Mary the Magdalene and the Holy Grail: The First Grail Maiden and the Magnificat

This article explores the meaning behind depictions of Mary with the Grail in churches such as Sant Climent de Taüll, examining their apse frescoes, iconography, theology, and the Grail myths associated with them. We will divulge far more than the books The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail by Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, the da Vinci Code by Dan Brown, and the Bloodline theory created by the Priory of Sion and Pierre Platard.

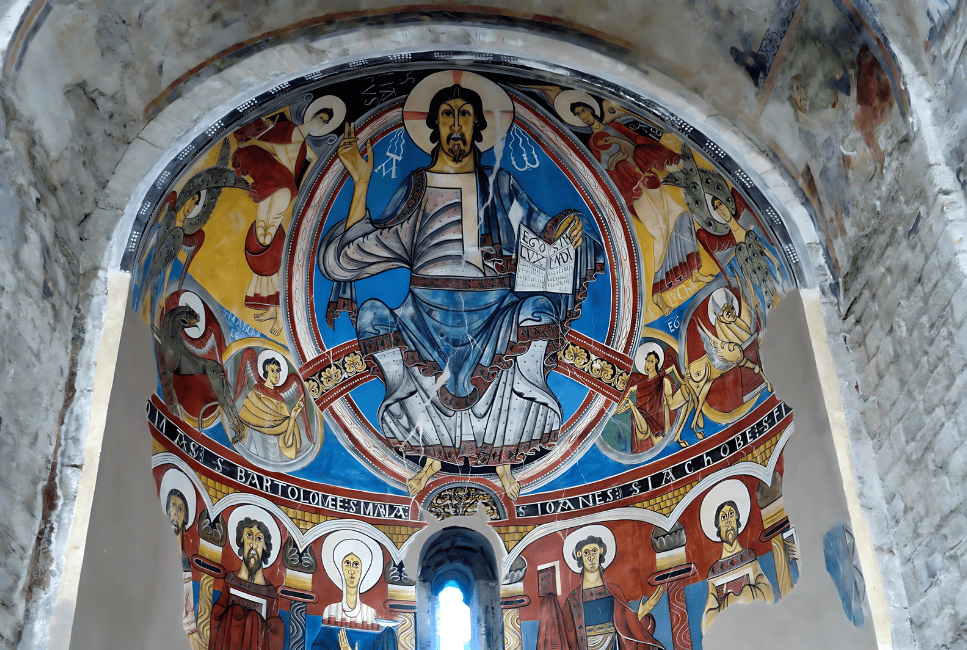

The Apse Fresco of Sant Climent de Taüll; The First Apostle Mary

Consecrated in 1123, the apse fresco of the early Church of Sant Climent de Taüll stands as a monumental testament to Romanesque art’s intellectual and spiritual ambitions. Created by the enigmatic Master of Taüll, it is a visual symphony that blends celestial visions with theological precision. In modern times, however, reinterpretations—especially concerning the figure of the Virgin Mary as a physical chalice has layered anachronistic Grail legends onto the fresco’s original theological intent.

To untangle this complex interplay of art, theology, and myth, we delve into the symbolic language of Romanesque iconography. This approach reveals the fresco’s eschatological meaning and precise sacramental significance, steering clear of retrospective narratives.

Christ Pantocrator: Sovereign of Time and Space

At the highest point of the apse, Christ Pantocrator is seated regally within a luminous mandorla, embodying cosmic authority and omnipotence. Known as “Christ in Majesty,” this depiction shows Christ not merely observing the world but reigning over it, enshrined in an eternal present that transcends temporal boundaries.

Surrounding Christ are the four tetramorphic Evangelists, symbolic messengers of the divine word: the lion for Mark, the ox for Luke, the eagle for John, and the angel for Matthew.

Drawing from the apocalyptic imagery of the Book of Revelation and Ezekiel’s visions, this underscores Christ’s role not only as Redeemer but as the eschaton—the end and fulfilment of time. Kenneth John Conant, in Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture (1993), traces the rise of such Christological motifs to the Carolingian Renaissance, where apocalyptic visions became central to ecclesiastical art and theology.

The Master of Taüll’s dynamic composition—his use of vibrant blues and reds and the fluidity of drapery—marks a significant evolution in Romanesque art. It blends the static frontality of Byzantine iconography with a newfound emphasis on movement and emotion. The use of the rare aerinite pigment for Christ’s robe not only showcases the artist’s technical prowess but also serves as a material manifestation of divine grandeur, as Walter Cahn discusses in Romanesque Bible Illumination (1982).

The Virgin Mary and the Holy Grail Vessel: A Eucharistic Symbol

Beneath the imposing figure of Christ Pantocrator, the Virgin Mary holds a vessel (chalice of Magdalene) from which rays of red light emanate. Modern interpretations, influenced by the allure of Holy Grail legends, have often misconstrued this image as an early depiction of the Grail. However, this vessel is far more than a legendary relic; it is a profound Eucharistic symbol capturing the theological essence of medieval sacramental life.

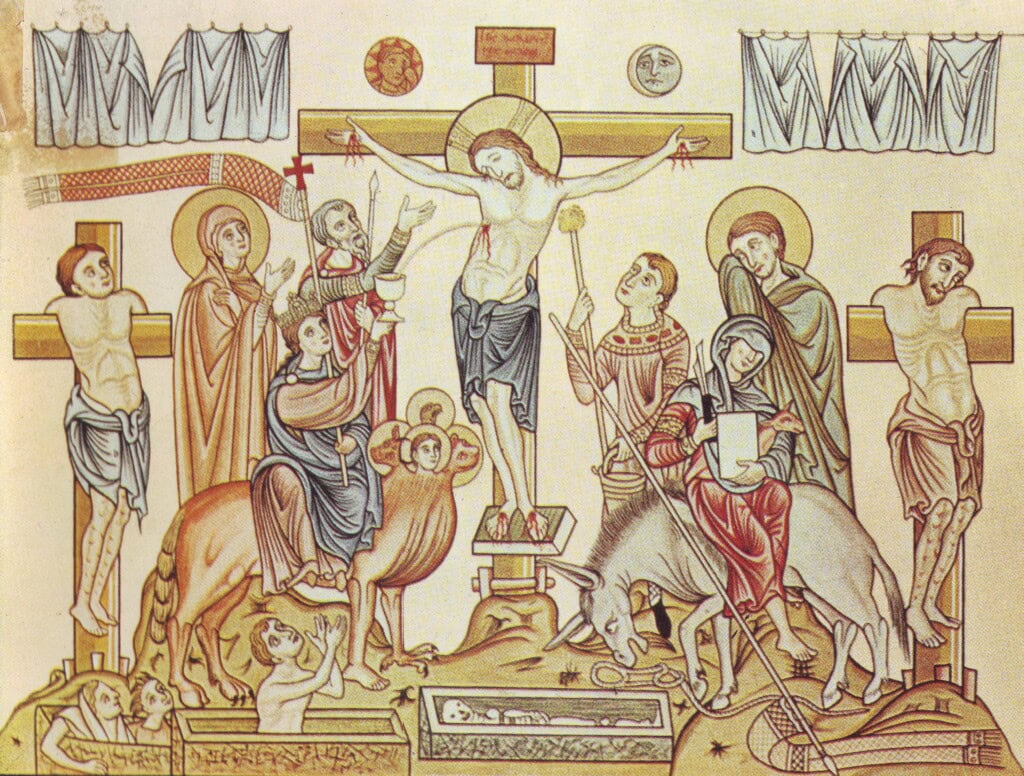

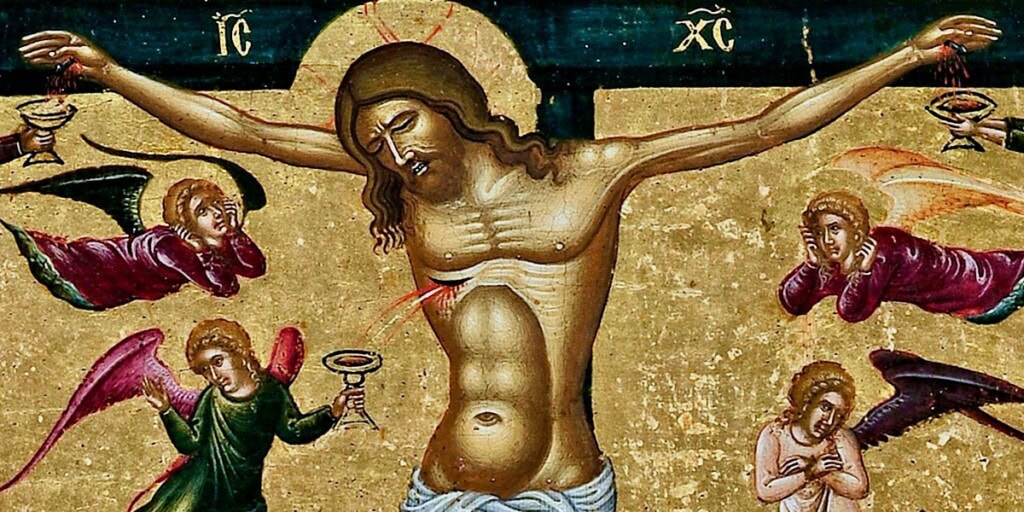

This symbolism traces back to representations of Christus Patiens, the suffering Christ, where His crucified body releases both water and blood as a Roman soldier pierces His side. These two streams signify the dual sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist. In medieval depictions, these sacred fluids are often collected by a figure identifiable as Ecclesia—the allegorical representation of the Church—who holds a chalice to gather Christ’s blood.

While the fresco at Sant Climent de Taüll does not directly portray the crucified Christ, it evokes this sacramental imagery. Holding the sacred vessel—that held the blood of Christ—Mary stands in for Ecclesia, gathering Christ’s blood not as a relic but as a manifestation of the Church’s role in administering the Eucharist. Miri Rubin’s Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary (2009) and Marina Warner’s Alone of All Her Sex (2013) emphasize that Mary’s role as an intercessor was deeply tied to her participation in these sacred mysteries long before any Grail legends emerged.

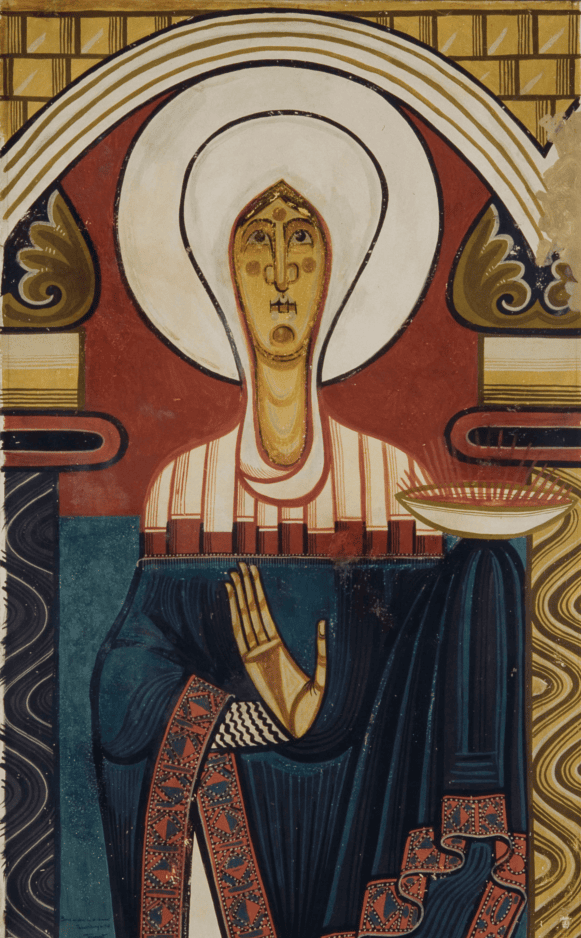

The Sacramentary of Drogo

The Sacramentary of Drogo offers an explicit connection between Mary and the Eucharistic chalice. In this 9th-century liturgical manuscript, Mary is depicted holding the Holy Chalice, prefiguring her role in the Church’s sacramental life. This image underscores a deeper understanding of Mary as both the Mother of Christ and the symbolic “Mother of the Church,” who gathers and offers Christ’s blood for the salvation of all.

Marian Imagery in Romanesque and Gothic Art

Depictions of Mary holding a vessel, often symbolizing the Eucharist, recur in Romanesque and Gothic religious art. Across various churches, this iconography reinforces her role as an intermediary and protector of the faithful, grounded in sacramental theology rather than mystical Grail legends. Notable examples include:

- Santa Maria de Mur (Catalonia, Spain): Mary is depicted holding a symbolic object, reinforcing her association with divine grace. Though not linked to the Grail, the vessel represents her role in spiritually nourishing the faithful through the Eucharistic sacrifice.

- Sant Joan de Boí (Catalonia, Spain): Similar to the frescoes in Sant Climent, Mary occupies a position of spiritual prominence. While she is not depicted holding a vessel, her elevated role among the apostles underscores her importance as a divine mediator in the Romanesque tradition.

- Chartres Cathedral (France): The cathedral’s Marian representations, particularly in its stained glass and sculptures, show Mary holding objects such as a book or a vessel associated with wisdom and divine grace. Though not connected to the Grail, these images emphasize her cosmic role as Theotokos, the bearer of God, and her intimate link to Eucharistic symbolism.

- Notre-Dame la Grande (Poitiers, France): Portal sculptures depict Mary enthroned and holding Christ. Some interpretations suggest she holds a symbolic vessel connected to themes of salvation and divine grace, reinforcing her spiritual role within the Church.

- Sant Pere del Burgal (Catalonia, Spain): The frescoes place Mary in a sacred, intercessory role, close to Christ and the apostles. Although she does not hold a vessel here, the theological undertones focus on her as a mediator of divine grace, reflecting the sacramental life of the medieval Church.

- Iglesia de Santa Eugenia (Argolell, Catalonia, Spain): Similar to Sant Climent, the frescoes depict Mary in an intercessory role, emphasizing her importance in the spiritual life of the faithful. The image below shows the fresco from the apse of Santa Eulàlia d’Estaon, Spain. Saint Eulalia is on the left, and the Virgin Mary is on the right, holding the Euceristic Grail.

Ecclesia and Synagoga: Symbols of Spiritual Transition

In medieval Europe’s theological and artistic landscape, Ecclesia and Synagoga represent contrasting figures. Ecclesia symbolizes the triumphant Church, enlightened by the new covenant in Christ’s blood, while Synagoga represents the old law, veiled and incomplete. These figures, often depicted as two women—Ecclesia crowned and holding a chalice, Synagoga blindfolded and clutching the tablets of the law—encapsulate the theological transition from Judaism to Christianity. This contrast illustrates not a repudiation but a fulfilment of the old through the new.

In the fresco at Sant Climent de Taüll, while Synagoga is not explicitly depicted, Mary’s positioning as she holds the vessel underscores her role as Ecclesia—the embodiment of the Church and the living vessel of divine grace. By gathering Christ’s blood, she symbolizes the Church’s custodianship of the Eucharist, a role later mystically connected with the legend of the Holy Grail.

Mary and John at the Foot of the Cross: Eucharistic Significance

The placement of Mary and John in the fresco mirrors their positions at the foot of the cross, infusing the composition with deeper Eucharistic meaning. In Christian tradition, Mary and John are the two figures present at Christ’s crucifixion, witnesses to the outpouring of His sacrificial blood. Their symbolic positioning in the fresco connects directly to the Eucharist.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus entrusts His mother to the care of the disciples, establishing a new spiritual family. This scene is rich with Eucharistic overtones, as the blood and water flowing from Christ’s side become the sacramental foundation of the Church. The depiction of Mary (Sancta Maria) and John (Sanctus Ioannes) in the Sant Climent fresco reflects this moment, where witnessing becomes an act of receiving the sacrament. Rubin and Warner highlight that Mary, as the mother of the Church, symbolically gathers Christ’s blood before Joseph of Arimathea enters the legend, reinforcing her primordial role in the salvation narrative.

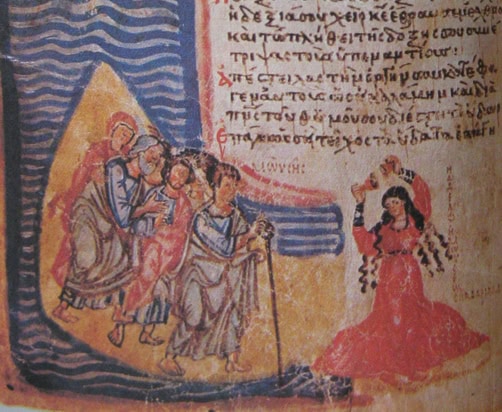

The Evolution of the Grail Legend and King Arthur

Later medieval Grail legends, centring on Joseph of Arimathea collecting Christ’s blood, signify a shift in interpreting these sacramental symbols. Initially, it is Mary—not Joseph—who gathers Christ’s blood, representing Ecclesia, the Church. However, as Arthurian romances gained popularity, particularly with the French poet Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval and Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie, the narrative was altered to fit the chivalric ethos of the time.

Joseph of Arimathea, once a peripheral figure in the Gospels, became the mystical custodian of the Grail—a transformation symbolizing the medieval knight’s journey toward Christian conversion. Notably, the Bible does not mention Mary or Joseph collecting Christ’s blood. Joseph’s role is limited to requesting Jesus’ body from Pilate and placing it in his own tomb, while Mary’s presence at the crucifixion is significant but does not involve gathering His blood.

In The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol (1991), Roger Sherman Loomis traces this evolution, showing how Eucharistic themes inherent in early Christian art and theology were repurposed to create a chivalric ideal. The Grail became a quest object—a mystical chalice granting divine grace to the worthy.

The Holy Grail in History and Legend

Throughout Christianity’s history, the Holy Grail has endured as a complex and elusive symbol. Early Christian writings offer no evidence that the cup used at the Last Supper survived or was preserved as a relic. In its original context, the Grail was seen as a metaphor for salvation—a symbol, not an object. However, during the 12th and 13th centuries, it transformed into a focal point for spiritual quests, a transformation reignited during the Romantic period in the 19th century.

Richard Barber’s The Holy Grail (2004) traces the metamorphosis of the Grail legend, exploring how biblical and apocryphal traditions were reshaped into a medieval symbol of redemption. The earliest documented interest in the relic comes from the 7th-century writings of Arculf, a Frankish bishop who claimed to have seen the sacred chalice in Jerusalem. However, no historical evidence supports the existence of this artefact.

The term “Grail” first appeared in the unfinished romance Perceval (1190) by Chrétien de Troyes, featuring a mysterious procession with a gem-encrusted dish serving the host to ailing figures. The Grail was not yet explicitly tied to the Last Supper. Elements like a bleeding lance—possibly referencing the spear that pierced Christ’s side—suggest that early writers were beginning to fuse the Grail with relics of the Passion.

Robert de Boron’s L’Estoire dou Graal was the first to explicitly identify the Grail as the vessel from the Last Supper. His story recounts how Joseph of Arimathea collects Christ’s blood in the Grail after the crucifixion—a detail absent from biblical texts but rooted in apocryphal traditions.

These medieval stories transformed the Grail into a theological symbol representing the body and blood of Christ, intertwining with the Eucharist’s mysteries. This connection is underscored by recurring imagery in liturgical manuscripts, such as the Sacramentary of Drogon, where Mary is shown holding the Grail, prefiguring her role as Ecclesia.

Graalophore: The Grail Bearer as Symbol of the Church

“Graalophore” is a term combining “Graal” (Grail) and “-phore” (from the Greek “phoros,” meaning “bearer” or “carrier”), used to describe the symbolic figure bearing the Holy Grail, often identified with the Church (Ecclesia) in medieval symbolism.

Maurice Vloberg, in L’Eucharistie (vol. 1), states:

“The bearer of the Grail—let us call her the Graalophore—is unmistakably a figure representing the Church.”

This symbol often appears as a noblewoman, sometimes crowned or haloed, embodying the New Law and standing in opposition to Synagoga, symbolizing the Old Law. This majestic woman gathers the blood of Christ’s Passion in a chalice—an image prevalent in medieval Western art.

Mario Roques, in his study of the Hortus deliciarum, emphasizes that:

“Ecclesia has gathered the blood that creates her very being and defines her eternal mission, and she eternally bears the vessel that contains it.”

Therefore, this underscores the Church’s primary vocation—the celebration of the Eucharistic rite and the sacramental life of grace.

An ancient fresco from Bawit in Upper Egypt depicts a haloed and crowned woman holding a large chalice upon her chest, with the Greek inscription Hagia Ecclesia (“Holy Church”). This iconography shows the long-standing tradition of associating the Church with the sacred vessel, predating and later merging into Western medieval Grail legends.

The Virgin Orans

In the apse vault at Estamariu—Sant Vicenç d’Estamariu—the figure of the Virgin Orans takes centre stage in a symbolic gesture deeply rooted in early Christian and Roman iconography.

The Orans pose—hands raised in prayer—represents the soul in a state of devotion and intercession, bridging humanity with the divine. “One who is praying or pleading”; also orant or orante. Lifting holy hands is a posture or bodily attitude of prayer, usually standing, with the elbows close to the sides of the body with the hands outstretched sideways and palms up. In Romanesque art, this figure symbolizes the Church, a maternal presence embodying prayer and protection for the faithful. Positioned among the apostles, the Virgin Orans signifies the Church’s continuous mediation between Christ and the earthly realm.

This iconographic tradition elevates her presence beyond mere representation, embodying the Church’s timeless prayer for salvation and sanctity. When interpreted as the Virgin Mary, the Orans figure adds a layer of Marian devotion, highlighting her role as the spiritual mother of the Church and emphasizing her significance in Romanesque theological and artistic expressions.

Conclusion: Romanesque Origins, Ecclesia and Synagoga and the Midrashic and Kabbalistic Symbolism

In its original Romanesque context, the apse fresco of Sant Climent de Taüll is far removed from later Grail legends and chivalric romance. It is a visual testament to the Church’s sacramental heart, where Mary, as Ecclesia, gathers Christ’s blood in a vessel signifying the Eucharist—not a mythical relic. Understanding the fresco within its theological and artistic framework allows us to appreciate it as a profound meditation on the mysteries of faith, predating and transcending the legends of medieval knights and their quests.

Rather than serving as a precursor to Grail lore, the Sant Climent de Taüll fresco is a visual articulation of the Church’s sacramental theology. Its symbolism is rooted in cosmic and Eucharistic reality, with Mary—in her role as Ecclesia—standing at the intersection of divine grace and human devotion. The later introduction of Joseph of Arimathea and the Grail legends were shaped by the chivalric and romantic currents of medieval Europe, diverging from the original theological grounding.

By returning to the fresco’s Romanesque origins, we dispel myths and appreciate its true spiritual resonance. It is a work not of secret relics or mythical quests but of Christ’s omnipotence, the sacrificial blood that redeems, and Mary’s enduring role as the vessel of divine grace. The medieval faithful found meaning in the apocalyptic Christ, the suffering Savior, and the Eucharistic sacrifice that nourished the very heart of the Church.

Thus, Sant Climent de Taüll invites us to look beyond legends into the deep well of Romanesque theology—a time when art, faith, and sacrament formed an unbroken chain from the altar to the heavens, binding the believer to the divine.

Ecclesia and Synagoga

In medieval Christian art, the symbolic contrast between Ecclesia and Synagoga illustrates the theological transition from the Old to the New Covenant. Ecclesia, representing the Christian Church, is often portrayed as a crowned woman carrying a chalice or cross—signifying triumph and the New Law. In contrast, Synagoga symbolizes Judaism, usually depicted blindfolded and holding broken law tablets or a bent staff, reflecting the perceived obsolescence of the Old Law. This imagery reinforces Christian theological beliefs about the supremacy of the Church and the Eucharist.

The depiction of Ecclesia and Synagoga is central to understanding the theological landscape in which the Grail legend emerged. The triumph of Ecclesia over Synagoga mirrors the triumph of the New Covenant over the Old—a motif deeply intertwined with the Grail’s Eucharistic symbolism. As the vessel of Christ’s blood, the Grail embodies the Church’s sacred mission to carry forward the sacramental life, ensuring salvation through the Eucharist. Thus, far from being a mere relic, the Grail legend serves as an allegory for the Church’s eternal role as the bearer of divine grace.

The Five Cups of the Seder and Kabbalistic Symbolism: Linking Mary, the Grail, and the Divine Feminine

The rich tapestry of Judeo-Christian traditions offers profound connections between the Passover Seder rituals, Kabbalistic teachings, and the iconography of Mary holding a vessel in Romanesque art. By exploring these links, we gain deeper insights into the symbolic significance of Mary as the Grail bearer and her representation of divine wisdom and redemption.

The Five Cups of the Seder: Messianic Hope and the Divine Feminine

During the Jewish Passover Seder, participants traditionally drink four cups of wine, each symbolizing a promise of deliverance that God made to the Israelites in the Book of Exodus (6:6–7):

- The First Cup – Sanctification (Kiddush): “I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians.”

- The Second Cup – Deliverance: “I will rescue you from their bondage.”

- The Third Cup – Redemption: “I will redeem you with an outstretched arm.”

- The Fourth Cup – Acceptance: “I will take you as My people.”

However, some traditions introduce a Fifth Cup—known as Elijah’s Cup—which is poured but not consumed. This cup symbolizes the future redemption and the coming of the Messiah, with Elijah the Prophet heralding this anticipated era. The act of opening the door for Elijah during the Seder expresses hope and readiness for spiritual fulfilment.

In addition, some communities include the Cup of Miriam, which is filled with water instead of wine. Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron, is celebrated for her leadership and the miraculous Well of Miriam that provided sustenance to the Israelites in the desert. This cup honours the feminine aspect of divine providence and the nurturing qualities associated with Miriam.

Kabbalistic Symbolism: Wine as Binah and Malkuth

Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition—delves into the nature of the Divine through the concept of the Sephirot—ten attributes or emanations of God that manifest in the world. Wine and water hold significant symbolic meanings within this framework—particularly relating to the Sephirot of Binah and Malkuth.

Binah (Understanding):

– Position: The third Sephirah on the Tree of Life.

– Symbolism: Represents intuitive understanding, contemplation, and the Divine Feminine aspect. It is the womb where ideas conceived in Chokhmah (Wisdom) are developed and given form.

– Association with Wine: Wine has the capacity to reveal hidden truths and bring joy, paralleling Binah’s role in unveiling divine mysteries and deep understanding.

Malkuth (Kingdom):

– Position: The tenth and final Sephirah.

– Symbolism: Embodies the physical world and the manifestation of all preceding divine energies into tangible reality.

– Association with Water: Water signifies purity, life, and the flow of blessings into the material realm, aligning with Malkuth’s role in grounding spiritual concepts into everyday existence.

During the Seder, the consumption of wine symbolizes the absorption of divine wisdom (Binah)—while the inclusion of water (as in Miriam’s Cup) represents the manifestation of this wisdom in the physical world (Malkuth). The blending of wine and water in some traditions reflects the harmonious integration of these spiritual principles.

During the Seder, the consumption of wine symbolizes the absorption of divine wisdom (Binah)—while the inclusion of water (as in Miriam’s Cup) represents the manifestation of this wisdom in the physical world (Malkuth). The blending of wine and water in some traditions reflects the harmonious integration of these spiritual principles.

Connecting Mary, the Grail, and Kabbalistic Themes

The integration of these Jewish traditions and Kabbalistic concepts offers a fresh perspective on the depiction of Mary holding a vessel in the frescoes of Sant Climent de Taüll and similar Romanesque art. Mary can be seen as embodying both Binah and Malkuth:

As Binah:

– Mary represents the Divine Feminine and the mother of divine wisdom, nurturing and giving form to the Word (Logos) made flesh.

– Holding the vessel, she symbolizes the unveiling of divine mysteries and the deep understanding necessary for spiritual redemption.

As Malkuth:

– She embodies the physical manifestation of divine grace, bringing forth the Savior into the world.

– The vessel signifies the channel through which divine blessings flow into the material realm, aligning with her role as the mediator between heaven and earth.

Furthermore, the Graalophore—the Grail bearer—is a symbol of the Church (Ecclesia) as the custodian of divine grace. Mary’s depiction as holding the vessel parallels the Church’s role in administering the sacraments and sustaining the spiritual life of the faithful.

Wine, Water, and the Dual Nature of Christ’s Sacrifice

The Christian narrative of blood and water flowing from Jesus’ side during the Crucifixion (John 19:34) resonates with the themes of wine and water in the Seder and Kabbalistic symbolism:

Blood (Wine):

– Represents the new covenant and the sacrificial redemption offered through Christ.

– Aligns with the wine of the Seder, symbolizing joy, liberation, and divine wisdom (Binah).

Water:

– Signifies purification, Baptism, and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

– Corresponds to the water of Miriam’s Cup and the manifestation of divine blessings in the physical world (Malkuth).

This duality highlights the completeness of spiritual redemption, encompassing the hidden mystical understanding and the tangible, life-giving sustenance.

Integrating the Symbolism into the Fresco’s Interpretation

By incorporating the Five Cups of the Seder and Kabbalistic symbolism, we deepen our understanding of the fresco at Sant Climent de Taüll:

Mary as the Grail Maiden:

– Her vessel represents not a legendary relic but a profound Eucharistic symbol, capturing the essence of sacramental theology.

– She stands as a bridge between the Old and New Covenants, embodying the fulfilment of divine promises and the hope for ultimate redemption.

The Divine Feminine and the Messianic Hope:

– The parallels between Mary and Miriam highlight the essential role of women in the narrative of salvation.

– The connection to Elijah’s Cup underscores the anticipation of the Messiah and the future revelation of divine mysteries.

Kabbalistic Integration:

– Viewing the vessel through the lens of Binah and Malkuth enriches the theological depth of the artwork.

– It illustrates the flow of divine energy from understanding to action, from the spiritual to the physical, embodied in Mary’s role.

A Multifaceted Symbol of Redemption and Divine Wisdom

The fusion of Passover traditions, Kabbalistic teachings, and Christian iconography in the depiction of Mary with the vessel offers a layered understanding of the fresco’s spiritual significance. It transcends simplistic interpretations tied to Grail legends and invites a contemplation of the universal themes of liberation, divine wisdom, and the unification of humanity with the Divine.

By embracing these interconnected traditions, we recognize Mary as a symbol of the Divine Feminine, the Grail Maiden, and the embodiment of both Binah and Malkuth. This perspective enriches our appreciation of Romanesque art and its capacity to convey complex theological concepts through powerful visual symbolism.

Ultimately, the fresco serves as a timeless meditation on the mysteries of faith, the hope for redemption, and the profound journey from understanding to manifestation—a journey that continues to inspire and resonate across cultures and ages.

If you want to know more about Mary the Magnificat, click on our dedicated article, “The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife”.