shows how it was a catechetical object, not a mere decoration: it allowed the faithful to participate physically in the saint’s power and intercession.

Saint Edern and the Breton Tradition

Edern’s legend is equally striking. A stag pursued by hunters took refuge under his robe, was spared, and followed him thereafter. In another version, Edern rode the Stag through the night, marking the boundaries of the land he was to Christianise. In Brittany, Edern’s iconography is dual: at Plouedern, Edern holds a book with a crouching stag at his side, emblem of nature subdued and reconciled—at Lannédern, he is mounted on a stag, tracing the territorial limits of his mission. This dual image shows that the Stag could be either companion or mount—both forms expressing the saint’s dominion over creation and his role as missionary.

Biblical and Patristic Foundations of the Stag Symbol

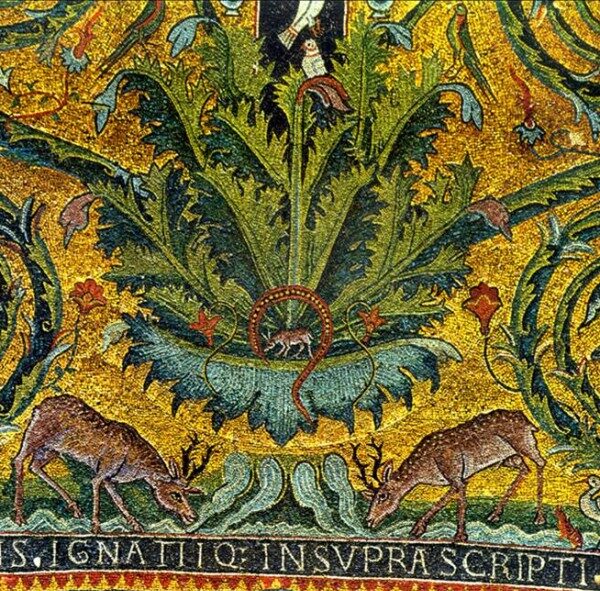

Psalm 42 and the Catechumen. “As the deer longs for streams of water, so my soul longs for you, O God.” Patristic authors such as Augustine and Jerome saw the Stag as the catechumen thirsting for baptism, who first kills the serpent (vice, the devil) and then runs to the font to purge the poison. Medieval theology mapped a progression: penitence (devour the serpent), baptism (drink), growth in virtue (shed antlers of pride), contemplation (ascend the mountains), and death in Christ (funerary Psalm).

Song of Songs 2:8–9. Origen interprets the leaping Stag as Christ Himself, springing from prophet to apostle to saint: “He made like unto a roe… because its sight is keener than that of any other animal, and… a hart, because He comes to destroy the serpent.” The Christian who becomes a “mountain” allows Christ to leap upon him—to make him a bearer of grace for others.

Hildegard of Bingen. Hildegard sees the Stag’s renewed antlers as a sign of spiritual rebirth and its thirst as the soul’s longing for God. Thus, the Stag becomes a figure of resurrection and persevering desire.

The Stag as a Map of the Christian Journey

Art and liturgy made the Stag a catechetical map. Conversion was figured as the devouring of the serpent—renunciation of sin. Baptismal grace was rendered as the sprint to the waters—new life. Virtue and growth appeared in the yearly shedding of antlers—purification from pride. Contemplation was evoked by the leaping to mountain pastures—union with God. Death and fulfilment followed in Psalm 42 at funerals—the final satisfaction of desire in God. Derfel’s Stag, crouching yet processional, and Edern’s Stag, crouching or mounted, visually enact this path: they are sermons in wood, drawing pilgrims from hearing to seeing, from seeing to touching, from touching to imitating the saint’s own journey.

Material Analysis: Oak, Craftsmanship

The surviving wooden figure is carved from a single block of oak, darkened by centuries of handling. Its robust massing, elongated head, deep drilled sockets, and stylised incisions indicate purposeful, processional-grade craftsmanship intended to be seen from a distance and physically engaged with—carried, touched, even kissed by pilgrims. It was almost certainly polychromed. Conservation work by the National Museum of Wales noted tool marks and pigment traces comparable to other Romanesque Welsh wooden figures.

“Medieval sculptures were commonly prepared with a gesso ground and painted in vivid mineral colours, sometimes gilded, to heighten liturgical impact” (National Museum of Wales, Conservation Notes; cf. Romanesque polychromies at Llanbadarn Fawr and Capel-y-ffin).

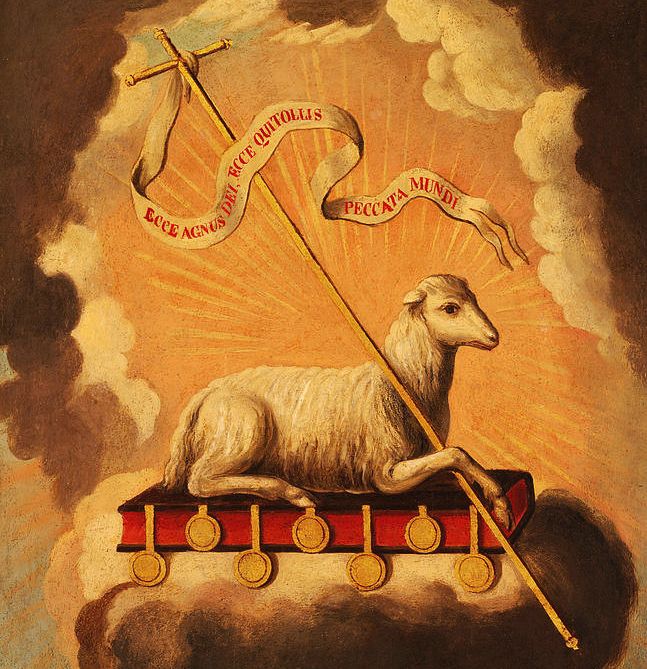

If similarly finished, the Llandderfel effigy would have blazed with colour on feast days, intensifying its catechetical presence in procession. Most striking is the seated or recumbent posture. Horses in devotional and civic imagery are typically depicted in motion—a seated animal belongs to a different iconographic register, such as peace, offering, or enthronement. In medieval art, the resting Agnus Dei, and in some contexts the contemplative or paradisal Stag, signal completed sacrifice and victorious rest. The posture here is a theological clue, not a mere convenience.

Why the Hollow Body?

The deep cavity in the torso is decisive. In Catholic practice, hollowed cavities in sacred objects almost invariably indicate a reliquary function. Altars are consecrated only when they contain relics in a sepulcrum (Pontificale Romanum, De Ecclesiae Consecratione, cap.12) and the Council of Trent reaffirmed the placement of relics at the altar (Session XXII, De Sacrificio Missae, ch.4). Portable altars, crucifixes, and processional statues frequently incorporate reliquary chambers—some of the most venerated medieval treasures.

“True Cross fragments, the Crown of Thorns, and Holy Blood—were housed in hollow receptacles made to be seen, kissed, and carried” (Patrick J. Geary, Furta Sacra, 1990).

Large hollow devotional objects were common across Europe. Reliquary busts at Aachen, the gilded statue-shrine of St Foy at Conques, and the massive chasse of St Taurin at Évreux were designed for solemn translation and ostension. The Llandderfel figure—with its sturdy oak shell and central cavity—clearly belongs to this family of moving shrines. Closer to home, Anglo-Welsh practice offers strong parallels.

“St Cuthbert’s coffin, a reliquary built for transport, was repeatedly borne by the community during Viking raids and plague” (David Rollason, Saint Cuthbert and His Community to A.D. 1200, 1989).

St Winefride’s shrine at Holywell was the focus of translations and displayed on feast days, drawing pilgrims from across. Parish-scale feretories were routinely brought out at Rogationtide and on major festivals. The Llandderfel effigy most plausibly carried a relic of St Derfel or a universal relic such as the True Cross, making it a portable locus of grace.

Horse, Stag, or Lamb? Reassessing the Iconography

Tradition calls the figure Cefyl Derfel—Derfel’s Horse—because Welsh ceffyl derives from Latin caballus and unambiguously means “horse” (philologically parallel to French cheval) rather than “stag” (French cerf from Latin cervus). The name preserves a perception of equine function in the late medieval or post-Reformation mind, but it does not settle the original iconography. On close inspection, the carving lacks decisive equine traits; the head’s vertical taper, the drilled sockets that could once have supported detachable antlers, and—most telling—the seated pose, all tilt towards a cervid identification.

In medieval bestiaries and the Physiologus, the Stag tramples serpents, seeks the spring, and renews itself by shedding antlers—allegories of Christ’s victory over Satan, baptismal life, and Resurrection (Physiologus, ch.26).

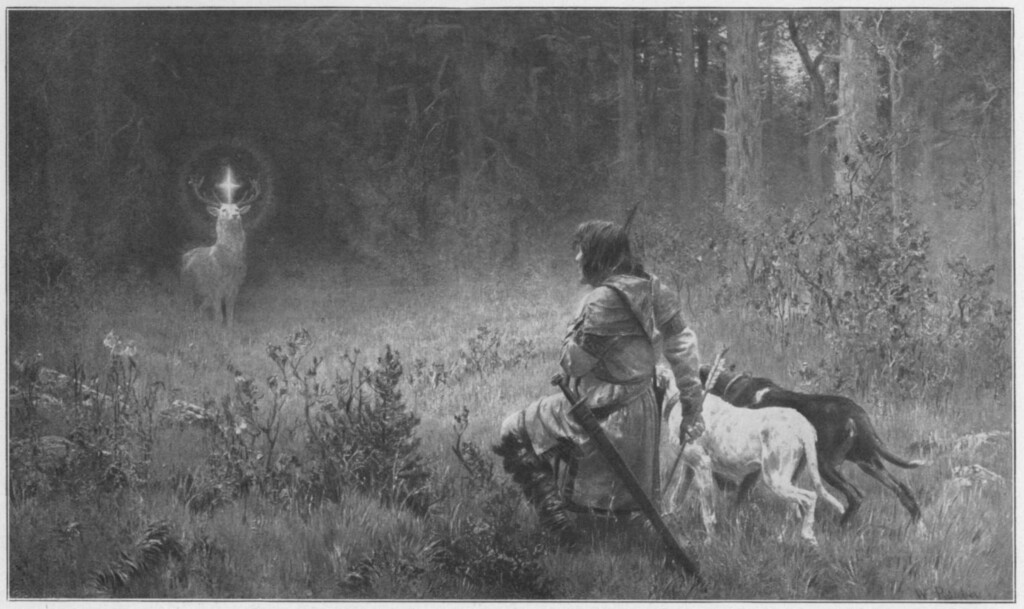

Hagiography goes further: in the vitae of Saint Hubert and Saint Eustace, the Stag appears with a radiant crucifix between its antlers as Christ Himself, calling the hunter to repentance and conversion.

Saint Edern and the Breton Tradition

Saint Derfel’s Stag would not have stood alone in this symbolism. The legend of Saint Edern in Brittany tells how a hunted stag fled under his cloak and was spared thereafter, becoming tame and following him. In some versions, Edern rode the Stag by night to trace the boundaries of the land he was to Christianise. Breton iconography preserves this duality: in Plouedern, Edern stands with a crouching stag at his side—emblem of nature subdued—in Lannédern, he is mounted, claiming the landscape for Christ. Derfel’s crouching, yet processional Stag therefore participates in a wider tradition in which the saint and the animal together signify a Christianising mission and a dominion over creation healed through grace.

Paschal Lamb Possibility

A complementary reading sees the figure as an Agnus Dei. Its Eastertide use, seated posture, and hollow cavity resonate with medieval Paschal Lamb imagery, and there are continental precedents for processional figures or monstrances that integrate the Lamb of God symbolically into Corpus Christi and Easter rites. Caution is warranted: there is no direct evidence of large wooden Paschal Lamb effigies in Wales, and such figures are rare generally. Yet, the theology aligns, and medieval imagery was often polyvalent—lamb and stag readings can coexist.

The White Stag of Easter

Bringing these strands together, the most compelling synthesis is to read the Llandderfel effigy as the White Stag of Easter. In Arthurian romance—from Chrétien de Troyes’ Erec et Enide to episodes in the Mabinogion—the White Stag inaugurates a quest that tests and purifies the knight. In Catholic devotion, the White Stag, also known as The White Heart, is Christ: the theophany who summons, the victor who tramples the serpent, the guide who leads to living waters. Brought out at Easter, seated in triumph and bearing a relic, the Llandderfel figure bridges Derfel’s Arthurian past and his monastic present: the warrior who has “found” the White Stag becomes the monk who leads his people into the joy of Resurrection.

Patristic Commentary deepens this meaning, Psalm 42: “As the deer longs for streams of water” was sung over catechumens and at funerals.

Augustine and Jerome saw the Stag as the catechumen thirsting for baptism, who first kills the serpent (vice) and then runs to the font to purge the poison. Medieval theology mapped a spiritual ascent: penitence (devour the serpent), baptism (drink), growth in virtue (shed antlers of pride), contemplation (ascend the mountains), and death in Christ (funerary Psalm).

Origen interprets the leaping Stag in Song of Songs 2:8–9 as Christ Himself, who “comes leaping on the mountains”—the prophets, apostles, and saints—to bring salvation. Hildegard of Bingen sees the Stag’s renewed antlers as a sign of spiritual rebirth and its thirst as the soul’s longing for God. Thus, the Llandderfel stag is a sermon in wood, leading pilgrims step by step from conversion to contemplation and finally to the hope of eternal life.

Processions and Ritual Drama in Medieval Wales

The effigy was not static. Sources indicate it was carried in processions, most likely at Eastertide and on Derfel’s wake day, aligning with the medieval pattern of blessing and exorcistic rites in the agricultural year. Rogationtide perambulations blessed boundaries and fields.

“Easter celebrations dramatised the Harrowing of Hell and the triumph of life over death” (Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars, 1992).

Continental analogues include ritualised combats with dragons or their drowning in French processions, and the parading of the Risen Christ in Central Europe. At Llandderfel, the paired images of Derfel and his animal companion enacted hunting scenes on Bryn Derfel, fusing liturgy and legend—the hollowed figure likely carrying a relic—served as a portable sermon of victory and intercession. Even after iconoclasm, memory of festive use persisted. In the eighteenth century, the figure was still carried out on Easter Tuesday to a nearby field and used as a makeshift fairground ride. This remarkable folk remnant keeps the Easter association alive even as doctrine fell from popular memory.

Christianisation of Folk Tradition

By the time of Derfel and Edern, there was no living memory of Cernunnos or any stag-god in Britain. Christianity had already absorbed rural sacred places into its own symbolic universe: wells were blessed, stones carved with crosses, groves turned into hermitages. The medieval Church preserved and baptised the countryside’s memory—it did not erase it. Modern Wiccan and neo-pagan readings that treat Derfel’s Stag as a relic of horned-god worship impose a nineteenth-century fantasy onto a thoroughly Christian landscape. Medieval people understood the Stag biblically and liturgically—as Christ, as the catechumen, as the saint’s companion—not as a survival of paganism.

Ffynnon Dderfel: The Well and its Memory

Accounts of customs at Ffynnon Dderfel, on Garth y Llan above the village, are lengthy and sometimes fantastical, yet the well’s specific role is either modest or largely forgotten.

Lhuyd notes “Ffynnon Derfel on Garth y Llan close to the church” (Lhuyd, Parochialia, c.1698).

A Royal Commission visit in June 1913 described only a small, slab-covered spring forming a 4-foot reservoir—hardly suited to adult bathing or elaborate votive offerings—and suggested that the original watercourse may have shifted. Nineteenth-century reports mention earthen pipes between the spring and a supposed priory site beside the Church, and a local toponym survives as Maes y Priordy.

“Yet, a 1990s evaluation found no archaeological evidence for a priory and no documentary proof that it ever existed” (Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, Safle’r Priordy, Llandderfel, c.1992; R. Jennings, “Llandderfel Parochialia”, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1861).

The well thus appears as a peripheral memory within a broader pilgrimage landscape centred on image, relic, procession, and the saint’s intercession.

Arthurian Context and Plantagenet Use

Derfel and Edern were folded into the Arthurian mythos as knights or contemporaries of Arthur who became saints. Monastic chroniclers used this to Christianise the heroic past. In the twelfth–thirteenth centuries, Arthur’s story was reshaped by Geoffrey of Monmouth and Chrétien de Troyes into a Christian epic, deliberately promoted by the Angevin/Plantagenet court as a rival to the Capetian cult of Charlemagne. The Grail cycle turned the Round Table into a Eucharistic fellowship—Arthur became the Christian king par excellence. The cult of the Saints, such as Derfel’s, anchored this ideology in local devotion: pilgrimage became a way to participate in Arthur’s Christian Britain.

Reformation Suppression and the Modern Revival

Henrician Injunctions in 1536 and 1538 targeted “feigned images and pilgrimages”, and Edward VI’s reforms abolished processions and drama, ordering the destruction of images, shrines, candles, and wax trindles.

“Price’s 1538 removal of Derfel’s figure—despite a £40 offer to keep it—and its notorious use at the execution of Friar Forest exemplify the ideological theatre of repression” (Thomas, 1874).

By contrast, in France, Spain, and Catholic Germany, Rogationtide, Corpus Christi, and the feasts of the saints continued, preserving their visual and theological richness. In the twentieth century, England began to rediscover this Roman Catholic heritage. The York Mystery Plays were revived in 1951 and now run on a five-year cycle—the Chester Mystery Plays and Coventry’s Shearmen and Tailors’ Pageant have also returned, offering modern audiences a window into the sacramental world of medieval Theatre. In Scotland, there is a legend about King David I of Scotland, who was hunting in Holyrood Park below Arthur’s Seat and encountered a mysterious white stag that charged at him. Instead of a threat, the stag appeared to be a sign from God. That night, it was said, St Andrew spoke to him in a dream, telling him to build a church there to house the Black Rood (an ornate and bejewelled golden cross-shaped reliquary containing a supposed piece of the True Cross). Prompting the king to establish an abbey on the site and to become more pious.

Historiographical Note

Protestant historians such as John Foxe and John Strype framed the suppression as a victory over “papistical darkness”, re-educating generations to view images, relics, and processions as superstition (Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1563). Revisionist scholarship—preeminently Eamon Duffy and Christopher Haigh—has recast the Reformation as a cultural rupture that amputated a shared ritual language and devastated lay devotion (Duffy, 1992; Haigh, English Reformations, 1993).

The long consequence has been confusion: many today—including neo-pagan groups—misread Roman Catholic rural survivals. In fact, as shown in Templarkey magazine, “Witchcraft Special Edition” Issue 8 (July 2023), charms, holy-well rites, and seasonal customs were thoroughly Roman Catholic Christian, woven into the liturgical year (Templarkey, 2023).

Why It Matters Today: Wiccan Misinterpretations and Cultural Re-Education

Reviving processions, Rogationtide blessings, and “Mystery Plays” is not heritage tourism but cultural repair. Such rites reconnect society with the theological vision that once united doctrine, art, and action. Read in its original key, the Llandderfel effigy is not a quaint relic but a proclamation of the Gospel in wood, challenging present communities to recover ritual literacy and to receive the White Stag of Easter as Christ triumphant.

Conclusion: A Theology in Wood

The so-called “horse of St Derfel” may, in fact, be the White Stag of Easter—Christ enthroned in oak, resting after the Passion, trampling the serpent, calling the faithful to the fountain of life. Its hollow body, seated posture, and Eastertide use situate it within Europe’s reliquary and processional tradition while giving it a distinctly Welsh voice that bridges Arthurian legend and monastic piety. Today, the figure still rests in the porch at Llandderfel, one of the very few surviving large-scale wooden devotional objects of pre-Reformation Wales. To stand before it is to encounter a living catechesis—an enacted theology of death, resurrection, and renewal. Far from superstition, it remains a homily in timber, still capable of instructing and inspiring.

Epilogue: The Reformation and the Breaking of the Cult

The Reformation shattered this religious world. In 1538, Cromwell’s commissioner Ellis Price removed the figure of Saint Derfel from Llandderfel to London, using it as the wooden stake to execute by burning the Jesuit priest John Forest. Wells were closed, statues smashed, screens and wall paintings stripped. The countryside, once dotted with Christianised holy places, was forcibly desacralised. Ironically, because the reformers left behind what they thought was a mere beast, Derfel’s Stag survived—battered but enduring, a witness to the lost devotional ecology of medieval Wales. Today, its survival allows us to recover not only an object of wood but an entire vision of Christian sanctity, where saints, animals, land, and people were bound together under the sign of the Cross.

Bibliography:

Primary/medieval and early sources:

Albert Le Grand, Les Vies des Saints de la Bretagne Armorique (Nantes: 1637; many later eds.).

Bonedd y Saint, in P.C. Bartrum (ed.), Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1966).

Chrétien de Troyes, Erec et Enide, ed. & trans. Carleton W. Carroll (New York: Garland, 1987).

Foxe, John, Acts and Monuments (London: 1563).

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae, ed. Michael D. Reeve; trans. Neil Wright (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007).

Physiologus, trans. Michael J. Curley (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979).

The Mabinogion, trans. Sioned Davies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Patristic and medieval theological:

Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos, CCSL 38–40 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1956–7).

Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, trans. Columba Hart & Jane Bishop (New York: Paulist Press, 1990).

Jerome, Tractatus in Psalmos (various eds.; for Psalm 41/42 Commentary).

Origen, Commentary on the Song of Songs, trans. R.P. Lawson (New York/Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1957).

Studies, references, and modern works:

Baring-Gould, Sabine, & Fisher, John, Lives of the British Saints, vol.2 (London: 1908).

Bray, Gerald (ed.), Documents of the English Reformation (Cambridge: James Clarke, 1994).

Duffy, Eamon, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400–1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Forsyth, Ilene H., The Throne of Wisdom: Wood Sculptures of the Madonna in Romanesque France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972).

Geary, Patrick J., Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Gray, Madeleine, research on St Derfel’s Stag and processional usage (unpublished notes/lectures, cited herein).

Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, Report on the Archaeological Evaluation at Safle’r Priordy, Llandderfel (c.1992).

Haigh, Christopher, English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society under the Tudors (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993).

Hahn, Cynthia, Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400–c.1204 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012).

Hurlock, Kathryn, Medieval Welsh Pilgrimage c.1100–1500 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Jennings, R., “Llandderfel Parochialia”, Archaeologia Cambrensis (1861), 76.

Johnston, Alexandra F., “The York Cycle and Its Revivals”, in Richard Beadle & Alan J. Fletcher (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 217–233.

Lhuyd, Edward, Parochialia (c.1698), National Library of Wales MS.

Pennant, Thomas, Tours in Wales, vol.2 (London, 1781), 213–214.

RCAHMW, Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire: Volume VI—Merioneth (London: HMSO, 1921).

Rollason, David, Saint Cuthbert and His Community to A.D. 1200 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1989).

Templarkey magazine, “Witchcraft Special Edition” Issue 8: (July 2023).

Thomas, D.H., A History of the Diocese of St Asaph (Oswestry: Caxton Press, 1874).

Wyn Evans, J., “The Cult of St Winefride in the Middle Ages”, in Jennifer O’Reilly (ed.), Saints and Their Cults in the Atlantic World (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2010), 61–76.