The Kybalion: Hermetic Philosophy of Three Initiates or The Borrowed Ideas of William Walker Atkinson?

The Kybalion: Hermetic Philosophy, originally published in 1908 Published in 1912 by “The Yogi Publication Society Masonic Temple” in Chicago, Illinois, under the pseudonymous “Three Initiates,” has been heralded by some as a foundational text of modern esotericism. However, its authorship and authenticity as a Hermetic work are fraught with controversy.

The Kybalion: Hermetic Philosophy, originally published in 1908 Published in 1912 by “The Yogi Publication Society Masonic Temple” in Chicago, Illinois, under the pseudonymous “Three Initiates,” has been heralded by some as a foundational text of modern esotericism. However, its authorship and authenticity as a Hermetic work are fraught with controversy.

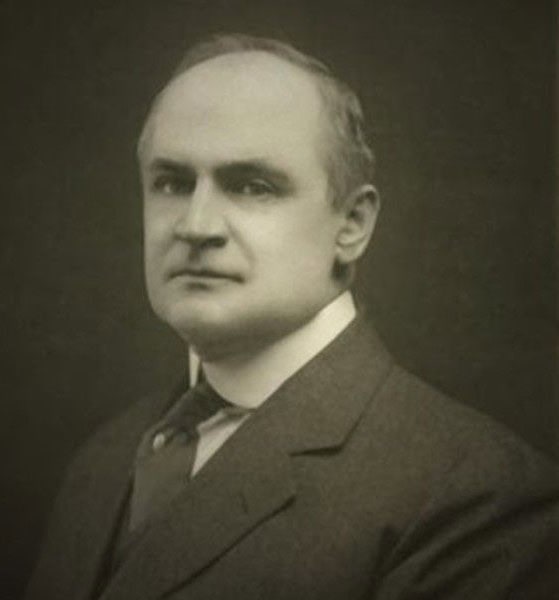

Widely believed to have been written by William Walker Atkinson, a prolific but questionable figure in the “New Thought” and “New Age” movements, the book’s claims to ancient wisdom crumble under scrutiny.

Atkinson not only appropriated ideas from various traditions but also perpetuated his influence in subsequent, lesser-known works like The Seven Cosmic Laws, which further expose his pattern of recycling and rebranding ideas that were not his own. For more on William Walker Atkinson, click his Wikipedia page.

The “Three Initiates Kybalion” and the William Walker Atkinson Connection

The anonymity of the “Three Initiates” was a clever marketing device designed to imbue The Kybalion with an aura of ancient authority. However, the book’s style, language, and themes align unmistakably with the work of William Walker Atkinson. A key figure in the “New Thought” movement, the attorney, merchant, publisher, and author Atkinson had a reputation for producing an extraordinary volume of work under multiple pseudonyms, often giving the illusion of a vast spiritual network that, in reality, consisted only of himself.

Evidence strongly suggests that Atkinson was the sole author of The Kybalion. He later continued exploring the same principles in The Seven Cosmic Laws, a post-Kybalion work that rehashed much of the same material under a new title. This pattern of recycling ideas under different guises was a hallmark of Atkinson’s career.

Atkinson’s Web of Pseudonyms

William Walker Atkinson’s use of pseudonyms was not just prolific—it was strategic. Over the course of his career, he wrote under an astonishing number of aliases, creating the illusion of a diverse array of voices and authorities in esoteric and metaphysical literature. Among his most notable pseudonyms were:

Yogi Ramacharaka: Atkinson used this alias to write about yoga, Hindu philosophy, and Eastern spiritual practices. Despite the authentic-sounding name, his writings were steeped in Western interpretations of Eastern traditions, often oversimplifying or distorting their complexities.

Swami Panchadasi: Under this pseudonym, Atkinson authored works on clairvoyance and occultism, as many faux Hindus did by presenting themselves as masters of mystical practices. We must take care of these fake masters. Recall the character thought to be a Lama: Lobsang Rampa (Cyril Henry Hoskin), author of ‘The Third Eye’.

Theron Q. Dumont: This alias (supposed to be French) focused on mental training and personal magnetism, blending “New Thought” ideas with pseudo-scientific techniques.

Magus Incognito: Another of Atkinson’s personas, this pseudonym was used to explore general occult and esoteric topics, often overlapping with his other writings.

The adoption of these pseudonyms served several purposes:

- Credibility: By presenting himself as multiple “experts,” Atkinson lent his works an air of authority that his name alone might not have commanded.

- Mystique: Pseudonyms like “Yogi Ramacharaka” and “Swami Panchadasi” gave his writings an exotic appeal, capitalising on the early 20th century’s fascination with Eastern mysticism.

- Profit: The sheer volume of his output under various names allowed him to dominate the New Thought and occult book markets, reaching different audiences with tailored messaging.

Critics argue that this approach was deceptive, fostering a false sense of authenticity and expertise. Instead of contributing original insights, Atkinson’s pseudonyms often rehashed existing ideas in slightly altered formats, muddying the waters of genuine esoteric and spiritual studies.

Seven Hermetic Principles or New Thought Appropriation?

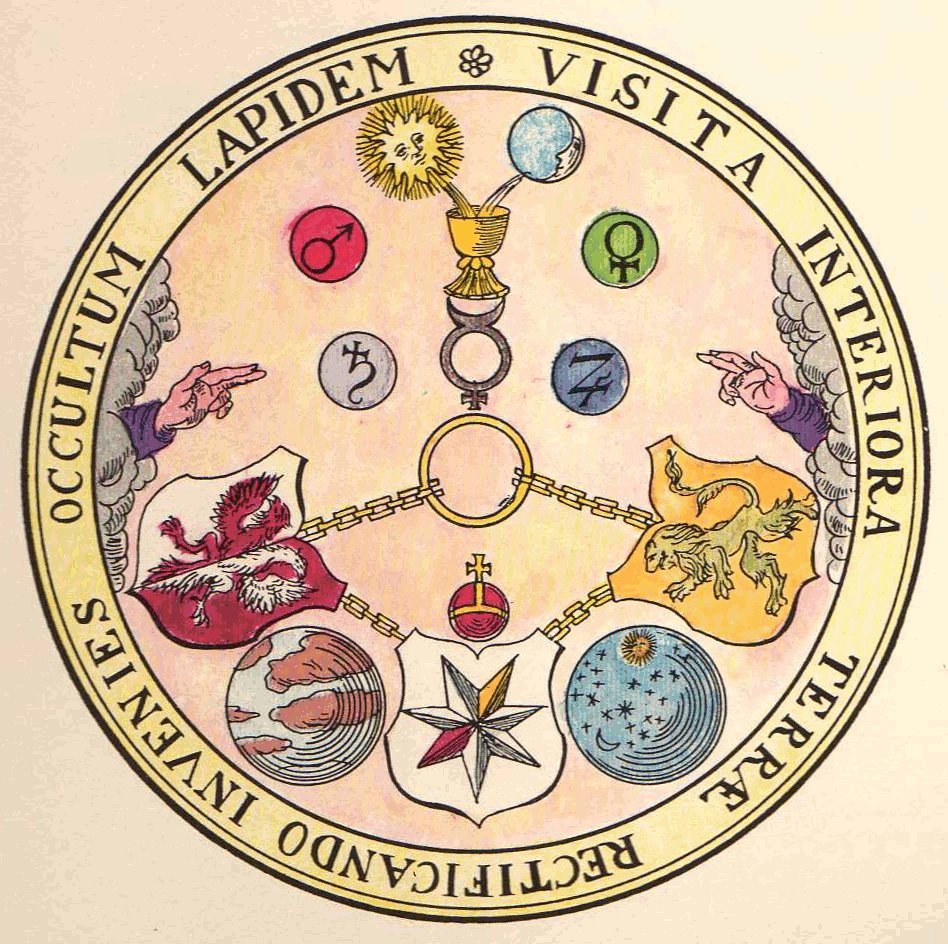

The Kybalion purports to distil the core teachings of Hermeticism, rooted in the ancient wisdom of Hermes Trismegistus. However, its seven principles—Mentalism, Correspondence, Vibration, Polarity, Rhythm, Cause and Effect, and Gender—bear little resemblance to authentic Hermetic texts like the Corpus Hermeticum. Instead, they align more closely with the New Thought movement’s focus on mental power, positive thinking, and personal transformation.

Atkinson’s “cosmic laws” borrow heavily from 19th-century spiritualism, pseudo-scientific theories, and existing esoteric traditions. The principle of Mentalism, for example, echoes New Thought’s central tenet: “thoughts create reality.” Similarly, Polarity and Vibration reflect ideas found in 19th-century mesmerism and occult literature. What Atkinson presented as timeless Hermetic wisdom was, in reality, a synthesis of contemporary spiritual trends.

The Seven Cosmic Laws: Repetition Without Innovation

The Seven Cosmic Laws, a lesser-known follow-up to The Kybalion, reveals Atkinson’s strategy of presenting “New Thought” ideas in esoteric packaging. The work reiterates the same core principles introduced in The Kybalion, rebranding them without significant innovation. This work further exemplifies Atkinson’s pattern of repackaging ideas under different titles and pseudonyms to maintain his relevance and market presence.

Borrowed Ideas, Repackaged Concepts

Atkinson’s work demonstrates little originality. His primary contributions were not new ideas but rather the repackaging of existing ones to suit the tastes of early 20th-century spiritual seekers. Key sources for The Kybalion and The Seven Cosmic Laws include:

- Hermeticism: Simplified and Westernised interpretations of Hermetic teachings, divorced from their original context.

- New Thought Philosophy: Core principles like Mentalism and Cause and Effect stem directly from New Thought, not ancient Hermetic texts.

- Occult and Esoteric Literature: Influences from Theosophy and 19th-century occultists like Helena Blavatsky and Eliphas Levi.

- Eastern Philosophy: Superficial borrowing from Hinduism and Buddhism, distorted to fit Western metaphysical frameworks.

Was Atkinson a Martinist or a Member of a Secret French Order?

Recent inquiries into William Walker Atkinson’s esoteric affiliations have raised questions about his possible involvement with Martinism or other secret societies in France. While Atkinson wrote extensively on mysticism, occultism, and Hermetic philosophy, there is no conclusive evidence that he was formally initiated into the Martinist Order or any similar French organisation. These speculations largely arise from thematic parallels in his work and his use of pseudonyms like Magus Incognito, which evoke the secrecy associated with such groups.

Parallels with Martinist Thought

Atkinson’s writings occasionally overlap with Martinist principles, particularly in their focus on spiritual regeneration, personal enlightenment, and the ascent of the soul. For instance, in his work The Secret Doctrine of the Rosicrucians (under the pseudonym Magus Incognito), he writes:

“The soul must rise above the material world, guided by the inner light, to achieve union with the Universal Spirit.”

This idea echoes the mystical Christian focus of Martinism, which emphasises the soul’s return to the Divine. However, such themes are not unique to Martinism and are found across a broad spectrum of Western esotericism.

French Esotericism in Atkinson’s Work

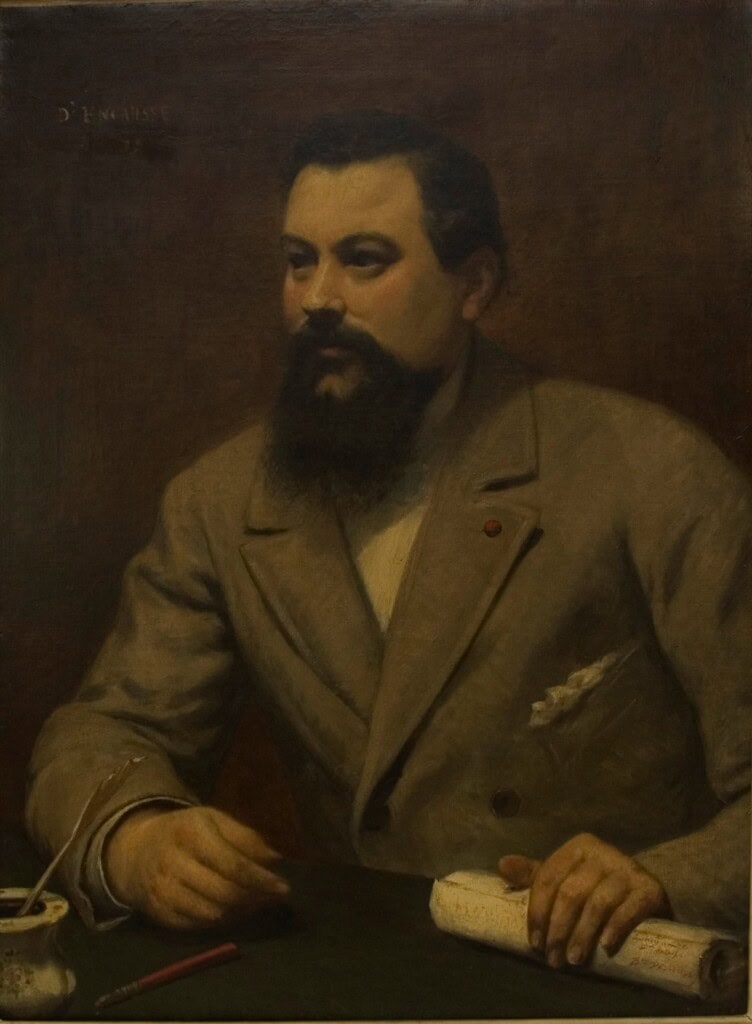

The flourishing of occultism in France during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, led by figures such as Gérard Encausse (Papus), Éliphas Lévi, and Joséphin Péladan, undoubtedly influenced Atkinson’s writings. French esoteric movements like Martinism, the Rosicrucian revival, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn shared a fascination with Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and alchemical symbolism—all themes present in Atkinson’s work. However, his engagement with these ideas appears to be indirect:

- Literary Borrowing: Atkinson likely absorbed French esoteric concepts through translated works and popular occult publications rather than personal involvement. His use of pseudonyms and mystical terminology suggests an awareness of the allure of French occultism but not a direct connection.

- No Verifiable Membership: Unlike prominent Martinists, Atkinson left no evidence of initiation into formal orders. Membership rosters and documented activities of French secret societies from this era do not include his name or pseudonyms.

Speculation About Secret Orders

Some have speculated that Atkinson’s pseudonyms, particularly Magus Incognito, were meant to suggest membership in esoteric orders. Templarkey magazine Issue 9 [October 2023] has an article that will fascinate readers interested in secret orders, “Neo-Rosicrucians and The Polaire Brotherhood”. The very title of his work, The Secret Doctrine of the Rosicrucians, hints at hidden affiliations. However, this appears to have been a literary device rather than a reflection of reality. As Wouter J. Hanegraaff notes in Esotericism and the Academy:

“The esoteric revival of the late 19th century was characterised by a blending of traditions, where many authors sought to construct a connection to mythical lineages and ancient wisdom to lend their works credibility.”

Atkinson fits this mould, positioning himself as an authority on hidden teachings without verifiable ties to established orders.

Influence Without Affiliation

The thematic similarity between Atkinson’s writings and Martinist thought, along with his apparent familiarity with French occult traditions, underscores his ability to synthesise and repurpose esoteric ideas. While his works reference Rosicrucianism, Hermeticism, and mystical Christianity, they lack the depth and specificity that would indicate direct involvement in these traditions. Instead, they reflect a broader trend of early 20th-century spiritual writers appropriating symbols and concepts to appeal to a burgeoning audience of seekers.

Quotes and References:

1. William Walker Atkinson (as Magus Incognito): — The Secret Doctrine of the Rosicrucians, 1918.

“True initiation lies not in ceremonies or secret rites, but in the awakening of the inner self to the divine truths that govern the cosmos.”

2. Wouter J. Hanegraaff: — Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

“Esoteric authors often adopted the language of secrecy and initiation not because of personal affiliations, but to legitimise their works in a cultural climate that valued mystique over verifiability.”

3. Joscelyn Godwin: — The Theosophical Enlightenment, State University of New York Press, 1994.

“Many 20th-century writers like Atkinson created a mosaic of esoteric ideas from public sources, adopting the terminology of secret orders without ever participating in their structures.”

A Self-Styled Mystic

While Atkinson’s writings as Magus Incognito evoke the themes of Martinism and French esotericism, there is no substantiated evidence that he belonged to these traditions or their secret orders. His work reflects a broad synthesis of accessible occult literature rather than insights gained from personal initiation. Atkinson’s enduring influence lies not in authentic membership within esoteric orders but in his ability to weave a compelling narrative that continues to captivate readers.

The Corpus Hermeticum: The True Foundation of The Study of The Hermetic Philosophy

While works like The Kybalion claim to distil ancient Hermetic wisdom, serious students of Hermetic philosophy are better served by studying the Corpus Hermeticum. This collection of writings, attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, forms the cornerstone of authentic Hermetic thought.

While works like The Kybalion claim to distil ancient Hermetic wisdom, serious students of Hermetic philosophy are better served by studying the Corpus Hermeticum. This collection of writings, attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, forms the cornerstone of authentic Hermetic thought.

Its focus on the divine, the cosmos, and the soul’s journey provides a profound exploration of philosophical, theological, and mystical themes. Unlike the modern reinterpretations found in The Kybalion, the Corpus Hermeticum represents a genuine link to ancient traditions, making it indispensable for understanding Hermetic philosophy.

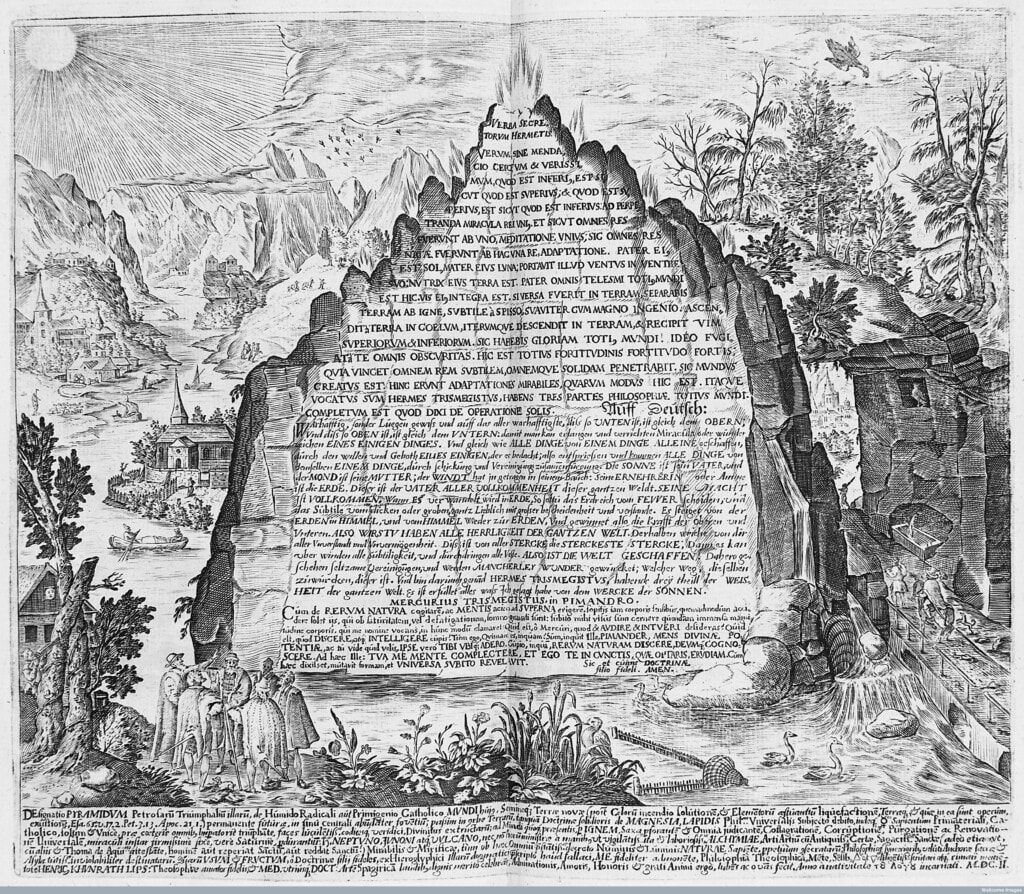

Misunderstanding the Hermetic Texts: The Emerald Tablet and The Kybalion’s Simplifications

One of the most revered Hermetic texts, the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, presents profound teachings on the unity of all things, emphasizing the interconnectedness of the cosmos and the process of transformation. Its famous maxim, “As above, so below,” encapsulates a principle of correspondence that links the macrocosm with the microcosm in a deeply spiritual and philosophical context. However, William Walker Atkinson, in The Kybalion, oversimplifies these ideas, reducing Hermetic principles such as Cause and Effect, Polarity, and Rhythm to a mechanistic framework more aligned with “New Thought’s” mentalism than the spiritual depth of Hermetic philosophy. A good summary of The Kybalion was written by Nicholas E. Chapel, “The Kybalion’s New Clothes: An Early 20th Century Text’s Dubious Association with Hermeticism”, in the Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition No. 24, Vol. 3. Vernall Equinox 2013.

Atkinson’s interpretation of the Emerald Tablet’s teachings about cause and effect, for instance, reframes this principle as a deterministic law of mental influence, sidestepping its broader metaphysical implications about the harmony of divine will and cosmic order. Similarly, his claims about the “pair of opposites” and “everything is dual” misunderstand the nuanced dialectics of Hermetic polarity, which is not about conflict but about the unity of opposites through divine reconciliation.

Atkinson’s reduction of the principle of rhythm to simplistic oscillations between extremes misses the Hermetic insight that rhythm is the manifestation of cosmic balance, governed by a transcendent unity rather than an endless pendulum swing. The same goes for his simplifications of “everything flows”, “cause and effect”, and “everything has poles”. These oversights reflect The Kybalion’s failure to grasp the spiritual subtleties of authentic Hermetic texts, favouring a superficial reinterpretation that prioritizes personal power over universal harmony.

A Historical and Philosophical Treasure

The Corpus Hermeticum consists of a series of dialogues and treatises written in Greek during the early centuries of the Common Era. It was central to the spiritual and intellectual revival of the Renaissance, particularly after being translated into Latin in the 15th century by the renowned Italian humanist and scholar Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499). Commissioned by Cosimo de Medici, Ficino’s translation introduced Hermetic teachings to a new audience, inspiring thinkers across Europe.

Ficino regarded the Corpus Hermeticum as a source of divine wisdom, placing it alongside works by Plato and Aristotle as essential to understanding the cosmos and humanity’s place within it. His translation fueled the Renaissance movement’s synthesis of classical philosophy, Christian theology, and esotericism, giving rise to a rich tradition of Hermetic study. Read our other article, The Kybalion and New Thought: Rediscovering True Hermeticism, for more about true Hermeticism.

Why Study the Corpus Hermeticum?

The Corpus Hermeticum is far more rooted in authentic Hermetic tradition than later reinterpretations like The Kybalion. Key reasons to prioritise its study include:

- Authenticity:

The Corpus Hermeticum provides a genuine account of Hermetic philosophy as understood in antiquity, dealing with profound questions about the divine, the universe, and the human soul. - Philosophical Depth:

Its dialogues explore themes such as the nature of God, the unity of the cosmos, and the spiritual ascent of the soul. These ideas resonate with Neoplatonic and Gnostic traditions, offering rich material for philosophical inquiry. - Historical Significance:

As a key text during the Renaissance, the Corpus Hermeticum influenced countless thinkers, including Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, and even the foundations of modern science through its emphasis on divine order. - Contrast with Modern Works:

Unlike The Kybalion, which simplifies and reinterprets Hermetic ideas through a New Thought lens, the Corpus Hermeticum reflects the intellectual and spiritual rigour of its time, making it a more reliable source for serious study.

Experts on the Corpus Hermeticum

The enduring value of the Corpus Hermeticum has been affirmed by leading scholars and thinkers:

1. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499):

Ficino described the Corpus Hermeticum as containing divine wisdom, stating: — Preface to Ficino’s Latin translation of the Corpus Hermeticum.

“Hermes, the most ancient and learned of philosophers, has traced a direct path to the divine through the mind’s contemplation of the cosmos.”

2. Frances A. Yates (1899–1981):

In her groundbreaking work Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Yates highlighted the transformative impact of the Corpus Hermeticum:

“The Hermetic texts, as presented by Ficino, conveyed a sense of divine immanence, placing humanity in a cosmos suffused with the divine and filled with possibilities for spiritual ascent.”

3. Brian Copenhaver:

A modern authority on the Hermetica, Copenhaver’s translations and commentaries emphasise their philosophical richness: — Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation.

“The Corpus Hermeticum is a dialogical journey that engages the reader in the process of self-realisation, merging the divine and human in a unity that transcends time.”

The Renaissance Legacy

The Latin translation of the Corpus Hermeticum by Marsilio Ficino was instrumental in its preservation and dissemination. Ficino’s work, alongside the subsequent writings of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and other Renaissance scholars, established Hermeticism as a central pillar of Western esoteric tradition. These humanist thinkers regarded the Corpus Hermeticum as a bridge between ancient wisdom and the Christian faith, blending the two into a harmonious worldview.

For those seeking a true understanding of Hermetic philosophy, the Corpus Hermeticum remains the definitive source. Its depth, authenticity, and historical importance far surpass works like The Kybalion, which reflect modern reinterpretations rather than ancient teachings. By engaging with the Corpus Hermeticum, readers can explore the profound mysteries of the cosmos, the divine, and the human soul as they were originally envisioned—free from the distortions of later adaptations. For more information, read Corpus Hermeticum and The Kybalion: Practical Applications and Insights.

An Author of The Great Book or Just a Manufactured Legacy

William Walker Atkinson’s The Kybalion and subsequent works like The Seven Cosmic Laws exemplify a pattern of rebranding and commodification of spiritual concepts. Through his use of pseudonyms, he created the illusion of vast expertise while recycling borrowed ideas. Far from a Hermetic masterpiece, Understanding The Kybalion only reflects early 20th-century spiritual trends and Atkinson’s knack for marketing rather than authentic ancient wisdom. As the mystique fades, his legacy as a writer is increasingly seen as opportunistic and derivative. An internet blog to check out. Click here.

Bibliography and Corpus Hermeticum literature

- Copenhaver, Brian P. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Ficino, Marsilio. De Doctrina Hermetica. Latin Translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, Florence, 1463.

- Yates, Frances A. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Fowden, Garth. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Atkinson, William Walker. The Law of the New Thought: A Study of Fundamental Principles and Their Application. Chicago: Progress Company, 1902.

- The Three Initiates. The Kybalion: Hermetic Philosophy. Chicago: The Yogi Publication Society, 1908.

- Atkinson, William Walker. The Seven Cosmic Laws. Chicago: The Yogi Publication Society, 1912.

- Godwin, Joscelyn. The Theosophical Enlightenment. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.