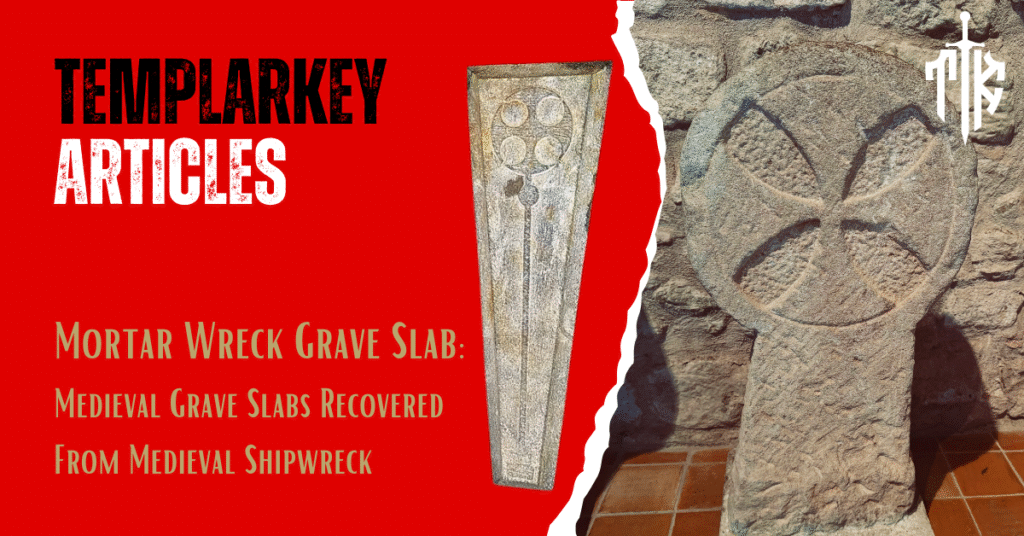

Mortar Wreck Grave Slab: Medieval Grave Slabs Recovered From Medieval Shipwreck

“Was the Studland Bay Mortar Wreck Grave Slab a Templar cross? The Mortar Wreck reveals that one of the tombstones is of Purbeck marble and bears a Discoid Cross. This ship would have sailed medieval trade routes with its precious cargo”.

For most of its life, this grave slab was just a rumour in the dark. It lay face down in the silt on the bottom of Studland Bay for nearly 800 years, in a shipwreck off the coast of Dorset, England, part of what is now known as the Mortar Wreck, its carved cross pressed into the seabed.

On Admiralty charts, the site appeared as a single word – “obstruction” – a bland warning to sailors that concealed the true nature of the wreck below, and which divers soon learned to ignore.

Only when winter storms stripped away sand and sonar lit up the anomaly did the supposed rubble resolve into what it was: the shattered cargo of a 13th-century merchant ship, now known as the Mortar Wreck. In that moment, the sea returned not only a vessel, but an entire lost chapter of England’s stone-built Middle Ages.

The story that slab now tells, standing upright in a new shipwreck gallery at Poole Museum, touches both the casual visitor and the footnote in a specialist journal. It speaks at once of grief, trade, shipbuilding, quarrying, liturgy and power.

The Mortar Wreck: Archaeology of a Shipwreck Lost to Time

The Mortar Wreck is no longer an anonymous obstruction. It is now understood to be a small cargo ship, built in clinker – the overlapping-plank construction typical of northern Europe – that sank in Studland Bay in the mid-13th century, during the reign of Henry III, when cathedrals and great churches were being rebuilt on an unprecedented scale.

“The wreck went down in the height of the Purbeck stone industry, and the grave slabs we have here were a very popular monument for bishops and archbishops across all the cathedrals and monasteries in England at the time,” explained Tom Cousins, a Maritime Archaeologist from Bournemouth University who led the recovery.

Tree-ring analysis of the surviving oak timbers dates their felling to roughly 1242–1265 and points to an Irish source. Combined with the hull form and associated finds, archaeologists can place the vessel in the dense coastal traffic that ringed medieval Britain: small to medium-sized traders moving heavy bulk goods along sea routes far cheaper and more reliable than the rutted roads inland.

The wreck’s nickname comes from its cargo. Around the preserved timbers lies a mound of Purbeck stone grinding mortars, bowls and blocks – some thirty tonnes’ worth – along with copper-alloy cauldrons and braziers that once served the crew’s makeshift galley. This is textbook evidence of a specialised stone carrier: a working ship feeding the voracious appetite of Europe’s masons and patrons for dressed stone.

Medieval Purbeck Marble Grave Slabs Recovered: the Economy of Remembrance

At the heart of the find, however, lies a more particular kind of stone. Mixed with the rough building blocks are long, tapered slabs of Purbeck “marble”: a fossil-rich limestone from the Isle of Purbeck which, when polished, takes on a deep, almost glassy lustre.

Purbeck marble was quarried in both the Romano-British and medieval periods (from the late 12th century onwards). It was used for columns and tombs, architectural mouldings and veneers, mortars and pestles, and a range of other objects. It appears in almost all the great cathedrals of southern England, as well as in Exeter, Ely, Norwich, Chichester, Salisbury, Lincoln, Llandaff, Southwark and Canterbury cathedrals, and is even found in Westminster Abbey. Medieval trade routes for the overseas use of precious Purbeck marble included Normandy, Genoa in the Mediterranean, and the Baltic.

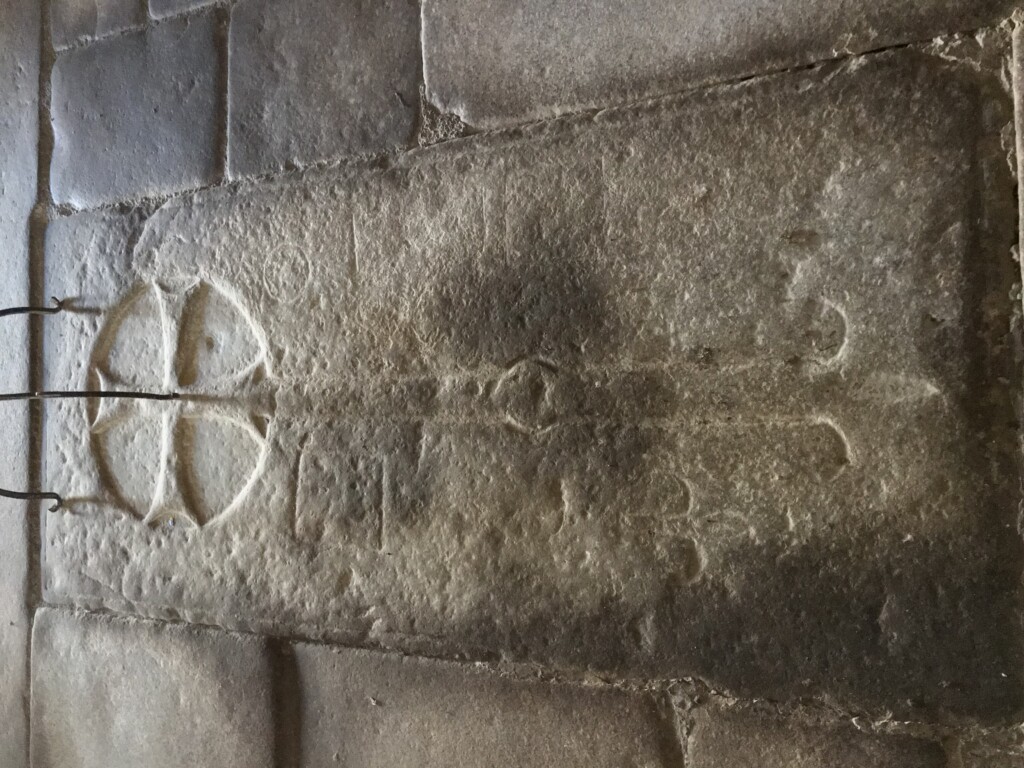

The Mortar Wreck has yielded at least three carved but unpolished Purbeck marble grave slabs, of which two have now been raised. Their iconography – strong central crosses, wheel-heads, and splayed arms – is consistent with the first half of the 13th century.

In both dimensions and design, one slab in particular closely echoes the tomb lid of Archbishop Stephen Langton at Canterbury, a key figure in the politics surrounding Magna Carta. The resemblance does not prove a direct connection, but it firmly anchors the Studland pieces in the same artistic and devotional milieu.

These are not generic paving stones. They are tools of commemoration for the upper reaches of medieval society: bishops, abbots, high-status clergy or nobility whose memory was meant to be fixed in stone and located at the heart of liturgical space.

The fact that they were shipped already carved but not yet fully polished suggests an articulated production chain: quarrying and primary carving near the source, with final finishing and, perhaps, heraldic detailing to follow at the destination.

Crucially, the Mortar Wreck provides the first secure example of such Purbeck grave slabs found as cargo on a historic shipwreck. For historians of medieval art and economy, that single point matters. It moves grave slabs from the static category of “things found in churches” into the dynamic context of long-distance trade, contractual supply and maritime risk.

Purbeck Marble, Discoid Crosses and the Knights Templar Myth

What fixes the eye on the Mortar Wreck Grave Slab is not merely that there is a cross, but what kind of cross it is. The head does not end in straight arms. Instead, the arms are contained within a disc, the circle cutting into the corners of the stone before the shaft runs down through the tapering body of the slab. In formal terms, this is known as a discoid cross, cut on a recumbent tomb slab.

Archaeologists, experts, and historians of medieval funerary art and crypt monuments recognise this as part of the discoid type cross, in the form of a gravemarker. In the British Isles, George Thomson’s survey of disc-headed gravemarkers has shown that such forms, though rare, are distinctive: small head-and-shaft memorials, sometimes called discoid gravemarkers or wheel crosses, recorded in a limited number of Scottish and English churchyards and treated as a coherent type rather than as curiosities.

Later work on two discoid markers from Anglesey has reinforced that conclusion, underlining both the rarity of the form in Britain and its clear Christian function as a grave marker rather than a wayside cross or boundary stone.

On the Continent, particularly in France, the type is better represented and more thoroughly documented. Pierre Ucla’s work on the stèles discoïdales of Languedoc, together with regional studies in Lozère, Hérault, and Aude, has identified substantial groups of Discoid Crosses in parish cemeteries, all firmly linked to Christian funerary use from the Middle Ages onwards. Abbé Joseph Giry and Robert Aussibal’s detailed study of the discoid stelae at Usclas-du-Bosc, for example, demonstrated how a single cemetery in the Hérault could yield a dense concentration of such stones, most bearing some form of cross, and how their symbolism and dating must be approached cautiously and contextually rather than through romantic labels.

The Studland slab sits squarely within this wider, entirely stone-based tradition. Its Discoid Cross shares the same basic grammar: a circular head containing a specific type of cross, above a narrowed body intended to mark an individual grave. The difference lies in scale and finish. The mid-13th-century mortar wreck site included two unpolished grave slabs; one slab measures 1.5 metres in length, while the other, a much larger slab (in two pieces), has a combined length of 2 metres.

Many different British examples are relatively small, whereas French examples include large recumbent tomb covers that are very close in scale to the Studland grave slabs from the mortar wreck. The Mortar Wreck discoid cross slab is a carefully dressed piece intended to lie flat over a high-status burial, but the underlying form is the same. A medieval mason familiar with French church tombs would have recognised it at once.

The presence of such grave stones in regions once held by the military orders has naturally encouraged attempts to read the Discoid Cross as specifically “Templar”. Some cemeteries in Languedoc and neighbouring regions do lie close to former commanderies of the Templars (Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon) and, later, of the Hospitallers (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem), and specialist studies of these landscapes take that overlap seriously. Where inscriptions, documents, or secure archaeological contexts exist, discoid crosses are found marking the graves of local lay families, minor clergy, and parishioners, as well as any possible members or patrons of the orders.

“The form of a Discoid Cross itself is not diagnostic of the Knights Templar. It is a regional Christian funerary type that a wide range of communities could use”.

For the Mortar Wreck grave slab, that restraint matters. On present evidence, the most that can be said securely is that it is a well-made stone grave cover bearing a Discoid Cross of a kind widely attested in France and, more sparingly, in the United Kingdom.

It belongs to the same family as the stone discoid cross tomb slabs recorded in French and British churchyards, and it shows that this repertoire of forms extended into the export trade in carved stone.

Whether the eventual buyer would have been a cathedral chapter, a monastic house, a knightly family, or even a community connected with one of the military orders remains open. The slab itself does not decide that question.

What it does show, with unusual clarity, is how a very specific Christian sign – the discoid cross – could travel. The Studland tombstone captures that sign in motion, caught between quarry, workshop and grave, and now, unexpectedly, between seabed and museum gallery.

Templarkey will publish a historically in-depth study of Christian Crosses in the near future, including discoid crosses and the various “Templar” crosses, illustrated with colour photography of such crosses. See image of a French Grave Slab Discoid Cross.

From Obstruction to Medieval Shipwreck Case Study

“What makes the Mortar Wreck unusually valuable is the way different strands of evidence converge”.

Dendrochronology dates the vessel and hints at the networks through which Irish timber entered English shipyards. The stone cargo documents the reach of Purbeck quarries and the degree to which their products were standardised for export.

The mortars, cauldrons, and associated domestic items show the practical reality of life on board. The grave slabs, finally, connect this working world to the solemn politics of the dead: the ordering of space in cathedrals and priories, the hierarchy of burial and the visibility of tombstones in the liturgical landscape.

Taken together, the site offers what archaeologists strive for but rarely obtain: a context in which trade, technology and theology intersect in a single, datable event. This is not a random scattering of chance finds, but a coherent, stratified assemblage pinned to a particular decade in the 13th century by independent lines of evidence.

From a methodological standpoint, the investigation of the Mortar Wreck has also become a model. The survey has progressed in stages from diver observations to detailed photogrammetry, targeted excavation, and selective recovery. Conservation has been built into the project from the outset, with desalination and slab stabilisation preceding their transfer to museum display. The site has been brought under formal legal protection, and the finds have been placed in a public institution with the capacity to curate and interpret them over the long term.

Poole Museum and the Ethics of Return of the grave slab

The decision to place one of the grave slabs on show at Poole Museum is not simply a matter of visitor appeal, though the stone inevitably draws the eye. It also raises questions about the afterlives of objects that never fulfilled their original purpose.

The slab was carved for a named individual whose identity has been lost. It was intended to mark a grave in a specific sacred space that the ship never reached. To display it now as an archaeological object risks severing it from its intended role as a focus of prayer and commemoration.

Yet the alternative – leaving it in the sea, face down and slowly eroding – would destroy both the object and the information it carries. In bringing the slab ashore, stabilising it, and situating it within a narrative that explains its dual identity as both a liturgical monument and shipwreck cargo, the museum arguably restores a different kind of dignity: the dignity of context, intelligibility, and shared heritage.

Visitors standing before the gravestone at Poole are invited to see more than a rescued curiosity. They are confronted with the fact that the medieval world was deeply connected by water; that local materials like Purbeck marble could acquire continental significance; and that the economy of salvation was literally underpinned by the economy of shipping.

In that sense, the grave slab has finally reached its congregation – not the single church, chapter, cloister or chantry for which it was cut, but a wider public capable of reading in its chiselled cross the long reach of faith, commerce and risk.

What began as an obstruction on a chart has, through patient work and transparent scholarship, become a touchstone for understanding how the stones beneath our feet once travelled, and how the dead of the Middle Ages still shape the landscapes in which we live.

Frequently Asked Questions: Click a question to read about the Mortar Wreck grave slabs

What is the Mortar Wreck off Studland Bay?

The Mortar Wreck is a mid-13th-century merchant shipwreck discovered off Studland Bay, England. It carried a cargo of Purbeck stone, including mortar bowls, building blocks and carved medieval grave slabs.

What cargo was the Mortar Wreck transporting?

The ship was loaded with Purbeck stone objects: mortars and pestles, rough building blocks and Purbeck marble grave slabs. This cargo shows how medieval quarries, workshops and churches were linked by coastal shipping routes.

Why is the Purbeck marble grave slab important?

The Purbeck marble grave slab from the Mortar Wreck is the first securely documented example of a carved medieval tomb slab found as shipborne cargo. It proves that high-status memorials were quarried, carved and exported by sea.

What is a Discoid Cross grave slab?

A Discoid Cross grave slab is a stone tomb cover with a circular head containing a cross above a tapered shaft. It belongs to a wider medieval tradition of discoid grave markers used in Christian cemeteries in France and parts of the British Isles.

Is the Mortar Wreck grave slab a Knights Templar cross?

The Mortar Wreck grave slab bears a Discoid Cross, a Christian funerary design used by different communities in the Middle Ages. The form is not specific to the Knights Templar, and cannot, on its own, identify a Templar burial.

How was Purbeck marble used in medieval England?

Purbeck marble was quarried on the Isle of Purbeck and used for tomb slabs, architectural mouldings, columns, pavements and liturgical furnishings. It appears in major churches and cathedrals such as Canterbury, Salisbury and Westminster Abbey.

Where can I see the Mortar Wreck grave slab today?

One of the Purbeck marble grave slabs recovered from the Mortar Wreck is conserved and displayed at Poole Museum, where visitors can see it in the context of the 13th-century shipwreck and medieval stone trade.

What does the Mortar Wreck reveal about medieval stone trade?

The Mortar Wreck shows that carved Purbeck marble grave slabs and stone mortars were moved in bulk by sea. The site provides a datable snapshot of how medieval stone was quarried, shaped, shipped and installed in high-status churches.

Further Reading:

Bournemouth University, ‘Medieval grave slabs recovered from historic shipwreck’, Bournemouth University News, 7 June 2024.

Bournemouth University, ‘Earliest English medieval shipwreck story on display at Poole Museum’, Bournemouth University News, 27 November 2025.

BBC News, ‘Medieval grave slab from seabed goes on public display’, BBC News 2025.

Cousins, T. ‘The Mortar Wreck: a mid-thirteenth-century ship, wrecked off Studland Bay, Dorset, carrying a cargo of Purbeck stone’, Antiquity, vol. 98, no. 400, pp. 991–1005.

Cousins, T. ‘The discovery and investigation of a thirteenth-century shipwreck’, Antiquity blog, 15 August 2024.

Historic England 2020, ‘Mortar Wreck site, Poole, Dorset: tree-ring analysis of oak timbers’, Research Report 252-2020, Historic England, Swindon.

Historic England 2022, ‘Mortar Wreck, Studland Bay, Dorset, National Heritage List for England’, Scheduled Monument entry.

Radley, D. ‘Medieval grave slabs recovered from 13th-century shipwreck’, Archaeology Magazine, 13 June 2024.

Smithsonian Magazine, ‘England’s oldest surviving shipwreck is a 13th-century merchant vessel’, Smithsonian Magazine, 26 July 2022.