Three Faced God: Forbidden Image of the Holy Trinity

Vultus Trifrons, the Strange and Powerful Symbol of the Forgotten Trinity Icon the Church Tried to Erase

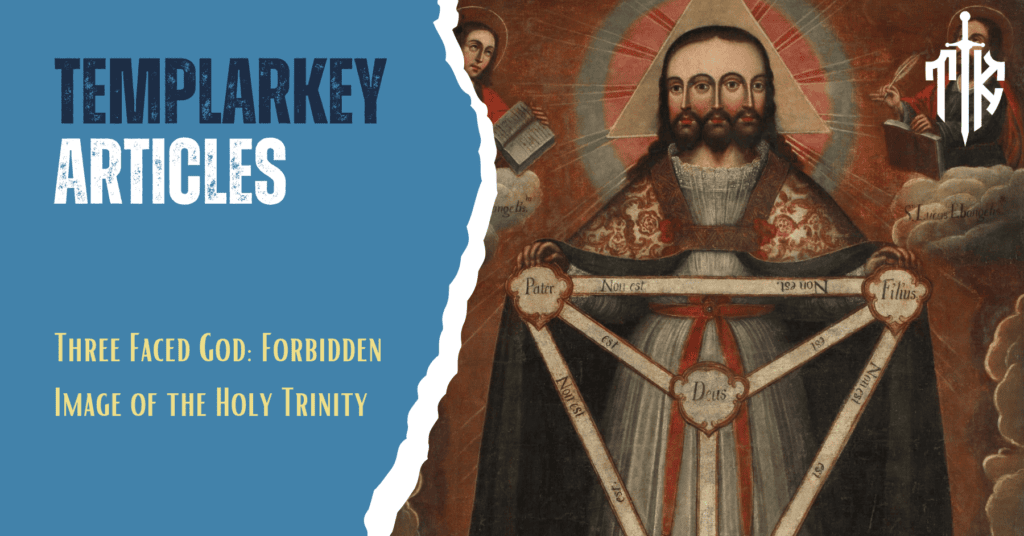

In a quiet corner of post-Reformation Europe, a controversial image was painted—one so powerful, so theologically charged, that it was later forbidden by papal decree. The Holy Trinity, portrayed not as three persons in distinct form, but as one divine figure with three human faces.

This 1620s Netherlandish painting doesn’t just defy modern sensibilities—it challenges the very boundaries of what could be depicted in Christian art. At its core is a profound message drawn from centuries of theology, mysticism, and sacred geometry. And yet, this image was officially silenced.

Today, we decode what it meant—and why it was ultimately erased from Church walls across Europe.

“This type of image, though sincere in its symbolism, was ultimately rejected because it created more confusion than clarity.”

— Dr. Jeffrey Hamburger, Professor of Art History, Harvard University

The Three Faced God: A Medieval Expression of Trinitarian Unity

The central motif of the three faced God, known as the Vultus Trifrons, once served as a visual metaphor for the deepest Christian mystery: one God in three persons.

This triple-faced representation appeared in illuminated manuscripts, woodcuts, and altarpieces, especially between the 14th and 17th centuries. It sought to express unity of substance while distinguishing the persons of the Father (Pater), Son (Filius), and Holy Spirit (Spiritus Sanctus).

“In this icon, the eye beholds what the intellect strains to grasp: one substance, three hypostases,”

— Prof. Jean-Michel Spieser, Université de Fribourg

Though striking, this symbol was not intended to be literal. It was a pedagogical and mystical representation—an attempt to translate the metaphysical doctrine of the Trinity into visual language.

Why the Catholic Church Eventually Forbade the Three Faced God / Trinity Image

By the mid-17th century, the Catholic Church formally banned the depiction of the Trinity as a three-faced figure, judging it theologically problematic and pastorally misleading.

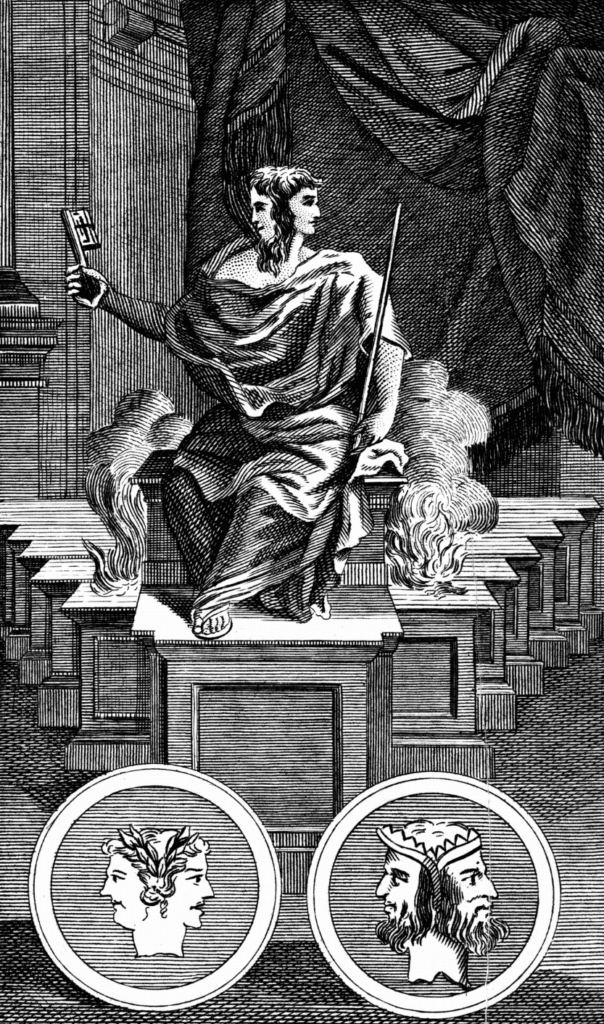

- Confusion with Pagan Imagery

The image resembled pagan gods like Janus, the Roman deity with two faces (god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings), suggesting polytheism or divine multiplicity. The Church feared this would blur the distinction between Christian monotheism and ancient mythologies.

- Risk of Heresy (Modalism)

The fusion of three persons into one form risked echoing modalism, a heresy condemned at the Council of Constantinople (381), which claimed the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were merely different “modes” or appearances of one divine person.

- Violation of the Doctrine of the Incarnation

According to orthodox doctrine, only the Son was incarnate. Depicting the Father and Spirit in human form undermined this distinction and muddied the understanding of the Incarnation.

- Distortion of Divine Simplicity

The image was perceived to distort the unity and simplicity of God by implying a composite being—something more monstrous than divine.

In 1628, Pope Urban VIII, through the Congregation of the Index, officially condemned such representations. Artists were instructed to use approved Trinity iconography: typically, the Father as an elderly man, the Son as Christ, and the Spirit as a dove—distinct, yet unified by light or gesture.

“It was not iconoclasm, but a corrective move—intended to preserve the integrity of Trinitarian theology.”

— Dr. Jeffrey Hamburger

For an extended study of similar Trinitarian images and their evolution across Christian Europe, see Templarkey Issue 6 (January 2023), where we further explore the visualised Trinitarian imagery also linked to the Knights Templars (this issue is a Templars in Portugal Special Edition) and the presence of this image in Portugal.

The forbidden image became a lost artefact, preserved only in private devotionals, hidden manuscripts, and rare surviving canvases—such as the one featured in this article. In addition to paintings and manuscript illuminations, Trinitarian theology was also rendered in liturgical objects and ecclesiastical architecture — particularly in altars, baptismal fonts, tabernacles, and carved keystones.

The marble altar shown above featuring the Vultus Trifrons is one of several known sculptural representations that depict the Holy Trinity through a shared head with three faces. Such carvings were often found in sacristies or monastic chapels where symbolic theology was taught through form rather than image. These expressions were not meant for broad public devotion, but rather for initiated contemplation, aligning with Neoplatonic aesthetics and the theological conviction that God’s unity and multiplicity could be contemplated in pure form — in the enduring solidity of stone or the flowing lines of carved wood.

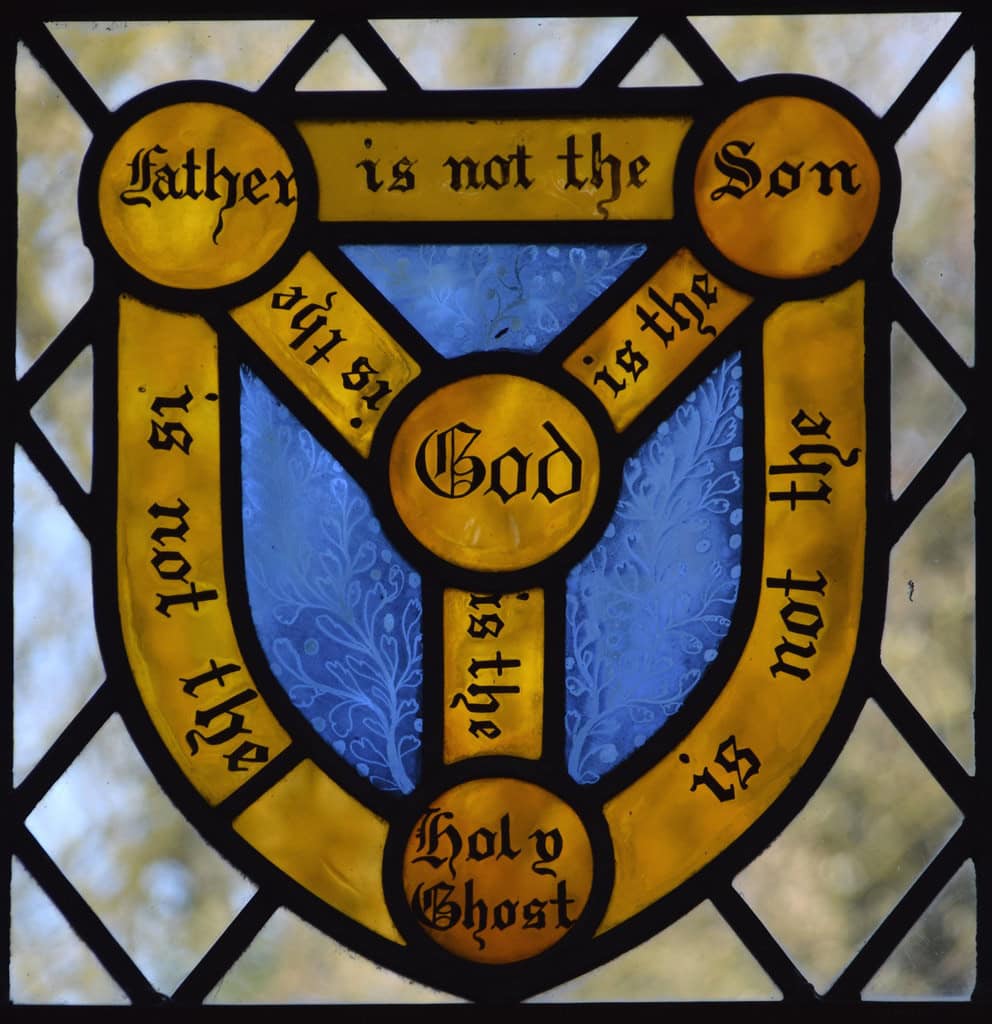

Scutum Fidei: The Latin Diagram That Saved Trinitarian Orthodoxy

While the three-faced image was banned, the Scutum Fidei or “Shield of the Faith” was retained as a visual catechism.

Prominently displayed on the chest of the divine figure in the painting, the diagram expresses the key truths of Trinitarian belief:

- Pater non est Filius (The Father is not the Son)

- Filius non est Spiritus Sanctus (The Son is not the Holy Spirit)

- Spiritus Sanctus non est Pater (The Holy Spirit is not the Father)

- Yet: Pater est Deus, Filius est Deus, Spiritus Sanctus est Deus

“The Scutum Fidei is theology rendered geometrically—logic and faith intertwined,”

— Dr. Rachel Fulton Brown, University of Chicago

Originating in the 12th century and popularised by Dominicans, the diagram avoided visual ambiguity and helped the faithful internalise Nicene orthodoxy during the Reformation era.

How Platonic and Scholastic Thought Shaped This Sacred Geometry

The triangle that frames the Trinity in this Netherlandish painting of the Three Faced God is far more than a decorative ornament—it is a theological and philosophical device, drawing deeply from the Platonic and Scholastic tradition. In both classical metaphysics and Christian theology, the triangle serves as a symbol of eternal harmony, indivisible unity, and ontological perfection.

The Triangle as the First Principle of Harmony

In Plato’s Timaeus, the triangle is described as the fundamental building block of the physical universe. All matter, according to Plato, is formed from triangles—specifically, from the right-angled and equilateral forms. These basic geometric shapes underlie the order of the cosmos and reflect the intelligibility of creation.

Later Neoplatonists, especially Plotinus and Proclus, developed this idea into a full cosmological system in which triads become the basic structure of all divine processions. The triadic form represents the dynamic interplay of:

- The One (τὸ ἓν): the unmanifest source,

- Nous (intellect): the first emanation,

- Psyche (soul): the world-soul or dynamic link to multiplicity.

This triadic pattern became a central schema through which early Christian thinkers would come to reimagine the Trinity, not as a logical puzzle, but as the archetype of divine and cosmic structure.

“All that is divine is constituted in threes,” writes Proclus (Elements of Theology, Prop. 101), a formula that strongly echoes through Christian metaphysical thought.

Augustine’s Psychological Trinity: Mind, Knowledge, Love

Among the Latin Fathers, Saint Augustine of Hippo was the first to systematise the Trinity in light of both scriptural revelation and Platonic metaphysics. In De Trinitate, Books IX–XV, Augustine develops a psychological analogy to reflect the image of God in the human soul.

According to Augustine:

- The mind (mens) exists and knows itself,

- Through knowledge (notitia), it becomes self-aware,

- And through love (amor), it delights in this knowledge.

These three faculties are distinct, yet inseparable—mutually indwelling (perichoresis), reflecting the divine unity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

“Behold, I who speak am mind; I speak something that is in my mind, and I love both the mind and its word. Three, yet one,”

— De Trinitate, XV.27.50

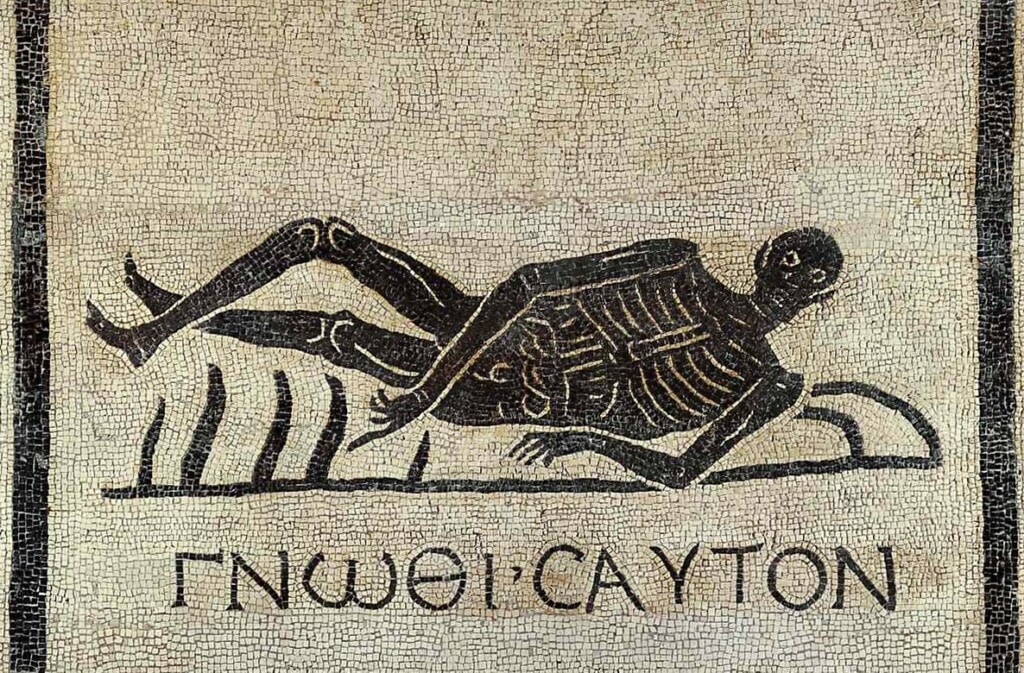

In this light, the triangle surrounding the Trinity in the painting can be read as symbolising the human soul made in the image of God, echoing the Platonic maxim Γνῶθι σεαυτόν gnōthi seauton (know thyself), not only as self-knowledge, but as a mirror of divine life.

Aquinas and the Logic of Relations in the Divine Nature

Where Augustine provided the metaphorical framework, Thomas Aquinas brought rigorous Aristotelian logic to Trinitarian theology. In the Summa Theologiae, particularly Questions 27–43 of Part I, Aquinas affirms that the divine persons are not distinguished by essence, will, or action, but solely by relations of origin:

- The Father is unbegotten,

- The Son is begotten (per modum generationis),

- The Holy Spirit proceeds (per modum spirationis) from both.

Yet all three are co-equal, consubstantial (homoousios), and inseparable in operation (opera Trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa).

This leads Aquinas to a paradox: a unity of three distinct hypostases that share one indivisible substance (una essentia). The triangle, with its three angles in one enclosed figure, provides a visual grammar for this metaphysical mystery. It offers what Aquinas calls a “likeness, not an equivalence” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 33, a.1).

Sacred Geometry as Visual Theology

In this theological and philosophical synthesis, the triangle becomes a sacred geometry—a contemplative form that encodes truths beyond verbal expression. For monks, cathedral architects, and theologians, such forms served as visual meditations, a way to engage the mystery through spatial harmony and intellectual ascent.

Cathedral rosettes, altar triptychs, and iconographic compositions often follow this triadic principle, rooted in the Neoplatonic belief that beauty reveals the divine. In art, the Trinity was not just dogma, but cosmic order revealed through proportion.

“The eye, the mind, and the soul are one in contemplation when faced with divine proportion,”

— Pseudo-Dionysius, Celestial Hierarchy, III.2

This painting, then, is not merely instructional—it is a visual “Summa Theologiae”, a theological diagram rendered with pigment, symbol, and line. It invites the viewer not just to believe, but to behold.

Visual Catechesis: Evangelists, Angels, and the Papal Tiara

Surrounding the central figure of the Trinity in this 17th-century Netherlandish composition are four iconic figures—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—each accompanied by a Gospel book and quill. These are not merely decorative elements, but central witnesses to the revelation of the divine mystery of the Trinity, affirming that this metaphysical doctrine is not speculative philosophy, but is drawn directly from Sacred Scripture, proclaimed in the liturgical and sacramental life of the Church.

In the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions, sacred art is never just illustration—it is visual theology. Rooted in Platonic and Neoplatonic metaphysics, these traditions uphold the idea that images can elevate the soul toward the invisible, and that symbol is a legitimate and even necessary vehicle for contemplating divine truth. This is in direct continuity with the theology of the Church Fathers, particularly those formed in the intellectual schools of Alexandria, Cappadocia, and the Latin West.

The Evangelists and the Eternal Gospel

Each of the Evangelists is not simply a historical figure but a metaphysical principle in traditional iconographic language. Associated with the four living creatures described in Ezekiel 1:10 and Revelation 4:7, they represent the fourfold manifestation of the Logos:

- Matthew, represented by the man or angel, symbolises Christ’s humanity and Incarnation.

- Mark, with the lion, expresses royal power and resurrection.

- Luke, as the ox, refers to priesthood and sacrifice.

- John, the eagle, symbolises the divine ascent and contemplation.

The Eastern Orthodox tradition especially preserves this iconographic tetramorph in liturgy and sacred space—often at the four corners of the dome or sanctuary—signifying that the Gospel penetrates all dimensions of time and space, just as the four winds surround the throne of God.

In Western sacred art, including this painting, their presence around the Trinity affirms that the mystery of una essentia, tres personae is revealed through scripture, and not invented by philosophical abstraction. In fact, it is the Gospel that invites the believer into the contemplation of the metaphysical depth of God.

The Papal Tiara and the Angelic Hosts: Sacred Order and Metaphysical Hierarchy

Below the Evangelists, flanked by adoring cherubim, rests the Triregnum, the papal tiara. This triple crown symbolises not merely jurisdictional power, but a metaphysical office: the Pope, like the bishop in Orthodox tradition, is the visible head of the Church precisely because Christ—the invisible Logos—is the head of the mystical body.

The three tiers of the tiara are often interpreted as symbolising:

- The Father of princes and kings (dominion over the created order),

- The Ruler of the world (governing the Church),

- The Vicar of Christ on earth (spiritual union with the Logos).

These three aspects reflect a Platonic triad of the soul—appetitive, rational, and contemplative faculties—and likewise echo the Dionysian celestial hierarchy (Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones), which structure the invisible Church. In Catholic and Orthodox metaphysics, the cosmos is not a random assembly of forms, but a divinely ordered chain of being (scala entis), where visible symbols reflect and participate in invisible realities.

In this painting, the cherubim lifting the tiara affirm that ecclesial authority is not political, but ontological. The bishop or pope is not simply a ruler, but a liturgical mediator, an icon of Christ who guards the mysteries and maintains doctrinal harmony with the Logos.

The Catholic and Orthodox Defence of Sacred Symbolism

Unlike the Protestant Reformers, who often interpreted such images as idolatrous or superstitious, both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches have preserved the original Platonic and Neoplatonic understanding of symbolic knowledge (symbolon) and sacramental vision.

For both traditions, truth is not exhausted by literalism. The divine cannot be reduced to propositional logic or textual minimalism. Instead, it must be approached through symbol, mystery, and liturgy—where the soul ascends by means of visible signs toward invisible realities.

“The visible is the garment of the invisible,” writes St. Maximus the Confessor, echoing Plato’s cave in Christian terms.

“In contemplating the outer form, the soul is invited into union with the archetype it reveals.”

This is why the Church always understood art as a sacred medium. The images were not idols but icons—windows into the eternal. The use of Evangelists, angels, and the Triregnum in this painting forms a cosmic liturgy in paint, teaching without speech, and affirming that the Church is not merely institutional but mystical, metaphysical, and sacramental.

Parallel Vision: Orthodox Visual Theology and the Metaphysics of the Icon

While the Western tradition of sacred art embraced scholastic clarity and hierarchical symbolism in response to the Reformation, the Eastern Orthodox Church retained a complementary path: one rooted in hesychasm, mystical theology, and the profound metaphysical framework of iconography.

In Orthodox tradition, the icon is not merely a devotional image; it is a sacrament of presence, a visible hypostasis of an invisible reality, grounded in the Incarnation and in the unbroken Platonic and Neoplatonic worldview of the Church Fathers.

“An icon is not art, but vision,” writes Leonid Ouspensky, one of the greatest modern Orthodox theologians of the icon. “It does not depict the natural world, but the transfigured one.”

The Icon as Symbol of Ontological Participation

The Orthodox worldview affirms that form participates in essence—a principle at the heart of both Platonic philosophy and Eastern patristic theology. The icon is, therefore, not mimetic but anagogic—leading the viewer from the visible to the intelligible, from the sensible image to the eternal archetype (archetypos).

This metaphysical understanding is rooted in Dionysius the Areopagite, who taught that all of creation is a hierophany—a manifestation of divine order. The icon is a particular kind of hierophany: a visual manifestation of divine energies (energeiai) made accessible through sanctified matter, line, and colour.

Hence, just as the Scutum Fidei in Western art expresses theological clarity, the Orthodox icon expresses mystical presence. Each has the same purpose: to draw the soul toward the Triune God through contemplation and reverence.

The Evangelists in the Dome: Liturgical Space and Cosmological Order

In Orthodox churches, the Evangelists are not usually arranged at the periphery of theological diagrams but are placed within the dome or apse, forming a visual circle around the Pantokrator (Christ the Almighty). Their placement symbolises the four directions of the cosmos and the universality of the Gospel. They are also understood to reflect the four logoi—divine principles within creation, which echo the mind of the Logos.

The tetramorph remains active in Orthodox iconography but is never rendered as pure allegory. Instead, it operates anagogically—inviting the viewer to behold Christ through the eyes of the Evangelists, each of whom manifests a unique aspect of divine revelation. This is deeply consonant with the Neoplatonic principle that multiplicity reflects the richness of the One, without breaking unity.

Hierarchy and Divine Order: The Angelic Hosts

Orthodox iconography maintains a cosmic order of beings, derived directly from Pseudo-Dionysius’ Celestial Hierarchy, which continues Platonic metaphysics in a Christian key. The nine orders of angels—Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels—are not depicted arbitrarily but positioned with liturgical precision in the structure of the sanctuary.

This visual theology forms a sacred hierarchical cosmos where all beings—human and angelic—are oriented toward the Uncreated Light. This theology of light (seen, for instance, in the icon of the Transfiguration) expresses the divine energies radiating from the Trinity, experienced in the liturgy and perceived through the nous (the intellect of the heart).

Icons, unlike Western naturalistic paintings, are intentionally non-perspectival. The perspective is reversed, placing the viewer inside the sacred space, where earthly time opens into eternity, and space becomes symbolic.

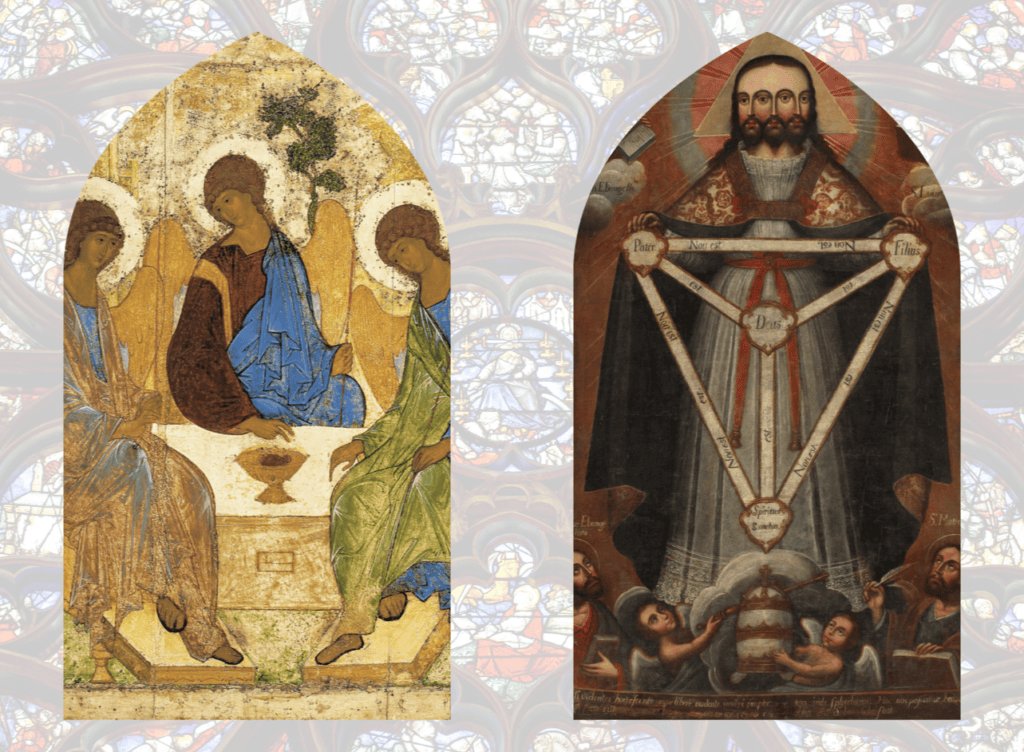

The Holy Trinity in Orthodox Iconography

While the Vultus Trifrons is foreign to Eastern iconography, the Orthodox tradition developed its own theological expression of the Trinity—most famously in Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Hospitality of Abraham, which depicts the three angels who visited Abraham at Mamre (Genesis 18).

This icon does not attempt to “explain” the Trinity, but rather to invite contemplation. The angels sit in perfect circular harmony, with gestures that echo the inner life of divine love. Their identical faces and subtle postures reflect the eternal communion of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, in keeping with Orthodox apophatic theology: God is not grasped through definition, but encountered in silence, stillness, and image.

“The icon of the Trinity is not a representation of what God is, but of how God invites,”

— Pavel Florensky, The Iconostasis

The Shared Vision: Unity Beyond Form

Despite stylistic and theological differences, both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox visual traditions uphold a shared metaphysical vision:

- That truth is revealed through symbol,

- That form participates in the eternal,

- And that the human soul ascends to God through contemplation of beauty, harmony, and mystery.

Where the West speaks in the language of dogma and sacred geometry, and the East in the language of silence and icon, both are drawing from the same Platonic-Christian inheritance—where the visible world reflects the invisible order of divine being.

Together, they testify to a profound truth:

“God is not the object of our sight, but the light by which we see.”

— St. Gregory of Nazianzus

Visual Theology Across Traditions: Comparing the Eastern and Western Trinity

Combined image above: Left – (Orthodox) | Right – (Catholic)

| Aspect | Eastern Orthodox (Rublev) | Western Catholic (Vultus Trifrons) |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Imagery | Genesis 18 – The three angels at Mamre | Direct theological representation of the Trinity |

| Approach | Mystical, contemplative, apophatic theology | Didactic, scholastic, metaphysical theology |

| Faces or Figures | Three identical angels with unique gestures | Three conjoined faces on a single head |

| Theological Emphasis | Divine communion, Trinitarian harmony, hospitality | Unity of essence, distinction of persons, Trinitarian ontology |

| Artistic Style | Inverse perspective, spiritualised form | Geometric structure, scholastic clarity, naturalism |

| Purpose | To lead the soul into silence and divine mystery | To instruct the faithful and affirm doctrinal orthodoxy |

Conclusion: Why the Banned Image Still Matters Today

Though officially outlawed, the image of the Three Faced God—the Vultus Trifrons—remains one of the most haunting and thought-provoking artefacts in the history of Christian visual theology. Far from being a theological error, it is a mirror reflecting a time when mystery and doctrine were not enemies, but collaborators. It belongs to an era when faith sought the help of the senses, and when artists, theologians, and mystics worked side by side to render the invisible God in visible form—not to limit Him, but to invite contemplation.

This image was born not out of heresy, but out of fidelity—an attempt to capture in a single figure the divine paradox: one God, yet three Persons; one substance, yet three hypostases. It was the visual equivalent of a metaphysical proposition, a creed carved in flesh, paint, or stone, bridging Neoplatonic metaphysics and Christian dogma. And while the ecclesiastical guardians of doctrine eventually deemed such imagery too easily misunderstood, its existence reminds us of the creative daring and intellectual seriousness with which the ancients approached the sacred.

“Art allows the soul to ponder what reason alone cannot resolve.”

— Cardinal Federico Borromeo, 1625

In our own time—so often divided between iconoclasm and sentimentality—this forgotten icon challenges us to recover a sacramental imagination, where forms are not decorative but instructive, and where images do not entertain, but initiate. It invites us back to a worldview in which symbol is truth made visible, and geometry, light, and line can lead the soul toward God.

The banned image of the Trinity is not a theological relic, but a living question: Can mystery still be shown? Can doctrine still inspire awe? Can the soul still be moved not just by what it understands, but by what it intuits?

In the end, the image whispers what the Church Fathers proclaimed, what the mystics intuited, and what the faithful still confess:

Tres personae. Una essentia. Deus unus.

Three persons. One essence. One God.

References and Further Reading

- Augustine of Hippo, De Trinitate. Trans. Edmund Hill. New City Press, 1991.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Part I, Questions 27–43. Latin-English Edition.

- Mâle, Émile. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages. Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Spieser, Jean-Michel. The Representation of the Divine in Christian Art. Brill, 2004.

- Hamburger, Jeffrey. The Visual and the Visionary: Art and Female Spirituality in Late Medieval Germany. Zone Books, 1998.

- Gurewich, Vladimir. “The Three-Faced Trinity.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 17, No. 1/2 (1954), pp. 170–178.

- O’Malley, John W. Trent and All That: Renaming Catholicism in the Early Modern Era. Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Fulton Brown, Rachel. From Judgement to Passion: Devotion to Christ and the Virgin Mary, 800–1200. Columbia University Press, 2002.

- Lavin, Irving. “The Dogma of the Trinity in Art.” Art Bulletin, Vol. 60, No. 1 (1978), pp. 20–38.