Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother? Dual Messiahs

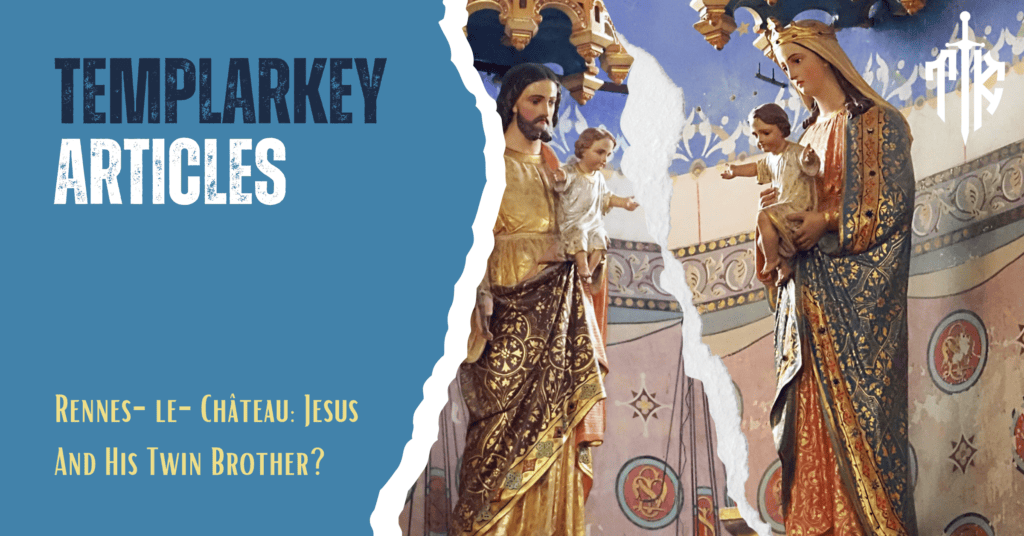

Did Jesus have a twin brother? Are there dual Messiahs? Do the two statues of Jesus, one with Joseph and one with Mary, at the church of Rennes-le-Château prove that Jesus had a twin brother or indicate two separate Messianic figures? To address these provocative theories, it is essential to analyse similar iconographic traditions and longstanding theological interpretations.

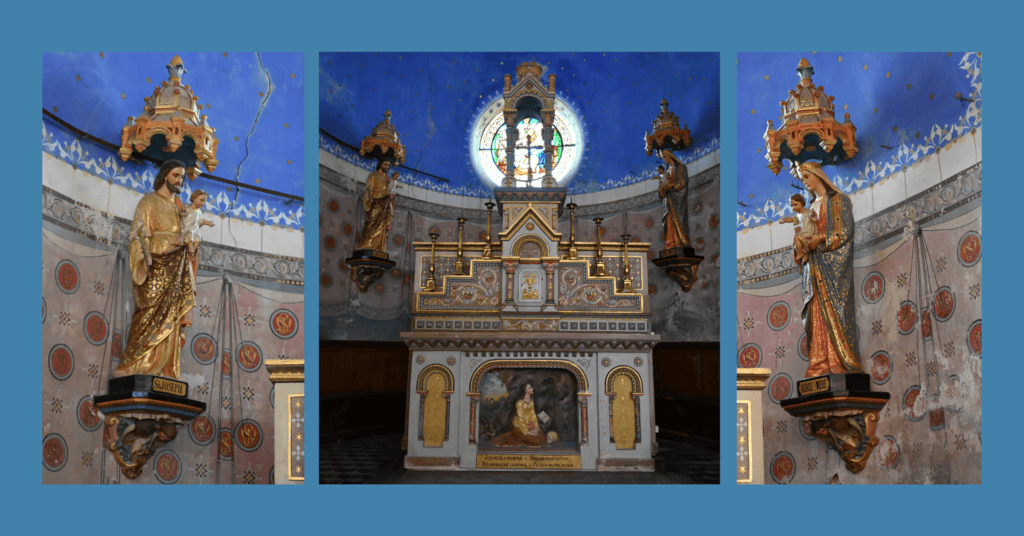

Hidden among the tranquil foothills of southern France, the enigmatic church at Rennes-le-Château continues to intrigue visitors with two powerful depictions of the child Jesus. In one prominent statue, Jesus is held humbly by Mary, who is crowned gloriously as the Queen of Heaven. One Christ, Two Images: Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother? Unveiling the True Meaning Behind the Iconography of The Child Jesus with Mary and Joseph at Rennes-le-Château.

Does the Church at Rennes-le-Château depict Jesus and a secret twin brother? Discover the truth about the two statues of Jesus—one with Mary and another with Joseph, where Jesus rests gently in the arms of Joseph. In each depiction, Jesus remains uncrowned, sparking decades of speculative theories ranging from secret lineages to claims of a mysterious twin brother. However, upon closer theological and historical examination, these statues convey profound religious symbolism rather than concealed family secrets. Raymond E. Brown, one of the leading biblical scholars on infancy narratives, provides context to these theological depictions:

“The infancy scenes are never simple narratives; they are deeply symbolic and theological compositions, presenting different dimensions of Christ’s nature—both fully divine and fully human” (Brown, 1999, p. 37).

Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother: Theology Over Conspiracy

Contrary to sensationalised claims, Rennes-le-Château’s church artwork does not portray two separate figures or suggest secret siblings. Instead, the artistic tradition here follows a well-documented theological symbolism common across Catholic devotional practices. The intentional representation of Christ uncrowned with a crowned Mary symbolically reflects the humility inherent in Christ’s divine incarnation, set against the majestic queenship of his mother. Jaroslav Pelikan explains the theological significance of such depictions in Marian art:

“Mary’s crowned image symbolises her heavenly exaltation, a doctrine clearly established within Catholic tradition, juxtaposed intentionally with Christ’s humble humanity” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 125).

Likewise, the statue of Jesus uncrowned in the arms of Joseph expresses a more intimate, earthly dimension of the incarnation—highlighting the genuine humanity and vulnerability Christ experienced within a family context.

Peter Burke further elaborates on such representations as visual theology rather than historical depiction:

“Religious images were primarily educational tools designed to instruct the faithful in theological truths and devotional practices. Their purpose was symbolic, never literal” (Burke, 2001, p. 44).

Preparing for Comparative Study: Child Jesus Statues Across France

In later sections, this article will explore how similar iconography to – Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother – appears across France, demonstrating that Rennes-le-Château’s statues are exemplary rather than exceptional. Churches throughout the country exhibit comparable statues, often catalogued under the Saint-Sulpician style as used within the modern furnishings within the Church of Rennes-le-Château. Furthermore, unlike the Child Jesus shown at Rennes-le-Château in the arms of the Crowned Mary, other Churches also show a version where Jesus is shown crowned alongside Mary—particularly highlighting her queenship—and consistently uncrowned with Joseph to reflect familial humility.

Such visual themes, produced extensively by workshops like that of Henri Giscard in Toulouse, are not anomalies. Instead, they exemplify widespread devotional norms of the 19th-century French Church, consistently reinforcing theological teachings on the incarnation, humility, and sanctity of the Holy Family.

Decoding Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother: Theology over Conspiracy

Contrary to sensational speculation, the church at Rennes-le-Château does not depict two separate individuals or suggest a hidden twin or secret sibling of Jesus. Instead, the dual imagery communicates a profound theological principle central to Christian doctrine: the harmonious coexistence of Christ’s divine majesty and human vulnerability.

Mary Crowned, Jesus Uncrowned

The depiction of Jesus uncrowned beside Mary, who is crowned as Queen of Heaven, vividly encapsulates the paradox at the heart of the Christian mystery—the divine humility of God incarnate. According to renowned theologian Raymond E. Brown, such imagery encapsulates a theological truth rather than historical fact:

“The infancy narratives express profound theological symbolism rather than literal historical detail, carefully highlighting both the majesty and humility inherent in the incarnation of Christ” (Brown, 1999, p. 52).

By placing a crowned Mary next to an uncrowned child Jesus, the artists responsible for the statues at the church and the mystery of Rennes-le-Château Jesus and His Twin Brother affirm Mary’s exalted spiritual role, recognised by the Catholic Church as the ‘Theotokos’ (God-bearer), while simultaneously accentuating Christ’s divine humility, the hallmark of His earthly presence. This depiction echoes traditional Catholic teachings articulated in documents such as the Second Vatican Council’s Lumen Gentium, which honours Mary as:

“exalted above all angels and men to a place second only to her Son” (Lumen Gentium, 1964, §66).

This purposeful juxtaposition invites viewers not into secret conspiracies, but rather into contemplation of a profound theological truth about Jesus’ incarnation and humility, as clearly defined by Church tradition.

Joseph with Jesus Uncrowned

In the second image, where Joseph cradles the uncrowned child Jesus, the emphasis shifts subtly yet significantly towards Christ’s humanity and familial dependence. Joseph is depicted as a protective, nurturing figure—an intentional portrayal underlining Christ’s full experience of authentic human relationships and domestic life. Jaroslav Pelikan, an eminent historian of Christian thought, clarifies the theological significance of these images of Joseph and Jesus:

“Representations of Saint Joseph in art emerged prominently to emphasise the sanctity of family life and the real humanity of Christ, who entered fully into the ordinary circumstances of human relationships” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 149).

In presenting Jesus uncrowned within the embrace of Joseph, the Saint-Sulpician style statues in the Church at Rennes-le-Château encapsulate a traditional theological narrative: Christ is not merely a distant divinity but an incarnate God experiencing human vulnerability. This teaching finds firm grounding in the Gospel narratives, particularly emphasised by theologian Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, who notes:

“The New Testament narratives purposefully underscore Jesus’ authentic human relationships to stress the reality of the incarnation” (Murphy-O’Connor, 1996, p. 82).

Therefore, the statues depict complementary, not contradictory truths: Christ’s divine humility with Mary and His genuine humanity with Joseph, both essential theological teachings rather than historical curiosities.

The Myth of Jesus’ Twin or Brother

The persistent myth of Jesus having a twin brother finds its origins largely in misunderstood apocryphal writings, notably the Gospel of Thomas. In this text, the apostle Thomas is called “Didymus,” translating to “twin,” a term which some have erroneously interpreted as evidence of Jesus’ literal twin brother. Additionally, ambiguous biblical references to the “brothers of Jesus” (Mark 6:3; Matthew 13:55) have fuelled speculative theories.

However, mainstream scholarship and traditional Church teachings robustly counter these claims. Scholar Elaine Pagels explains that the term “Didymus”, when applied to Thomas, bears a spiritual rather than biological significance:

“Thomas being called “Didymus” or “twin”, symbolically expresses the spiritual kinship or likeness of Thomas to Christ, rather than any biological relationship” (Pagels, 2004, p. 31).

Further addressing the mention of Jesus’ “brothers”, Church historians affirm the longstanding tradition of interpreting these figures as either cousins or stepbrothers—children of Joseph from an earlier marriage—thus preserving the theological doctrine of Mary’s perpetual virginity, as highlighted by Pelikan:

“Early Christian traditions consistently maintained that these “brothers” were either cousins or Joseph’s children from a previous marriage, reaffirming Mary’s perpetual virginity, a belief integral to Catholic and Orthodox doctrines” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 76).

Annette Yoshiko Reed similarly notes:

“The concept of Jesus having biological brothers was not supported by early mainstream Christian communities but emerged primarily in later heterodox interpretations” (Reed, 2015, p. 236).

These scholarly insights clarify that Rennes-le-Château’s art does not indicate a hidden lineage or secret twin. Instead, the church remains aligned with traditional theological symbolism, portraying one Christ figure in two distinct devotional contexts, affirming core Christian beliefs rather than esoteric speculations.

Historical and Theological Evolution of Depicting the Holy Family

| Period | Image with Mary | Image with Joseph | Theological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Christianity | Rare | Absent | Christ as Divine Logos |

| Middle Ages | Mary crowned, Jesus uncrowned | Joseph included in Nativity | Royal maternity, familial piety |

| Renaissance–Baroque | Jesus uncrowned in familial scenes | Joseph increasingly prominent | Theology of Incarnation |

| 19th Century | Mary crowned, Jesus uncrowned | Joseph in domestic devotion | Saint-Sulpician family devotionalism |

The Holy Family Cult in 19th-Century France

The Rennes-le-Château images reflect a broader 19th-century devotional revival in France, which championed the Holy Family as a quintessential model for Christian life. This movement emerged from a desire to reassert traditional Catholic values during a time of significant social and political transformation, echoing a longing for stability, family coherence, and religious renewal.

Mary’s depiction as a crowned Queen of Heaven was central to this revival, reinforcing her status as both divine intercessor and perfect maternal exemplar. According to Sandra Zimdars-Swartz, the elevation of Mary’s image during this era was “deeply connected to a perceived spiritual need for maternal intercession and heavenly patronage amid societal upheaval” (Zimdars-Swartz, 1991, p. 57).

Joseph, traditionally a background figure, gained prominence as a humble protector, representing fidelity, paternal responsibility, and humility. Jaroslav Pelikan notes that this increased devotion to Joseph was part of a deliberate theological strategy to reinforce familial sanctity and Christian masculinity, illustrating Joseph as “the guardian par excellence of the domestic Church” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 165).

The child Jesus, always uncrowned in these portrayals, symbolised humble obedience and divine vulnerability—attributes integral to the Incarnation theology central to Catholic devotional life. Raymond E. Brown highlights this devotional perspective: “The figure of Jesus as an obedient child emphasised His complete identification with humanity, an incarnational theology reinforced by visual and devotional practices” (Brown, 1999, p. 210).

Saint-Sulpician Artistry and the Henri Giscard Workshop

The statues at Rennes-le-Château exemplify the Saint-Sulpician style, a form of religious art dominant in 19th-century France, characterised by its idealised, sentimental, and educational aesthetic. Originating from the influential seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, this artistic style emphasised clear doctrinal teachings through visual simplicity.

Henri Giscard’s renowned workshop in Toulouse was instrumental in producing and disseminating such statues throughout France. These artworks were deliberately accessible and were designed to instruct rather than mystify. According to historian Peter Burke, the clarity of Saint-Sulpician art was intentional: “The explicit visual language was carefully crafted to catechise the faithful clearly, providing theological instruction devoid of ambiguity or secrecy” (Burke, 2001, p. 89). Giscard’s workshop consistently reinforced three central theological themes through these sculptures:

- Incarnation: Emphasising Christ’s true humanity and divine humility.

- Queenship of Mary: Affirming Mary’s heavenly role and intercessory power.

- Sanctity of Family Life: Reinforcing Christian familial virtues through accessible visual narratives.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks: Clarifying the Two Infants

Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated paintings, both titled Virgin of the Rocks (housed in the Louvre and London’s National Gallery), have been frequently misrepresented by conspiracy theorists to support the hypothesis of two Messiahs or secret siblings. In each painting, two infants are depicted alongside Mary, often identified as the infant Jesus and John the Baptist. However, sensationalised interpretations have incorrectly claimed these infants symbolise dual messianic figures or Jesus and an unknown twin brother.

Neither Leonardo da Vinci’s two versions of Virgin of the Rocks nor any authentic strand of early Christian theology supports the notion of literally “two Jesuses.” The two celebrated paintings both depict the Virgin Mary alongside two infants—Jesus and John the Baptist—and an attending angel. Despite speculative theories, these paintings are variations of a common theological scene rather than evidence of multiple historical figures named Jesus.

1. Why Are There Two Versions of Virgin of the Rocks?

Commission and Legal Dispute

Leonardo initially created the altarpiece for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception in Milan around 1483. However, disagreements over payment led him to sell the original privately—this first version now resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris. To resolve legal obligations, Leonardo (possibly assisted by his workshop) later completed a second version, which is displayed in London’s National Gallery.

Artistic Adjustments and Symbolism

Though the two paintings differ in minor details such as composition, colour tone, and the gestures of the angel, their essential theological meaning remains identical. Each portrays Mary, the Christ child, John the Baptist, and an angel in a symbolic grotto setting. As art historian Martin Kemp emphasises, creating multiple interpretations of a single subject was common practice during the Renaissance, driven by patronage requirements rather than hidden theological assertions (Kemp, Leonardo, 2004, p. 142). Thus, variations between the two artworks are typical artistic adaptations rather than subtle indicators of dual Messianic identities.

2. Identifying the Two Infants

The two children consistently depicted in these works are clearly identifiable by established Christian iconography:

- Jesus: Usually positioned closely to Mary, representing his divine origin and central theological importance.

- John the Baptist: Typically shown kneeling or praying, symbolically foreshadowing his prophetic role and recognition of Jesus’s divinity.

Although Christian tradition maintains John was approximately six months older than Jesus, Renaissance symbolism frequently depicted them as infants or small children together, highlighting their intertwined spiritual destinies rather than historical accuracy. Leonardo’s paintings illustrate precisely this symbolic approach—emphasising spiritual truths over chronological exactness.

3. Early Christian Theology and the Doctrine of One Christ

One Christ, Two Natures

From Christianity’s earliest theological formulations, culminating at the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451), orthodox doctrine consistently affirmed Jesus Christ as a single person possessing two inseparable natures—fully divine and fully human. Historian Jaroslav Pelikan notes that Chalcedon explicitly rejected any division of Christ into separate beings or persons (Pelikan, The Christian Tradition, Vol. 1, 1971, p. 263).

Absence of a Tradition of Multiple Historical Jesuses

Throughout early church history, certain heresies—such as Nestorianism—were accused of splitting Christ’s unity into two separate entities, but such doctrines were decisively repudiated by mainstream Christianity. There is no credible early Christian tradition proposing two literal historical figures named Jesus.

Jesus and John’s Intertwined Mission

The canonical gospels explicitly portray Jesus and John the Baptist as distinct individuals whose lives and ministries were closely connected: John preparing the way prophetically for Jesus. Renaissance artists, therefore, consistently portrayed both together, reflecting their profound theological link rather than implying the existence of multiple Jesuses.

Artistic Tradition, Not Hidden Theology

Leonardo da Vinci’s two versions of Virgin of the Rocks demonstrate a typical Renaissance practice—producing multiple versions of an artwork due to patronage or practical circumstances—not a covert belief in multiple Messianic figures. All early Christian theology consistently affirms the unity of Jesus Christ as one divine-human figure. Neither historical nor theological evidence supports the existence of two separate Jesuses, nor do Leonardo’s celebrated paintings suggest otherwise.

Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated paintings, both titled Virgin of the Rocks (housed in the Louvre and London’s National Gallery), have been frequently misrepresented by conspiracy theorists to support the hypothesis of two Messiahs or secret siblings. In each painting, two infants are depicted alongside Mary, often identified as the infant Jesus and John the Baptist. However, sensationalised interpretations have incorrectly claimed these infants symbolise dual messianic figures or Jesus and an unknown twin brother.

Art historians universally reject these speculative interpretations. Professor Martin Kemp, the world-renowned Leonardo scholar, decisively states:

“The infants depicted are clearly identifiable through traditional iconography as Christ and John the Baptist. Leonardo’s symbolism was sophisticated, yet always rooted in established religious doctrine, not hidden genealogies or secret twins.” (Kemp, Leonardo, 2004, p. 147).

Moreover, the apocryphal and sensationalised association of these artworks with the dual Messiah hypothesis neglects the clear biblical and theological distinction historically understood between Christ and John the Baptist. John’s role was explicitly prophetic and preparatory, clearly established in canonical gospels (Mark 1:1-11, John 1:19-34).

Historical theologian Jaroslav Pelikan notes that Renaissance depictions of multiple holy infants in a single scene were common devotional practices, designed to illustrate complex theological relationships and not literal family bonds:

“Renaissance artists frequently placed the infant Jesus alongside John the Baptist to visually articulate theological ideas of prophetic fulfilment and Messianic preparation, never to imply secret twinship” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 180).

Thus, The Virgin of the Rocks supports neither the dual Messiah theory nor the twin Jesus narrative promoted by speculative literature.

The Myth of Two Messiahs: Historical Misunderstandings and Scholarly Refutation

The concept of multiple Messiahs is not entirely modern but arises from ancient Jewish literature, notably found in Qumranic texts like the Dead Sea Scrolls. Some ancient Jewish communities indeed awaited multiple distinct Messianic figures:

- A prophetic Messiah (like Moses).

- A royal Messiah (Messiah ben David).

- A priestly Messiah (Messiah ben Aaron).

As expert biblical scholar Joseph Fitzmyer notes, these figures appear separately in texts like the Community Rule from Qumran, reflecting evolving messianic expectations in pre-Christian Judaism (Fitzmyer, The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins, 2000, pp. 73-75).

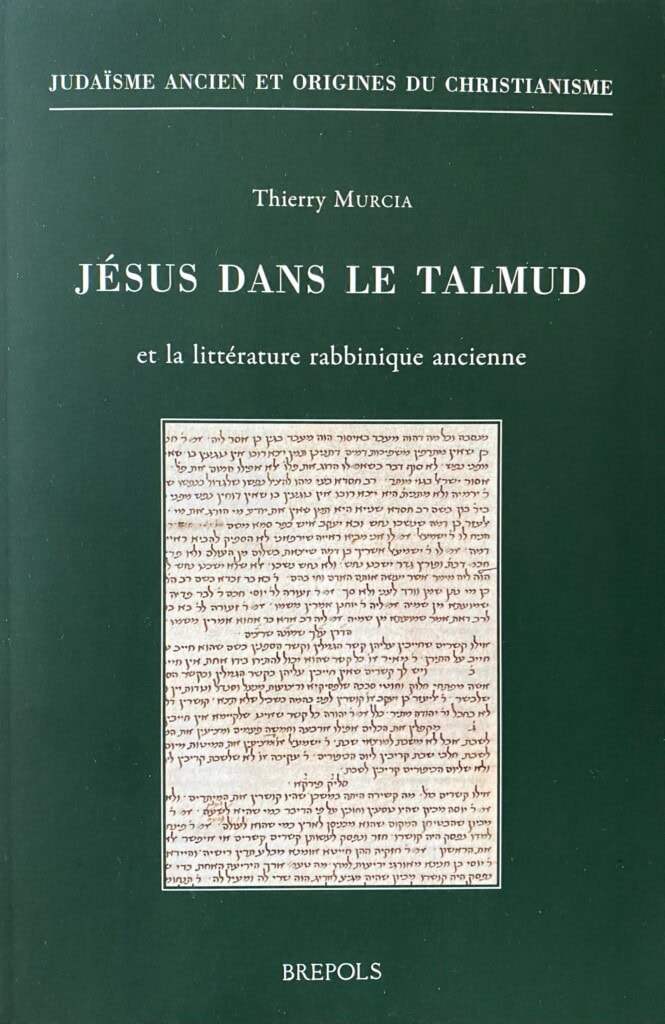

However, contemporary speculative authors mistakenly conflate these distinct figures into two physical brothers or twins. Prominent historian and biblical scholar Thierry Murcia, a leading expert on Jesus in Jewish literature, explicitly critiques such simplistic assumptions. In his comprehensive study Jésus dans le Talmud et la littérature rabbinique ancienne, Thierry Murcia examines the Talmudic references to figures such as “Ben Stada” and “Ben Pantera”.

Murcia concludes that these appellations are not credible historical claims of biological siblings or twins of Jesus. Instead, they are polemical portrayals and symbolic accusations of illegitimacy or heresy, reflecting the complex dynamics between early Judaism and emerging Christianity.

Murcia’s analysis underscores that these Talmudic references should be understood within their historical and literary contexts, rather than as literal accounts of Jesus’s familial relations. This perspective aligns with the scholarly consensus that such texts are more indicative of interreligious polemics than factual biographical information. Thus, the modern sensationalist theory of twin Messiahs is based on profound misunderstandings of ancient texts and deliberate misinterpretations of artistic symbolism.

The True Meaning: Messiah ben Joseph and Messiah ben David

The two genealogies of Jesus found in Matthew (1:1-17) and Luke (3:23-38) intentionally blend the lineage of the two significant messianic traditions—Messiah ben Joseph and Messiah ben David—into one figure: Jesus of Nazareth. The concept of two distinct messianic lineages was indeed present in Jewish theology, describing:

- Messiah ben Joseph: A suffering servant figure, destined to gather nations but ultimately facing persecution and death. Symbolically referred to as the “Leviathan,” this Messiah embodied a universalistic vision (Genesis 49, Isaiah 53).

- Messiah ben David: A royal figure destined to reign triumphantly, restoring Israel and establishing peace (2 Samuel 7, Jeremiah 23).

Scholars recognise this integration explicitly in Jesus’ dual genealogies. Biblical historian Geza Vermes explains clearly:

“The New Testament genealogies are theological compositions designed to assert Jesus’ role as both the suffering, universally accessible Messiah ben Joseph, and the royal Messiah ben David. They are not historical contradictions but deliberate theological assertions of Jesus fulfilling multiple messianic expectations.” (Vermes, Jesus the Jew, 1973, p. 97).

Scholarly Insights: Messiah ben Joseph and Messiah ben David

Scholarly debate on messianism, extensively explored in a 2010 Paris colloquium published by historian David Hamidović, highlights that early Jewish thought expected not one, but multiple messianic figures: royal, priestly, and prophetic. Contrary to popular modern myths, these expectations did not suggest literal twins or biological siblings, but distinct theological roles evolving from ancient Near Eastern traditions into complex Second Temple period expectations.

Historians Thomas Römer and John J. Collins demonstrate that biblical texts evolved from royal ideologies to complex messianic hopes. Römer notes that after the Babylonian exile ended the Davidic monarchy, Jewish thought diversified—some hoped for restoration of a Davidic figure, others embraced foreign rulers like Cyrus as divinely appointed “messiahs.” Collins stresses that “royal Psalms” were only occasionally interpreted messianically, with such interpretations becoming prominent primarily in later Jewish and early Christian traditions.

Additionally, experts such as Simon Mimouni and José Costa reveal that the concept of dual messiahs—one suffering (ben Joseph) and another royal (ben David)—is deeply rooted in ancient Jewish theology. Mimouni explains that early Christians explicitly merged these two messianic expectations within Jesus’ genealogies, emphasising his Davidic lineage and universal priesthood (according to Melchizedek), blending royal and priestly messianic roles.

Finally, Frantz Grenet and Mireille Hadas-Lebel highlight the varied influences shaping messianic thought, noting possible contributions from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Canaanite, and Iranian traditions, although these were significantly adapted and reshaped within Jewish religious contexts.

Thus, contemporary conspiracy theories that simplistically posit dual messiahs as literal twins or secret siblings completely misunderstand these historical, theological traditions. Instead, as these experts affirm, messianic duality symbolically expresses profound theological diversity rather than hidden biological lineages or literal duality.

The Real Theology Behind the Imagery

Ultimately, the Rennes-le-Château statues represent traditional Roman Catholic devotional theology rather than secret twins or dual Messiahs. Historical, theological, and scholarly consensus strongly confirms that these artworks symbolise:

- Christ’s humble incarnation (Messiah ben Joseph symbolism).

- Mary’s heavenly queenship and intercession.

- Joseph’s faithful guardianship and family sanctity.

Claims of hidden twins or dual messianic lineages misinterpret Jewish messianic traditions, overlook ancient theological symbolism, and misrepresent historical and biblical scholarship. Instead, the dual genealogies and dual imagery of Christ reflect profound theological insights, intentionally integrated to present Jesus as the fulfilment of comprehensive messianic expectations.

Visitors to Rennes-le-Château, or viewers of Leonardo’s masterpieces, gain more by contemplating these profound religious truths rather than chasing conspiratorial shadows. The authentic “secret” these artworks share is their invitation to meditate deeply upon Jesus’ divine humility, universal kingship, and human vulnerability, embracing the profound theological mystery rather than the sensationalist myth.

Who Started the Myth of Jesus’ Brother at Rennes-le-Château?

The modern myth alleging Jesus had a twin or hidden sibling depicted at Rennes-le-Château originated largely with 20th-century propagators of Fantastic Realism, speculative authors and conspiracy theorists. Notably, the British authors Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln popularised this idea in their 1982 bestseller, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. This speculative work suggested that Rennes-le-Château contained encoded evidence supporting claims of hidden lineages descending from Jesus himself.

The theory was dramatically amplified by Dan Brown’s popular novel, The Da Vinci Code (2003), which fictionalised this notion further. However, as historian Annette Yoshiko Reed clearly states:

“These ideas are modern constructs with no credible historical or theological basis, derived from misinterpretations and imaginative conjectures about early Christian apocrypha and medieval symbolism” (Reed, 2015, p. 240).

The initial seed of this theory, linking Rennes-le-Château explicitly to a secret sibling or twin of Jesus, traces primarily to sensationalist literature rather than genuine historical research.

The Real Mystery of Rennes-le-Château: A Theological Conclusion

It is also worth emphasising that, both in Jewish messianic traditions and in the early Christian reinterpretation of them, the various expected messiahs—whether priestly, prophetic, or royal—did not share a single bloodline. The Messiah ben David and Messiah ben Joseph traditions, for example, originate from distinct tribal lineages (Judah and Ephraim, respectively), and the priestly Messiah of Aaron derives from yet another (Levi). There is no precedent in ancient sources for requiring visible signs such as a crown to authenticate a messianic identity.

In the church of Rennes-le-Château, both representations of the child Jesus—whether in the arms of Joseph or beside the crowned Virgin Mary—show him without a crown. If Abbé Bérenger Saunière had subscribed to the pseudo-historical theory that a crown signifies a messiah, he could not have viewed either statue as depicting the Messiah. Ironically, by such logic, the very theory collapses under its own symbolic misunderstanding, reinforcing instead the traditional theological truth: that the messianic identity of Jesus lies not in external regalia, but in his union of divinity and humility.

Thus, there are no Messiahs depicted, as neither are crowned nor is there a royal Bloodline in this Church. If Abbé Bérenger Saunière wanted to give a clue to a secret Bloodline under the identity of Joseph, he could have had a statue of Joseph crowned or with Jesus crowned being held by Joseph. None of the researchers or best-selling authors who have written about Rennes-le-Château venture into the Kabbalistic understanding of the Messiahs, Ben Joseph (Leviathan), or Ben David. Nor do they mention the Glorious Body and the Divine Light.

The true mystery of Rennes-le-Château is not one of hidden bloodlines or cryptic twins. Instead, it is the theological depth and clarity embedded within its religious art. Far from secretive, these images powerfully communicate foundational Christian teachings:

- Divine humility and human vulnerability of Christ—expressed vividly through His consistent portrayal as uncrowned, emphasising approachability and incarnational humility.

- Exalted queenship and maternal intercession of Mary—illustrated through her crown and elevated status, reinforcing her role in Catholic devotional practice.

- Earthly fidelity and quiet guardianship of Joseph—depicted as the quintessential protective father figure, modelling Christian virtues of humility, responsibility, and care.

Visitors drawn by speculative narratives should instead appreciate Rennes-le-Château for its authentic and profound spiritual symbolism. The genuine wonder of the village’s small church lies in how effectively it distils complex theological truths into accessible, devotional art. As Jaroslav Pelikan succinctly notes:

“Christian art is most powerful when it invites contemplation rather than confusion, clarity rather than conspiracy” (Pelikan, 1998, p. 202).

Like all Roman Catholic churches, Rennes-le-Château’s modest modern Saint-Sulpician-styled church beautifully embodies this principle, making it a true spiritual treasure, not a keeper of secrets.

Why Templarkey Investigates: Beyond the Illusions of Literary Myth

Despite clear evidence that the theory of “two Jesuses” and other such claims are literary inventions crafted for editorial or sensational purposes, few are willing to confront the fact that these narratives are modern fabrications. Authors and publishers have at times sought to capitalise on the enduring allure of Rennes-le-Château, using it to market books or gain visibility, often targeting international audiences hungry for mystery.

Yet it was the Anglo-American publishing machine that truly transformed these myths into a lucrative global enterprise. What began as speculative fiction inspired by surrealist imagination and esoteric curiosity has, over time, taken on a life of its own—blurring the lines between fantasy and historical reality. In some circles, these modern myths are now perceived as more “real” than verifiable critical scholarship. Admitting one has been misled by fantastical reinterpretations of history is rarely easy, particularly when the fiction was seductive, poetic, and profitable.

This is precisely why Templarkey exists: to stand at the crossroads of literature and historical truth, helping readers navigate between genuine research and modern mythmaking. Our editorial team draws from both literary analysis and rigorous academic methods, and we do so with direct experience from within inner esoteric and initiatory circles—something that many commercial authors lack.

For those abroad, the Rennes-le-Château narrative has often been entangled with various ideological, spiritual, and commercial agendas. We are well aware that entire industries have been built on conflating esoteric fiction with supposed historical facts. If your interest lies in perpetuating illusion, or if you knowingly mislead others for entertainment or gain, Templarkey is not for you. We leave that to your conscience. But if you seek to uncover what is true—however complex, nuanced, or less marketable that truth may be—then we welcome you. We stand for intellectual integrity, historical accuracy, and the responsible exploration of spiritual traditions. That is our commitment, and it is why we continue this work.

Bibliography:

- Baigent, Michael, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln. The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. Jonathan Cape, 1982.

- Brown, Dan. The Da Vinci Code. Doubleday, 2003.

- Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library, 1999.

- Burke, Peter. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. Cornell University Press, 2001.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins. Eerdmans, 2000.

- Kemp, Martin. Leonardo. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Murcia, Thierry. Jésus dans le Talmud et la littérature rabbinique ancienne. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014.

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. Paul: A Critical Life. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Pagels, Elaine. Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. Random House, 2004.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture. Yale University Press, 1998.

- Reed, Annette Yoshiko. “Afterlives of New Testament Apocrypha,” in The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Apocrypha. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Second Vatican Council. Lumen Gentium: Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. 1964.

- The Templarkey Magazine, “Fantastic Realism books from France” Issue 3 (April 2022).

- Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels. Fortress Press, 1973.

- Zimdars-Swartz, Sandra L. Encountering Mary: From La Salette to Medjugorje. Princeton University Press, 1991.