The Virgin and the Double-Headed Eagle: Freemasonry, Iconography, Prophecy, & Imperial Theology

Introduction

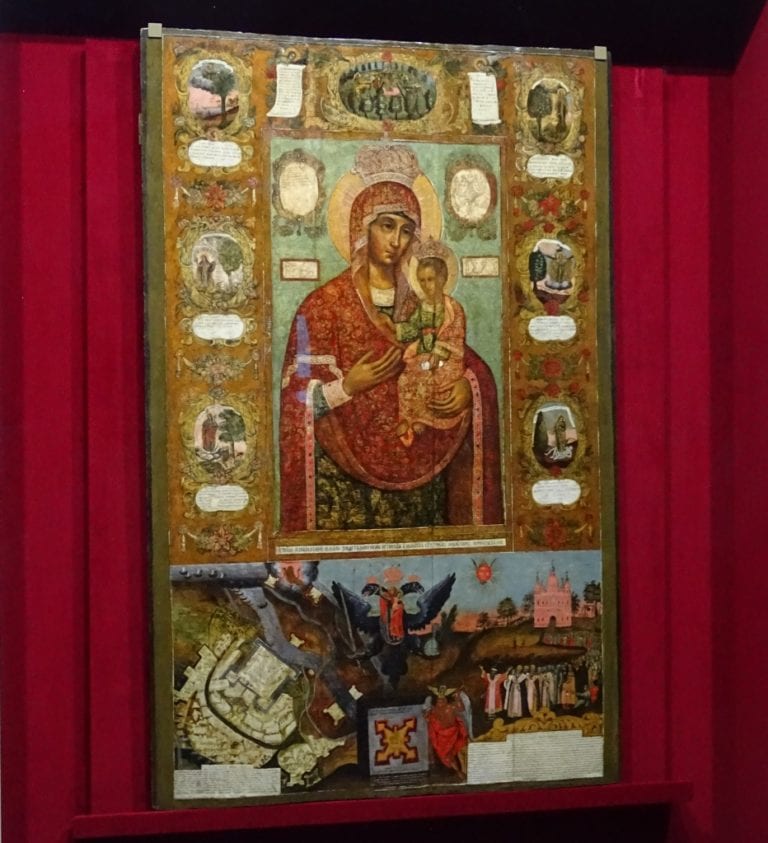

Throughout the history of Eastern Christianity, icons have served not merely as artistic devotions but as theological revelations rendered in image. Among the more enigmatic and prophetic of these visual theologies are two nearly forgotten icons from late Imperial Russia: Wings Like an Eagle and Autocratic. Commissioned in the final decades of the Romanov dynasty and housed in the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord in Verzilovo, these icons uniquely depict the Virgin Mary enthroned or borne aloft by the double-headed eagle—an image that fuses Mariological symbolism, imperial legitimacy, and eschatological expectation.

These two icons emerged at a moment of great cultural anxiety and spiritual tension in Russian society. As pressures against autocracy mounted and modern secular ideologies challenged the Orthodox worldview, the sacred function of monarchy was not only defended but sacralised. These icons, painted by an unknown hand under the patronage of the Shakhovskoy princes, were not simply commemorative works—they were visual sermons, prophetic signs, and theological assertions about the divine role of the Orthodox emperor in upholding the faith.

The icon Wings Like an Eagle draws directly from Revelation 12:14, wherein the woman (interpreted as the Church) is given the wings of a great eagle to flee from the serpent. In parallel, the icon Autocratic shows the Virgin enthroned upon the imperial eagle itself, a clear assertion that true Orthodoxy stands only when supported by divinely anointed monarchy. Both icons, though rooted in biblical typology, are unmistakably Russian in their imperial iconography and ecclesiological message.

This article will examine the historical context of these icons, analyse their theological and symbolic elements, explore their scriptural foundations, and engage with key voices such as Nikolai Zhuravlev and the pre-revolutionary scholar V. Borin. In doing so, we argue that these images offer more than a glimpse into the devotional life of late Imperial Russia—they stand as prophetic artefacts whose message may yet speak to the spiritual destiny of the Orthodox Church in exile and in hope.

Freemasons are included in this article because their symbolic use of the double-headed eagle forms a curious and revealing parallel to its Orthodox and imperial meanings. Although the Freemasonic double-headed eagle first appeared in France around 1761–1763 within the Chevalier Kadosh degree, its earliest promoters had strong ties to Russia—suggesting that imperial Russian symbolism may have influenced its adoption in Masonic iconography. In this context, what was once an emblem of divine sovereignty and Church authority in Byzantine and Russian tradition was reinterpreted in Masonic high grades as a symbol of esoteric power, inner ascent, and transnational hierarchy. Understanding this transformation offers critical insight into how sacred imperial symbols were appropriated, recast, and exported into a radically different ideological framework.

The Virgin and the Double-Headed Eagle: Historical Origins and Royal Patronage

At the close of the 19th century, amid the waning decades of Imperial Russia and increasing pressures against the Orthodox monarchy, the noble House of Shakhovsky undertook a unique artistic and spiritual project. This noble family, whose estate in Verzilovo had historical ties to the defence of Orthodoxy and Tsarist ideals, commissioned two extraordinary icons—Wings Like an Eagle and Autocratic—as acts of devotion and imperial affirmation. The icons were painted by an unknown yet clearly skilled iconographer and were intended to express the sacred relationship between the Mother of God, the Orthodox Church, and the Tsar. Unlike typical Marian icons of the period, these compositions introduced a startling and prophetic motif: the Theotokos supported, enthroned upon, or lifted by the double-headed eagle of Byzantium—long since adopted by the Russian Empire as its heraldic emblem. The eagle, bearing two crowns and a central imperial coronet, was more than a political symbol—it was understood in Orthodox theology to signify the divine order of Church and Empire acting in unity.

The Virgin and the Double-Headed Eagle icons were enshrined in the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord in the village of Verzilovo, located in the Stupino District of the Moscow Region. This Church, which once stood at the centre of the Shakhovsky estate, became not only a local site of worship but a symbolic sanctuary of imperial theology during a time of cultural instability. A significant moment in the history of these icons occurred in 1896, when Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna visited the Shakhovsky estate. In honour of their coronation, they presented a precious oil lamp to the Church, inscribed with the enamelled dedication: “In honour of the coronation of Nicholas and Alexandra. 1896.” The lamp was placed directly in front of the Wings Like an Eagle icon, and its oil was later used by the faithful for anointing. Because of this gift, and due to the special reverence of the monarchs themselves, the Church of the Transfiguration was soon regarded by locals as a “Royal” temple—an unofficial sanctuary of the Tsar’s sacred presence and blessing.

The 20th century, however, would not be kind to such relics of Orthodoxy and monarchy. Following the Revolution and the decades of Soviet repression, the icons fell into obscurity. But in the summer of 2003, both were rediscovered by Orthodox believers. Devotees made photocopies and began to distribute them across Russia, initiating a revival of interest in the iconography and its theological message. That same year, a copy of the Autocratic icon was reported to have streamed myrrh during a service held in honour of St. Seraphim of Sarov in the Nizhny Novgorod Diocese. The phenomenon repeated itself on August 12 at the grave of Hieromonk Vladimir (Shikin) in Diveyevo, on the birthday of the Tsarevich Alexei. These events sparked renewed veneration and were seen by many as signs from heaven affirming the sanctity of the Royal Martyrs and the theological truth encoded in the icon. The faithful responded with pilgrimages, processions, and icon installations. A large copy of the Autocratic icon was enshrined at the Resurrection Monastery of New Jerusalem in the village of Sukharevo—an area where reverence for the murdered Imperial Family remains particularly strong.

However, this quiet revival was soon disrupted. In the spring of 2004, despite the growing popular devotion and four years after the official glorification of the Royal Martyrs by the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Juvenal (Poyarkov) ordered the removal of the original icons and the royal lamp from the Verzilovo church. He also replaced the parish’s leadership. This action, which believers interpreted as ecclesiastical censorship or a modern-day iconoclastic act, caused shock and sorrow among monarchist Orthodox Christians. For them, the removal of the icons was not merely administrative—it was spiritual betrayal at a time when prophetic images were beginning to reawaken the conscience of the Church. To this day, the whereabouts of the original icons remain uncertain. Yet the theological and eschatological message they carry has not been silenced. Through surviving copies and growing popular interest, Wings Like an Eagle and Autocratic continue to speak, reminding Russia—and the world—of the sacred link between the Mother of God, the persecuted Church, and the divine promise of restoration through an anointed Orthodox ruler.

Iconographic Structure and Orthodox Symbolism

The two icons Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle form a theological diptych, portraying not only the Theotokos and Christ Child in a political-theological context, but also mapping the spiritual destiny of the Church as bound to the fate of the Orthodox monarchy. While both icons centre on the Virgin and Child, their posture, symbols, and liturgical environment offer distinct theological meanings—one portraying the glory of established sacred empire, the other the protective exile of the Church in apocalyptic times.

The Autocratic Icon

The Autocratic icon presents a majestic vision of the Theotokos enthroned upon the imperial double-headed eagle, the ancient symbol of Byzantine sovereignty adopted by the Russian Empire. With its dual gaze to East and West, this eagle signifies both dominion and vigilance, echoing the Orthodox vision of the Tsar as the earthly vicegerent of God, safeguarding the unity of Church and State. The Mother of God is shown robed in deep royal porphyry, a colour traditionally reserved for emperors and high Byzantine officials, highlighting her status as Queen of Heaven. Upon her head is an imperial crown, and in her hand she holds the sceptre, symbolising divine authority. Unlike more common depictions of the Virgin in repose, here she reigns actively, her posture upright and commanding, making her not only a maternal figure but an empress of sacred destiny.

The Christ Child sits upon her left arm and blesses with both hands—a gesture usually associated with episcopal authority. This dual blessing links Christ to the idea of divine kingship and priesthood in one, and according to Orthodox theology, serves as a visual affirmation of the unity of spiritual and temporal power under divine law. Flanking this exalted throne are four carefully chosen saints: Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor and archetype of the Orthodox ruler, Thekla of Iconium, protomartyr and equal to the apostles, representing steadfast virginity and missionary witness, Sergius of Radonezh, the great ascetic and spiritual reformer of Russia, and Varlaam of Khutyn, a protector of the land and monastic life. Their presence ties together imperial power, apostolic faith, ascetic holiness, and national sanctity—encapsulating the theological vision of “Holy Russia.” The eagle on which the Virgin sits does not rest on mere earth but upon the “Stone of Faith,” an apparent biblical reference to Christ as the cornerstone (Mark 12:10; Psalm 118:22). In this configuration, the throne becomes an extension of Christ’s foundation, suggesting that imperial authority must be rooted in the Logos to be legitimate. It is not secular autocracy, but theocracy in its highest Orthodox conception.

The Wings Like an Eagle Icon

The second icon, Wings Like an Eagle, portrays a very different but intimately related vision. Here, the Theotokos does not sit but stands, upright and alert, carrying the Christ Child in her arms and holding a flowering branch—traditionally interpreted as a symbol of peace, messianic fulfilment, and the promised return of a righteous Orthodox Tsar. Unlike Autocratic, this icon does not represent enthronement, but exile—yet not a hopeless one. The double-headed eagle beneath her feet no longer serves as a stationary throne. It becomes a living, dynamic creature, soaring through space and lifting the Mother and Child into the sky. This imagery directly invokes Revelation 12:14: “And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place…” In Orthodox interpretation, the “woman” is the Church—often understood as both the mystical bride and the image of the Theotokos—preserved during tribulation by divine providence. The eagle thus becomes a symbol not of conquest but of deliverance. It is not the empire in glory, but the empire in hiding—the secret protection of the remnant, the flight into the inner wilderness where sanctity is preserved in anticipation of eschatological restoration.

Zhuravlev’s interpretation of this icon is deeply symbolic and grounded in prophetic theology. He writes:

“She stands, not sits… the triumph of this salvation is granted to the Church through the power of the royal eagle’s wings.”

This posture of standing, rather than seated enthronement, suggests vigilance, watchfulness, and readiness. It portrays the Church not as triumphant in the world, but as active and preserved by divine grace. The Christ Child, again blessing with both hands, reinforces the notion that the divine monarchy has not vanished—it is being guarded until the appointed time. Taken together, these two icons form a visual theology of time: Autocratic depicts the Church as it was meant to be—enthroned in harmony with the divine monarch; Wings Like an Eagle portrays the Church as it must be—hidden, protected, carried away in faith until the restoration. In this, the double-headed eagle becomes both throne and wings, empire and exile, symbol and prophecy—uniting the terrestrial and the celestial under the protection of the Virgin and the authority of her divine Son. Saint Seraphim of Sarov’s prophecy is central to this theology: “The Lord shall bless His people with peace and exalt the horn of His Anointed David… the Most Pious Sovereign Emperor… whom His holy right hand shall strengthen over the Russian land.”

Scriptural Foundations: Revelation, Daniel, and 3 Ezra

To fully grasp the theological and prophetic force of the Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle icons, one must turn to the apocalyptic texts of Scripture that lie at their heart. These icons are not merely ornamental depictions of imperial piety—they are visual commentaries on Scripture, rendered with eschatological urgency and national significance. Their composition draws directly from three key scriptural sources: the Book of Daniel, the Revelation to Saint John the Theologian, and the lesser-known yet profoundly influential 3 Ezra (also known as 2 Esdras in the Vulgate tradition), a text revered in Eastern and Russian apocalyptic traditions.

Daniel 2: The Stone Not Cut by Human Hands

In the Book of Daniel, the prophet interprets the dream of King Nebuchadnezzar, who sees a statue composed of four different metals representing successive world empires. The vision concludes with the arrival of a mysterious stone, “cut out without hands,” which strikes the feet of the statue, shattering it. This stone then becomes a great mountain and fills the entire earth (Daniel 2:34–35). Orthodox theology has long interpreted this stone as Christ and His Kingdom—the unshakable reign of God that dismantles the transient powers of human empire. Yet in Russian imperial theology, this vision also held national implications.

The mountain was often likened to the Church in its fullness, grounded not only in the spiritual headship of Christ but also in its historical manifestation through Orthodox monarchy. The stone “cut without hands” became a symbol not only of divine origin but of prophetic inevitability—the emergence of a holy people under sacred rule who would inherit the broken kingdoms of the world. The icon Autocratic, with the eagle enthroned upon the “Stone of Faith,” visually embodies this prophecy. The eagle represents the imperial protector, while the Virgin and Child signify the incarnate Logos and the Church upheld by divine order. The mountain in Daniel becomes both the Church Militant and the mystical Zion, awaiting full manifestation in history.

Revelation 12: The Woman and the Eagle’s Wings

The icon Wings Like an Eagle takes its central inspiration from the twelfth chapter of the Apocalypse of Saint John. In that vision, a woman “clothed with the sun” gives birth to a male child destined to rule the nations with a rod of iron. As the dragon seeks to destroy her, she is given “two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time” (Revelation 12:14).

In patristic and Orthodox interpretation, the woman is understood as the Church, and the wilderness as the state of exile and tribulation in the latter days. The great eagle’s wings represent divine assistance—both spiritual and, in the Russian tradition, political. Within this framework, the eagle is not merely an allegory of God’s providence but is historically embodied in the figure of the Christian emperor, who preserves the Church during apostasy and persecution.

The Wings Like an Eagle icon thus becomes a prophetic image of Holy Russia as the Church in exile, not vanquished but preserved. The Virgin, bearing Christ, is not enthroned but in flight—signifying that the Church, though driven into the wilderness, remains inseparable from divine mission and protection. The flowering branch in her hand is a visual echo of Isaiah’s “rod from the stem of Jesse,” interpreted here as a future Tsar—an anointed one who will emerge in the fullness of time.

3 Ezra 13: The Man from the Sea and the Mountain

A less commonly referenced but highly influential text in Russian apocalyptic thought is 3 Ezra (also known in Slavonic as 2 Esdras), particularly chapter 13. Here, the seer describes a vision of a solitary man rising from the sea, carving out a great mountain without human hands, and standing upon it. This messianic figure gathers a multitude of peaceful people to himself, following the defeat of many hostile nations. Russian theological writers from the 17th century onward interpreted this mountain—uncut by hands and created in the end times—as the renewed Orthodox monarchy.

Zion was not merely spiritual but also had a historical embodiment: the Christian Empire purified, restored, and gathered around the Anointed One. The connection to the stone of Daniel 2 is immediate, and the two visions—Daniel’s and Ezra’s—were often read together in imperial theology. In the context of the icons, especially Autocratic, this imagery takes full form. The Christ Child blesses with the bishop’s sign, echoing the idea found in 3 Ezra that the messianic figure will hold both spiritual and temporal power. Zhuravlev connects this explicitly to the concept of Orthodox kingship: the emperor does not perform sacramental rites, but he holds a sacramental role in preserving Orthodoxy and ensuring right belief.

Imperial Blessing and Ecclesial Authority

The Christ Child in both icons offers a two-handed episcopal blessing, a gesture typically reserved for bishops. This symbolism was not lost on Orthodox commentators. According to Canon 104 of the Council of Carthage, a righteous emperor holds a “hierarchical dignity,” functioning as protector of the Church even if he is not a cleric. Likewise, Article 64 of the Russian Empire’s Fundamental Laws stated: “The Emperor, as a Christian sovereign, is the supreme defender and guardian of the dogmas of the dominant faith and the custodian of every good order in the Holy Church.”

Zhuravlev highlights this union of ecclesiastical and imperial roles not as a fusion of Church and state in the modern sense, but as a harmony under divine governance. In his words, the emperor is “a living icon of Orthodox kingship,” just as the Virgin is a living icon of the Church. Together, these scriptures—Daniel, Revelation, and 3 Ezra—form the theological scaffolding upon which the icons of Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle are built. They proclaim that while the Church may be hidden in the wilderness, it is not abandoned. Carried on the wings of God’s providence, it awaits the time when the mountain will again rise, and the Anointed One will rule with justice and peace.

The Azov Icon and V. Borin’s Imperial Commentary

To understand the origin and meaning of the 19th-century icons Wings Like an Eagle and Autocratic, one must trace their iconographic lineage to an earlier and deeply significant prototype: the Azov Icon of the Mother of God. This lesser-known icon emerged during a pivotal era in Russian history and, as pre-revolutionary historian V. Borin demonstrates, served as both a theological affirmation and a political proclamation. The Azov Icon is believed to have originated shortly after the Russian military campaign of 1696, when General Aleksei Shein and Tsar Peter I captured the Azov Fortress from the Ottoman Empire. This victory was hailed not only as a military triumph but as a divine sign of Russia’s rising destiny as the new defender of Orthodox Christianity. In response, the icon was likely created to commemorate this moment of imperial glory, and its composition reflects that ambition.

Borin’s careful study of the icon reveals a layered history. Originally a bust-length image, the icon was later expanded into a full-length depiction during the reign of Empress Catherine II in the second half of the 18th century—an era marked by renewed political interest in Azov and a flourishing of imperial theology. Borin notes that at least three successive layers or “records” can be discerned beneath the current composition, showing an evolution in meaning and form over time. The final result is a highly symbolic icon rich in theological and political narrative. In the Azov Icon, the Theotokos is portrayed above a colossal double-headed eagle—the state emblem of Russia since the fall of Byzantium—positioned over the Sea of Azov. A lion appears nearby, symbolically paired with a serpent, invoking Psalm 90:13: “Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.” The sea beneath her feet, the imperial eagle, and the lion-serpent imagery together declare divine dominion over chaos, false religion, and foreign enemies. Above her, God the Father and the Holy Spirit, depicted as a dove, affirm the Trinitarian framework of Orthodox salvation history.

Monastic saints, including those of the Kiev Caves—Anthony, Theodosius, Alypius, Moses the Hungarian, Prochorus, and Mark—are shown in prayerful veneration. Their inclusion reinforces the icon’s spiritual gravitas and links the military triumph to ascetic and ecclesial piety. Below, the mounted figure of the victorious Christian Tsar tramples the serpent with a lance, echoing the motif of Saint George and again affirming the Tsar’s divinely sanctioned role as warrior and protector of the faith. Borin and subsequent commentators, including Nikolai Zhuravlev, recognise the Azov Icon as a theological and iconographic predecessor to both Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle. Indeed, many of the structural elements and themes appear in these later icons: the Virgin elevated by or enthroned upon the imperial eagle, the Christ Child as blessing sovereign, the inclusion of saints who symbolise Russia’s spiritual history, and the message of preservation, triumph, and prophetic promise.

Zhuravlev further connects the Azov Icon to the vision of Revelation 12, seeing the double-headed eagle as the very wings granted to the woman (the Church) to flee into the wilderness. In his reading, the sea below the eagle is the world of fallen nations—the lion is the preserved remnant of Davidic kingship—and the eagle, as the tsarist guardian, becomes the active agent of God’s protection. This theological synthesis is deeply Russian, drawing upon patristic sources, medieval hagiography, and apocalyptic texts—most notably Daniel and 3 Ezra. Moreover, Zhuravlev points out that the mountain seen in 3 Ezra, “not cut by hands”, becomes a symbol of the Church and of Zion. Just as the Azov Icon places the Virgin atop the imperial eagle above the sea, the later icons of Verzilovo place her firmly on the “Stone of Faith,” affirming that the monarchy, when faithful, becomes the visible instrument of divine shelter for the Church. These are not metaphors of abstract piety—they are expressions of Orthodox theocracy as both mystery and mission.

In this way, the Azov Icon is not merely a historical relic but a prophetic anchor. It foreshadows the entire visual and theological program of the Wings Like an Eagle and Autocratic icons. Through its imagery, the imperial eagle becomes a vehicle of eschatological hope, linking past victories to future deliverance, and serving as a visible pledge of the Church’s endurance through divine monarchy. For Borin, and for those Orthodox commentators who followed him, these icons were not accidents of devotional creativity. They were revelations—written in gold and pigment, in mountain and sea, in eagle and Virgin—that the Church, though persecuted or hidden, remains carried on the wings of divine promise until the day when the Tsar shall return and Zion shall be seen once more.

The Persecuted Icons and the Faithful Remnant

Among the most powerful religious images to re-emerge in Russia’s post-Soviet spiritual awakening are the icons known as Autocratic (Russian: Самодержавная) and As an Eagle’s Wings (Яко крыля орла). These icons, both painted at the end of the 19th century and originally housed in the Church of the Transfiguration on the estate of the Shakhovsky princes in Verzilovo, bear a unique message: that true Orthodoxy is inseparable from sacred kingship, and that the double-headed eagle—symbol of both Byzantine and Russian sovereignty—is not merely heraldic, but profoundly theological. The Autocratic icon depicts the Theotokos enthroned on the imperial eagle, robed in royal porphyry and crowned, with the Christ Child seated on her left arm, blessing with both hands. Saints Constantine the Great, Thekla of Iconium, Sergius of Radonezh, and Varlaam of Khutyn flank her throne. The eagle stands upon the “Stone of Faith,” an allusion to Christ, the cornerstone rejected by the builders (Mark 12:10). The Virgin’s sash is shaped as a cross, indicating the Christian’s call to be crucified with Christ in loyalty to the sacred autocracy. A rainbow crowns the image, symbolising divine reconciliation and eschatological peace. In As an Eagle’s Wings, inspired directly by Revelation 12:14, the Theotokos stands upon the eagle’s back, holding the Christ Child and a paradise lily—a sign of the coming Orthodox Tsar.

The eagle lifts her into the wilderness, fulfilling the prophecy: “And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place.” Here, the Church is portrayed as both persecuted and protected—hidden yet triumphant. These icons, once venerated in the royal chapel by Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra (who gifted a coronation lamp placed before the icon), were preserved through revolution and atheistic persecution. But in 2004, despite increasing veneration among the faithful and reports of miraculous signs—such as myrrh-streaming, fragrance, healings, and visible phenomena—Metropolitan Juvenal of the Moscow Patriarchate ordered their removal, along with the lamp, and replaced the rector of the Verzilovo church. Many believers saw in this act not a theological correction, but a continued persecution of Russia’s monarchic soul. “This was not the 1930s,” one pilgrim observed, “but four years after the canonisation of the Royal Martyrs.” Nonetheless, copies of these icons proliferated. From 2003 onward, pilgrims carried them across Russia—from Moscow to Diveevo, from Lokot to Minsk. Myrrh flowed not only from the painted surfaces but even from prayer cards and prints. In one extraordinary instance, only the words “Save, Mistress, Holy Russia” were anointed with myrrh on the reverse side of a printed hymn. Believers reported visions, including that of Tsar Nicholas II holding the icon in his hands. During processions, the icons would appear to halt mysteriously, radiate fragrance, or manifest rainbows and other signs in the sky.

Their message is clear: the double-headed eagle is not merely an imperial symbol, but the bearer of the Woman clothed with the Sun, the Church taken into the wilderness. In these icons, the Tsar is not simply a political figure, but the “male child” born of the Church who is to shepherd the nations with a rod of iron (Rev. 12:5). The eagle bears not only sceptres and crowns, but the eschatological hope of Holy Russia. As Fr. Andrei Gorbunov and Hierodeacon Abel have written, the vision of the Woman and the Eagle is not abstract mysticism but a real spiritual geography—Russia as the desert where the Church is preserved until the time appointed. Despite ecclesiastical resistance, these icons are cherished as living testimonies of the Theotokos’ intercession and the enduring mission of the Orthodox Tsar. Their survival through iconoclasm, their defence by the “little flock,” and their miraculous signs are understood by many as providential. As Sergei Fomin concludes in his work And to the Woman Were Given Two Wings, the day will come when these icons will be canonically recognised and liturgically celebrated—as signs of the Divine Protection over Russia, and of the crowned destiny yet to be fulfilled.

The Ancient Origins of the Double-Headed Eagle

The image of the eagle, particularly in its double-headed form, is one of the most enduring and multifaceted symbols in world history. From ancient Anatolia to Byzantium, from imperial Rome to Christian iconography, it has signified majesty, sovereignty, and spiritual authority. Though today it is often associated with Orthodox Christianity and imperial heraldry, the double-headed eagle’s roots stretch deep into the ancient Near East and classical world. The earliest known representations of a double-headed bird appear in the archaeological record of the Hittites, who flourished in Anatolia between the twentieth and thirteenth centuries BCE. Cylinder seals from the former Hittite capital of Boğazköy (Hattusa), dated around 1750 BCE, clearly show an eagle with two heads and outstretched wings. Monumental reliefs from Alaca Höyük and Yazılıkaya depict the same form within religious contexts, suggesting the creature functioned as a divine guardian or sacred being.

These depictions likely reflected early religious dualism or the concept of divine omniscience—symbolised through the two heads facing opposite directions. This image later disappeared with the decline of the Hittite Empire, but it resurfaced more than a millennium later in the same geographical region under the Seljuk Turks. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, centred in Konya and Nicaea during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, adopted the double-headed eagle as a powerful courtly and architectural emblem. Under rulers such as Alaeddin Keykubad and Keyhusrev II, the image appeared on mosque decorations, textiles, carved stonework, and Qur’an stands. Scholars have noted that the Seljuks may have inherited the motif from earlier Sasanian and Byzantine traditions or adapted older Turkic and mythological imagery, including the ancient motif of the two-headed rooster (Jean-Pierre Digard, Dictionnaire de l’Islam, Paris: PUF, 1991).

Byzantium, heir to the Roman imperial tradition, integrated the eagle even more explicitly into its ideology. The Roman eagle (aquila), used since the time of the Roman Republic, had been a military standard carried by each legion and was associated with Jupiter, king of the gods. Roman emperors came to be seen as semi-divine figures, and the eagle was adopted as a symbol of the deified soul’s ascent to heaven. Suetonius records that during the apotheosis of Augustus, an eagle was released from his funeral pyre to signify his soul’s flight to the gods (The Twelve Caesars, Augustus 100.4). In Byzantium, the eagle took on even greater theological weight. It was understood as both a continuation of Roman imperial sovereignty and a Christianized emblem of divine authority. The adoption of the double-headed version, likely under the reign of Theodore II Laskaris in the mid-thirteenth century, symbolised the unity of spiritual and temporal power—the emperor as both Caesar and high priest. The two heads were interpreted as facing East and West, encapsulating the empire’s universal reach and sacred mission. Orthodox ecclesiastical furniture, particularly lecterns, often bore the image, closely resembling earlier Seljuk designs, indicating a cross-cultural exchange of sacred iconography (cf. Alain Besançon, L’image interdite: Une histoire intellectuelle de l’iconoclasme, Paris: Fayard, 1994).

From Byzantium, the double-headed eagle passed to the Slavic Orthodox world. It became a principal emblem of the Serbian Nemanjid dynasty and later of Muscovite Russia, which proclaimed itself the “Third Rome.” Ivan III formally adopted the emblem after marrying Zoe (Sophia) Palaiologina, niece of the last Byzantine emperor, thereby claiming spiritual and dynastic inheritance. Medieval Western Europe also encountered the double-headed eagle, often indirectly. Romanesque churches such as those in Vouvant, Moissac, and Civray include sculptural representations of the symbol, likely derived from imported Eastern fabrics and tapestries. Emile Mâle’s research on medieval iconography confirms that many motifs used in Romanesque art were borrowed from Persian or Byzantine textiles brought through Venice and the Crusader routes (L’Art religieux du XIIe siècle en France, Paris: Armand Colin, 1922).

A striking example of this transmission is the discovery of the “Shroud of Saint-Front” in Périgueux Cathedral, a fragment of 11th–12th century silk featuring a double-headed eagle, possibly woven in a Seljuk or Andalusian workshop. Such relics were often used as episcopal vestments or altar cloths and later copied into local art, further embedding the motif into Western Christian aesthetics. In Western heraldry, the eagle came to symbolise noble authority and martial prowess. Although the single-headed eagle was more common, the double-headed version gained prominence from the late twelfth century onward. Templar commander Guillaume de l’Aigle used it on his seal in 1227, followed by others such as Jocelin de Chanchevrier and Bertrand du Guesclin. The eagle also became the emblem of the Canons of Saint Anthony, depicted as black, crowned, and bearing a blue tau cross on its chest—an unmistakable fusion of imperial and ecclesial meanings.

By the early fifteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperors, beginning with Sigismund, adopted the double-headed eagle as their official heraldic device, distinguishing the emperor from lesser monarchs. By the end of the eighteenth century, the image had entered the arms of over 500 European noble families, with full prominence in 200 of them. The endurance and adaptability of the double-headed eagle over millennia demonstrate its potent visual appeal and ideological flexibility. Whether guarding temples, crowning emperors, or adorning altars, the eagle represents a complex synthesis of divine favour, imperial mission, and sacred order—qualities that would later be echoed, and sometimes altered, in Masonic and esoteric traditions.

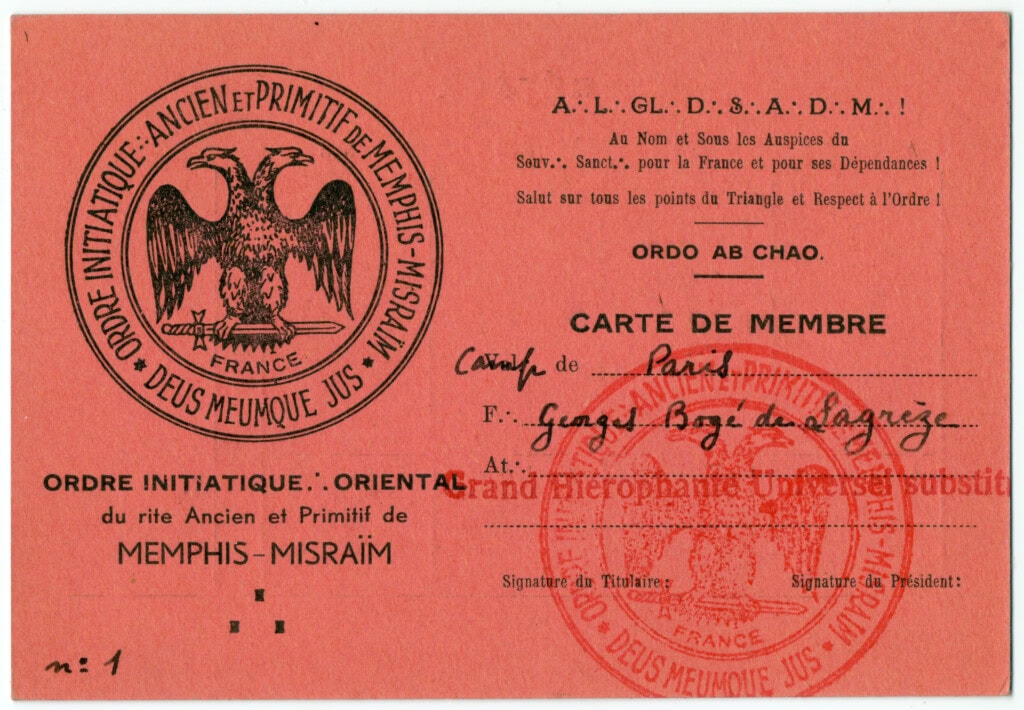

Esoteric Appropriation: Freemasonry and the Double-Headed Eagle

While the double-headed eagle emerged in ancient religious and imperial contexts, its most striking modern appropriation occurred within Freemasonry—particularly in the development of high-grade systems such as the Scottish Rite and the Rite of Memphis-Misraïm. From the mid-18th century onward, the eagle was adopted not only as a heraldic emblem of rank and initiation, but as a central symbolic key to the esoteric worldview professed by these rites. The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite (Rite Écossais Ancien et Accepté) is today the most globally practised system of high degrees in Freemasonry. Initially rooted in a strong Judeo-Christian esoteric tradition, this Rite evolved over two centuries into a structure proclaiming a universalist spirituality. From its inception, the choice of the double-headed eagle as its central emblem indicated an aspiration to timeless and borderless authority. As one historian of iconography observes, “the eagle, together with the dragon, is the only animal that belongs to the emblematics of all times and all peoples.”

When Freemasonry began integrating Western symbolic heritage in the second half of the 18th century, the eagle—with its ancient, imperial, and sacred connotations—naturally took its place among the fraternity’s most revered images. Within the Scottish Rite, it became most closely associated with the 30th degree: the Grand Elected Knight Kadosh (Grand Élu Chevalier Kadosh), also known as the Knight of the Black and White Eagle. The symbolism of this degree is suffused with dualism: the ritual hall is divided between a black western and a white eastern side; the jewel of the degree features a double-headed eagle, one head black, the other white; opposing pursuers—one destructive, one spiritual—test the candidate and the aspirant must pass beyond the realm of binary opposition. The eagle thus becomes the supreme symbol of transcendence over contradiction, echoing the Masonic motto Ordo ab Chao—order from chaos.

In an official letter from 1761, the Masons of Metz described this 30th-degree emblem in detail:

“The small emblem [of this grade] is a golden eagle displayed, wearing a prince’s crown on both heads and holding a dagger in its claws. The large emblem is a red eight-pointed cross, similar to that of Malta; at its center, within a circle, are a sword and dagger in saltire.”

This imagery was not abstract. As preserved in a 1763 seal from the Lodge of Saint John in Metz, the double-headed eagle was linked directly to themes of vengeance, justice, and remembrance of the Knights Templar. A surviving commentary by Meunier de Précourt—addressed to Jean-Baptiste Willermoz—reveals the esoteric teaching behind the symbol:

“The eagle holding a dagger in its talons with the words Neccum Adonay, Vengeance is God’s, represents the last words of Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Templars, when he summoned both Pope and King before God. A terrible summons, fulfilled by history.”

The eagle, in this view, is no longer only imperial—it is also initiatic. It represents those who survive catastrophe, who claim symbolic vengeance for injustice, and who rise like eagles to gaze into the sun—the truth that remains veiled to the uninitiated. The dagger gripped in the claws adds a militant edge, evoking not temporal war, but a metaphysical battle to restore a sacred order lost. The Rite of Memphis-Misraïm, often considered one of the most esoterically ambitious Masonic systems, also adopted the double-headed eagle prominently. Combining Egyptian, Hermetic, Christian, and Templar motifs, Memphis-Misraïm extended the symbolic reach of the eagle to encompass celestial vision, spiritual sovereignty, and the regeneration of lost wisdom. Unlike the Scottish Rite’s more structured hierarchy, Memphis-Misraïm drew deeply on mythological and initiatory sources, seeing in the eagle the convergence of ancient priesthoods and modern enlightenment.

The symbolic interpretation within Memphis-Misraïm frequently points to the eagle as the bird of light—linked to the solar mysteries, the watcher of the divine, and the protector of sacred mysteries. The eagle’s two heads, rather than representing dualism, can signify the unification of polarities: material and spiritual, East and West, past and future. Early Egyptian iconography, such as the Horus-falcon, influenced these interpretations. As the bird who flies highest and sees furthest, the eagle became the emblem of spiritual mastery and divine contemplation. In this tradition, it is not the throne of empire, but the chariot of ascension.

However, unlike in the Orthodox iconographic tradition—where the eagle is the liturgical vehicle of the Church and the seat of the Theotokos—the Masonic use transforms the eagle into an emblem of the initiated individual’s inner ascent. It ceases to be a throne and becomes a personal path. The emphasis shifts from ecclesial service to individual illumination. This adaptation marks a critical divergence. In Christian imperial theology, the eagle symbolises mission, sacrifice, and divine appointment. In the esoteric rites of Freemasonry and Memphis-Misraïm, it often symbolises the seeker’s own sovereignty, mastery over the elements, and participation in a hidden lineage of spiritual authority.

While both uses inherit the sacred weight of the eagle from Roman and Byzantine empires, their directions differ. The Orthodox eagle serves the Church and the Gospel. The Masonic eagle, especially in Memphis-Misraïm, serves the ideal of a universal, initiatic fraternity governed by inner gnosis and personal transformation. The result is a dual inheritance: a symbol once enthroned in cathedrals and imperial rites now reimagined in Masonic temples as the emblem of secret knowledge and esoteric kingship. Yet for the Orthodox tradition, the eagle remains not a sign of mystery, but of manifest destiny—of a divine Church, upheld by God, soaring toward the wilderness prepared in Revelation 12.

Russian Freemasonry and state power from Peter the Great to Alexander I

While Russian Freemasonry often mirrored European Enlightenment values—such as brotherhood, philanthropy, and mysticism—it developed in unique tension with the autocratic and Orthodox religious structures of Imperial Russia.

Origins and Early Growth

Freemasonry likely entered Russia through British and German contacts during the reign of Peter the Great. Legends claim he was initiated into a lodge during his 1698 travels, though documented Masonic activity only appears after 1731. Under James Keith, a Scottish Jacobite and general in Russian service, Freemasonry found its first structured expansion, bringing with it a spiritual, quasi-chivalric ethos.

Five Main Obediences (18th Century)

- English obedience led by Ivan Elaguine.

- Zinnendorf’s “Swedish-Berlin” system, more spiritual, introduced by Baron Reichel.

- Swedish Rite, brought by princes Kurakin and Gagarin, emphasised chivalric pageantry.

- Brunswick system, which had a more practical and charitable orientation.

- Rosicrucian-inspired mystical Freemasonry, focused in Moscow with figures like Novikov.

Influence of the Rosicrucians and Mystics

Figures such as Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin and Martinez de Pasqually greatly influenced Russian Masons. They viewed Freemasonry as a spiritual remedy for the void left by the weakened Orthodox Church, aligning Freemasonry with a sacred monarchy rather than opposing it.

The Double-Headed Eagle and Imperial Mysticism

In Russian Masonic symbolism, particularly in the Scottish and Rosicrucian rites, the double-headed eagle was appropriated from the imperial coat of arms, not as a political claim but to symbolise spiritual authority and mystical sovereignty. The eagle symbol was interpreted as a “reconciler” of spiritual and temporal powers: one head looked to the spiritual East, the other to the temporal West. Freemasonry in Russia developed a mythic language wherein the Tsar could be seen not only as political ruler but as a mystical figure, echoing Byzantine and Orthodox traditions.

Tensions and Suppression

- Catherine II, fearing revolutionary influences and internal dissent, suppressed the lodges in the 1790s despite their loyalist rhetoric.

- Paul I, though influenced by Masonic ideals and the Knights of Malta, did not legalise the Order, although he released imprisoned Masons.

- Alexander I lifted the ban in 1802. Masonic activity thrived and took part in philanthropy and education, but concerns about their cosmopolitanism, deism, and possible liberalism resurfaced after the Napoleonic wars.

Final Phase (1825 and Beyond)

Despite their public declarations of loyalty to the Tsar (e.g., in the chanting of odes to Alexander I and rituals celebrating his reign), the Masons were again scrutinised. The Decembrist movement, composed in part of former Freemasons, revealed the risk of revolutionary sentiments percolating through secret societies. Consequently, Freemasonry was officially banned again after 1822.

Why the Double-Headed Eagle in Russian Freemasonry?

Imperial Legitimacy and Mystical Kingship: The Russian Masons saw the Tsar as the anointed ruler, divinely placed like the emperors of Byzantium. The double-headed eagle, a Byzantine inheritance, symbolised this sacral kingship—a union of spiritual and temporal powers. Esoteric Adoption: High-degree Masonic systems like the Scottish Rite and Rosicrucian circles adopted the eagle as a mystical emblem of dual vision, inner enlightenment, and divine guidance—linking heaven and earth, soul and state.

Russian Exceptionalism: For some elite Russian Masons, the empire represented a new spiritual centre, and the double-headed eagle became a messianic emblem, foreshadowing Russia’s role in guiding or preserving the sacred tradition of kingship in a post-Enlightenment world. Political Symbolism Masked by Ritual: Despite its mystical language, the use of the imperial eagle also functioned as a coded affirmation of Tsarist loyalty, a necessary shield for survival under authoritarian regimes.

The Virgin and the Double-Headed Eagle Conclusion: A Prophetic Icon for the Church in Exile

The icons Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle stand as more than artefacts of late imperial piety—they are theological manifestos painted in silence, prophecy preserved in gold and gesso. Rooted in Scripture, enriched by tradition, and born of a moment of political and spiritual crisis, these images bear witness to a unique synthesis of Orthodox ecclesiology, imperial theology, and apocalyptic vision. Their iconography reveals a profound duality. In Autocratic, the Church is enthroned in harmony with sacred monarchy, rooted upon the Stone of Faith, surrounded by saints and upheld by the eagle of empire. In Wings Like an Eagle, the Church is exiled yet preserved, hidden in the wilderness but carried by divine protection, awaiting the hour of return and vindication. One speaks of a visible reign; the other of a mystical preservation. Together, they form a theology of exile and expectation—a visual theology of the Church between the times.

The scriptural foundations drawn from Daniel, Revelation, and 3 Ezra position these icons firmly within the Orthodox understanding of sacred history. They do not merely reflect the past; they interpret the present and anticipate the future. In their imagery, the Virgin becomes not only the Mother of God but also the personification of the Church—both persecuted and glorified. The Christ Child is not merely the Incarnate Logos but also the ruler foretold, who will come again to judge and to restore. Historians like V. Borin and theologians like Nikolai Zhuravlev have shown that these icons draw upon deep rivers of Orthodox tradition, wherein empire is not idolised, but sanctified only insofar as it serves the truth. The double-headed eagle, when united with the Theotokos and the Church, becomes not a symbol of domination but of divine order—pointing to a sacred political reality that transcends modern categories.

In a time when many feel that the Church is once again in the wilderness—beset by secularism, divided by confusion, and haunted by the ruins of the 20th century—these icons remind us that she is not abandoned. She is carried. She is lifted by wings not of human power but of divine providence. And within her, the Child still blesses with both hands. Thus, Autocratic and Wings Like an Eagle are not relics of nostalgia, but icons of promise. They call to the Orthodox soul not to retreat in fear but to prepare in faith. For in the hidden Church there still beats the heart of the Empire of Christ, and from the wilderness may yet rise the stone that fills the whole earth.

Until that day, the icons remain—not merely to be venerated, but to be understood.

If you want to know more about the Virgin Mary, see our article, The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife, or if you want to know more about the Theotokos, we have a Virgin in Majesty dedicated magazine, Issue 11 (August 2024).

References

Russian and Orthodox Sources:

– Nikolai Zhuravlev, On the Icon of the Theotokos “Wings Like an Eagle”, Orthodox Brotherhood Publication, 2003.

A theological and eschatological analysis of the icon’s symbolism based on Revelation 12 and the Orthodox vision of monarchy.

– V. Borin, Étude sur l’icône d’Azov, unpublished pre-revolutionary manuscript.

Explores early Russian veneration of the eagle symbol in iconography tied to imperial military victories and Marian protection.

– S. Sablukov, Symbols of the Russian Imperial Throne, Saint Petersburg, 1907.

Covers the liturgical and political use of the double-headed eagle in relation to autocracy and Orthodoxy.

Historical and Iconographic Studies:

– Émile Mâle, L’Art religieux du XIIe siècle en France, Paris, 1922.

Traces the transmission of Eastern iconographic symbols, including the eagle, into Romanesque art and cathedral sculpture.

– Jean-Luc Leguay, L’aigle à deux têtes, histoire et symbolisme, Paris, 2010.

Comprehensive history of the eagle motif from Mesopotamian and Hittite seals to Byzantine and Christian imperial iconography.

– Hélène Ahrweiler, L’idéologie politique de l’empire byzantin, Paris, 1975.

Analyses the symbolic construction of imperial power in Byzantium, including the adoption and adaptation of the double-headed eagle.

Primary Masonic Sources and Interpretations:

– Paul Naudon, Les origines de la Franc-Maçonnerie, Paris, 1968.

Historical survey of Masonic systems and their symbolic inheritance, including the eagle as a late addition to higher degrees.

– Jacques Rolland, La symbolique maçonnique du REAA, Dervy, 2002.

Details the symbolic use of duality, polarity, and the black-and-white eagle in the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite.

– Meunier de Précourt, Correspondance avec Willermoz, cited in René Le Forestier, La Franc-maçonnerie templière et occultiste aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, Paris, 1914.

Discusses the meaning of the eagle in the Chevalier Kadosh degree as a symbol of justice and spiritual vengeance tied to the Templar legacy.

– Rituel manuscrit du Chevalier Kadosh, Archives de la Loge de Saint Jean, Metz, 1763.

One of the earliest surviving ritual documents associating the double-headed eagle with the highest degrees in French Masonry.

– Texts of the Rite de Memphis-Misraïm, 19th–20th c. French obediences.

Elaborates on the eagle’s symbolic connection to Hermetic ascent, dual vision, and spiritual sovereignty.