Warrior Queen Cartimandua: Discovery of Her Tomb? A Groundbreaking Iron Age Find

In a development that has electrified historians and archaeologists worldwide, archaeologists from Durham University recently unveiled an extraordinary Iron Age hoard near Melsonby, North Yorkshire. This cache, believed to be 2,000 years old, is not only one of the largest and most significant Iron Age finds in the United Kingdom, but it may also be tied to one of Britain’s most enigmatic figures—Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes.

Who Was Queen Cartimandua?

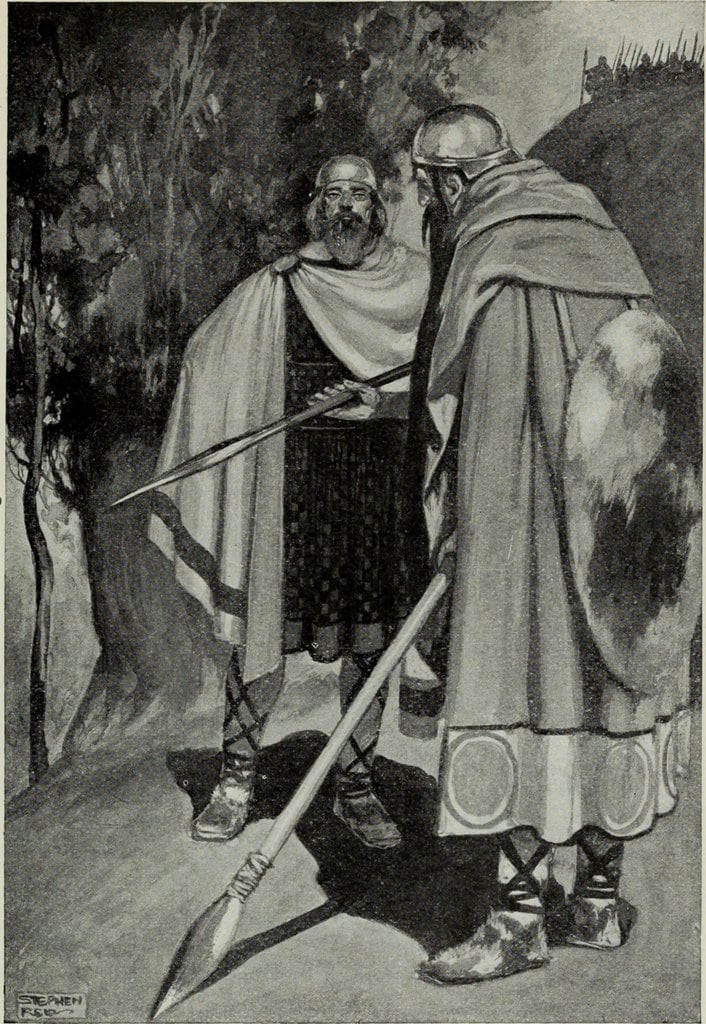

Warrior Queen Cartimandua reigned over the Brigantes, a dominant Iron Age tribe in northern Britain, during the Roman conquest of the first century AD. She carved out a distinctive political niche by allying herself with Roman forces—a rarity among indigenous rulers of her time. The Roman historian Tacitus provides us with crucial details of her reign, including the episode when Cartimandua captured the British resistance leader Caratacus in AD 51 and handed him over to the Romans. This act solidified her regional power and entrenched her standing with Rome.

Yet, Cartimandua’s story was far from simple. Her decisions ignited internal tensions within the Brigantes, especially with her estranged husband, Venutius, who repeatedly challenged her pro-Roman stance. These domestic and political upheavals underscore Cartimandua’s unwavering resolve to maintain authority amidst relentless opposition, a theme explored in depth in the Oxford Classical Dictionary and the Journal of Roman Studies.

Historic Breakthrough: The Recent Discovery in Melsonby

The hoard found near Melsonby comprises a dazzling array of funerary objects, including:

- Cauldrons and bowls

- Intricately crafted brooches, bracelets, and other jewellery

- Weapons from the Iron Age

- Parts of entire chariots, including horse harnesses and vehicle parts

Dr. Sophia Adams of the British Museum described it as “the largest single deposit of horse harness and vehicle parts excavated in Britain,” emphasising the extraordinary significance of this discovery.

Meanwhile, Professor Tom Moore, head of archaeology at Durham University, labelled it “exceptional for Britain and probably even Europe,” pointing out how it redefines our understanding of the wealth and power networks in northern Britain during the Iron Age.

Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications: The Power Center?

Adding to the intrigue is the site’s proximity to the Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications. This expansive archaeological complex is widely believed to be a capital or strategic stronghold for either Cartimandua or her rival Venutius. Early excavations spearheaded by Sir Mortimer Wheeler and later by researchers from Durham University demonstrated that Stanwick was likely a significant political and economic hub. The fortifications’ size and strategic design reflect the power dynamics of the era, lending credence to the idea that the newly discovered hoard—possibly a royal burial site—could be related to a figure of immense status and influence.

Could This Be Warrior Queen Cartimandua’s Final Resting Place?

The claim that this might be Queen Cartimandua’s tomb naturally sparks tremendous excitement among scholars and the public. Experts exercise caution, however, emphasising that comprehensive carbon dating, DNA analyses, and meticulous studies of any human remains are needed for definitive proof. Still, the sheer opulence of the items—ranging from luxury funerary goods to formidable weapons—implies that whoever was buried at this site possessed considerable prestige, potentially royalty.

For those familiar with Cartimandua’s complex legacy, this discovery offers a window into a pivotal historical chapter. The Brigantian queen walked a political tightrope, forging alliances with the might of Rome while grappling with internal dissent from factions led by Venutius. This alliance-based governance strategy has been widely studied and detailed in publications such as the Journal of Roman Studies.

Historical Context

Warrior Queen Cartimandua’s reign was not simply a footnote in Roman or British history; it represented a key turning point in how local rulers negotiated power with a vast imperial force. Tacitus’s records, along with modern archaeological and historical scholarship, suggest Cartimandua carefully balanced alliances to protect Brigantian interests—at least for a time. The newly discovered artefacts near Melsonby might further illuminate the economic, military, and cultural dimensions of that era.

Moreover, Stanwick’s elaborate defences, artefacts, and now this latest Melsonby hoard could reshape our understanding of Iron Age Britain. Each discovery brings us closer to understanding how Cartimandua’s Brigantes lived, governed, and interacted with continental Europe.

Isurium Brigantum And The Cult of Brigantia

The Brigantes were one of the most powerful and extensive Celtic tribes in Roman Britain, occupying a vast territory in the north of England, from the Irish Sea to the North Sea and stretching from the River Humber up toward what later became Hadrian’s Wall. Their political prominence is attested by Roman sources such as the geographer Ptolemy, who identifies Isurium Brigantum (modern-day Aldborough) as their capital.

Tacitus provides the most detailed account of their internal affairs, particularly during the reign of their queen, Cartimandua. A shrewd political operator, Cartimandua allied herself with the Romans and captured the rebel leader Caratacus, handing him over to Emperor Claudius. This act secured Roman favour but led to civil unrest and rebellion within her tribe, notably from her ex-husband Venutius. Tacitus’ Histories and Annals portray her rule as a volatile chapter in the Romanization of Britain, where native aristocracies attempted to balance independence with imperial diplomacy.

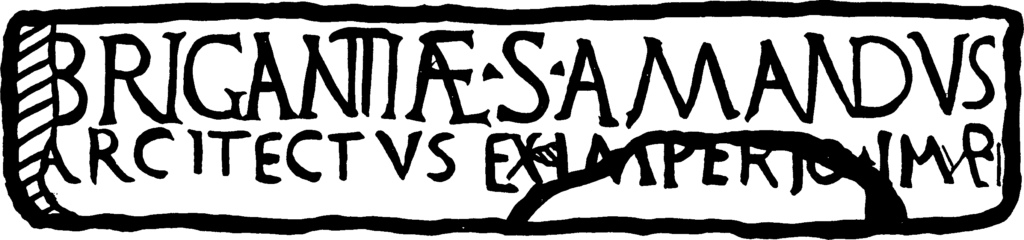

The name “Brigantes” is believed to derive from the Proto-Celtic root brigantī, meaning “high” or “exalted,” a term that evokes both physical elevation and noble status. This root also underlies the name of the goddess Brigantia, who was likely the tutelary deity of the tribe. The cult of Brigantia originated in Gaul (modern-day France), where the root brig- is found in numerous place names and theonyms, and later spread to Britain with migrating or culturally linked Celtic groups. As linguist Xavier Delamarre notes, Brigantia shares clear etymological ties with Gallic deities such as Bricta, suggesting a wider continental Celtic tradition. In Britain, Brigantia’s worship was especially prominent in the north and appears to have maintained its distinctiveness even under Roman occupation.

Several inscriptions dedicated to her survive, often syncretizing her with Roman goddesses such as Minerva and Victoria. As Anne Ross affirms in Pagan Celtic Britain, Brigantia was “one of the few indigenous goddesses in Britain who maintained a strong, identifiable character even under Roman rule.”

Over time, Brigantia’s image evolved within Roman Britain, eventually contributing to the development of the symbolic figure of Britannia. As Roman rule sought to incorporate native traditions into its imperial cult, Brigantia’s qualities of protection, wisdom, and martial strength became associated with Rome’s own divine personifications. The figure of Britannia, first appearing on Roman coinage in the second century AD, reflects this fusion of indigenous and imperial imagery. As Miranda Green explains in The Gods of the Celts, the process illustrates how:

“local cults could be absorbed and transformed into wider imperial symbols.”

Thus, Brigantia was not only the spiritual emblem of the Brigantes but also a foundational figure in the evolving identity of Roman and post-Roman Britain, bridging native Celtic belief with imperial ideology.

Was Warrior Queen Cartimandua Linked to Boudica?

Boudica (also spelt Boudicca or Boadicea) was the famed queen of the Iceni tribe in Eastern Britain who led a major uprising against Roman rule around AD 60–61. While Cartimandua and Boudica were contemporaries, their paths diverged significantly:

1. Allegiances:

- Cartimandua’s pro-Roman stance helped her maintain power and secure military support.

- Boudica led a full-scale rebellion against Rome, uniting other tribes to challenge imperial dominance.

2. Geographical Separation:

- Cartimandua ruled over the Brigantes in northern Britain.

- Boudica and the Iceni were based in the eastern region (modern-day East Anglia).

3. Limited Historical Evidence:

- Despite speculation, there is no conclusive evidence that Cartimandua and Boudica ever formed an alliance or met in battle.

- Tacitus and other ancient sources do not document any direct political or military interactions between these two queens.

4. Possible Indirect Influence:

- Given their conflicting stances toward Rome, it is possible that tribes under Cartimandua’s influence chose not to join Boudica’s uprising.

- Cartimandua’s cooperation with Rome likely reinforced imperial power in the north, making it harder for Boudica’s rebellion to spread beyond central and southeastern Britain.

In short, Cartimandua’s decision to side with Rome stood in stark contrast to Boudica’s violent revolt. While both were powerful female rulers of Celtic tribes, their divergent strategies highlight the complexity of indigenous responses to Roman occupation.

Additional Insights on Warrior Queen Cartimandua

Brigantian politics

Archaeological finds of ritual sites near Stanwick suggest that religious leaders may have held sway in Brigantian politics. Evidence at Stanwick points to a variety of ceremonial structures and offerings that hint at an influential religious class. These findings—ranging from altars or enclosures to possible ritual depositions of metalwork—suggest that spiritual practices were integral to community identity. Such dedicated ritual spaces, carefully separated from domestic areas, emphasise how sacred ceremonies could have underpinned Brigantian social bonds, reinforcing unity and collective purpose.

Despite the limited documentary evidence, the material record implies that local religious officials or revered individuals exercised significant influence. Their roles likely went beyond mere ceremonial duties, guiding important decisions, including alliances, distribution of resources, and the adjudication of internal disputes. In societies without extensive written traditions, ritual authority often merged with political power, allowing religious leaders to shape the way communities interacted with neighbouring polities or even distant powers like Rome.

It is important to note that while these religious figures wielded power, they did so within the distinct cultural context of Iron Age Britain. The Brigantes would have developed their own indigenous practices—adaptive, evolving, and reflective of regional values—rather than conforming to a single standardised belief system. This regional uniqueness highlights the complexity of Iron Age religious life: each group, including the Brigantes, could have established its own forms of political-religious leadership, shaped by geography, local tradition, and ongoing interactions with the Roman world.

- Securing a Roman Alliance: By handing over the British resistance leader Caratacus to the Romans in AD 51, Cartimandua showcased impressive diplomatic skills. This act strengthened her reputation as a dependable Roman ally, ensuring ongoing military protection and reinforcing her status at the helm of the Brigantes.

- Rivalry with Venutius: Cartimandua’s estranged husband, Venutius, mounted multiple rebellions to counter her pro-Roman policy. Their tumultuous relationship exposed deep internal fault lines within the Brigantes, ultimately contributing to a loss of unity and power that paved the way for further Roman influence in northern Britain.

Cultural and Ritual Practices in Northern Britain

- Ritual Deposits: While the Brigantes regularly offered weapons, jewellery, and chariot parts in ceremonial contexts, such ritual depositions were not necessarily linked to Druidic worship, as some popular accounts have suggested. According to expert French historians such as Jean-Louis Brunaux, Druids were primarily active in Gaul—and potentially originated from communities of Greek settlers in southern Gaul—rather than in Britain.

- Local Religious Customs: Northern British tribes, including the Brigantes, practised their own indigenous religious and cultural traditions, which may have involved local priesthoods and communal rites. However, the idea of Druidic presence in Britain is contested by experts such as Jean-Louis Brunaux, who argue that Druids were limited to the Gallic territories (Gaul/France).

Placing Cartimandua’s diplomatic strategies, ritual practices, and religious context in a broader perspective that acknowledges the view that Druids may have been confined to Gaul provides us with a nuanced account of her era. Therefore, it highlights regional variations in belief systems and underscores the distinctive historical circumstances faced by the Brigantes during the Roman conquest.

The Greek–Gallic Connection and the Philosophical Roots of Druidism

The expert French historian Jean-Louis Brunaux underscores the pivotal role played by the Greek colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille) in shaping Gallic (Gaulish) intellectual life. Through this Greek outpost in southern Gaul, the Gallic elite maintained continuous contact with the Hellenic world, creating fertile ground for cultural exchange. This interaction may account for the apparent philosophical parallels between Druidism and Greek thought. For more about the Druids, see our Special Edition Templarkey magazine on the Druids.

Pythagorean Influences on Druidic Teachings

From the 2nd Century AD, key authors and observers repeatedly drew comparisons between Druids and Pythagoreans, noting shared beliefs and practices:

1. Transmigration of Souls (Reincarnation): Both Druids and Pythagoreans taught the cycle of rebirth, emphasising the soul’s immortality.

2. Oral Tradition: Druids, like Pythagoreans, refused to commit sacred teachings to writing, preserving their doctrines through memorisation and oral instruction.

3. Focus on Abstract Knowledge: They both studied astronomy, mathematics, and metaphysics—branches of learning often associated with advanced Greek philosophy.

Saint Hippolyte (2nd Century AD) remarked, “The Druids among the Celts applied themselves with particular zeal to the philosophy of Pythagoras.”

Meanwhile, the 4th-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus observed, “The Druids formed themselves into communities whose statutes were the work of Pythagoras, and their minds were always focused on the most abstract and difficult questions of metaphysics.”

Such direct statements reveal not only superficial resemblances but also a deep philosophical kinship between Greek intellectual traditions and Druidic teachings in Gaul.

The Decline of Druids Under Roman Rule

With the Roman conquest of Gaul, the last Druids either adapted to new power structures or faded into obscurity:

- Integration into Roman Society: Gallo-Roman aristocrats of Druidic background often assimilated into Roman governance or took on monastic roles under Christian influence.

- Preservation of Intellectual Lineages: Certain families in Gaul continued to embrace elements of Druidic knowledge, albeit in discreet, syncretic forms. For instance, the Ausonius family, known to use names like Dryadia and Arborius, hints at their sustained link with ancient Druidic traditions.

As Brunaux notes “The old aristocratic Gallo-Roman families kept alive traces of their intellectual traditions, but they were entirely integrated into the new Roman world.”

No Historical Evidence for Druids in Britain

While Druids were present in southern Gaul due to robust Greek–Gallic interaction and philosophical exchange, there is no conclusive historical evidence pointing to a similar Druidic tradition in Britain. The lack of archaeological data and the absence of direct references in ancient sources strongly suggest that any priestly caste present in Britain operated independently of the Greek-influenced Druidic schools of Gaul.

Rethinking “Celtic” Identity: Were Celts Only in France?

A commonly held view in modern scholarship is that the “Celts” once spanned much of Western Europe, including regions of Britain and Ireland. However, some researchers and historians argue a more restrictive definition: that genuine Celtic culture existed solely in ancient Gaul, located in modern-day France, and did not extend into the British Isles. From this standpoint:

- Gaul as the Celtic Heartland:

- Ancient Greek and Roman writers frequently referred to the peoples of Gaul as “Celts.” The term was not systematically applied to tribes in Britain, suggesting an ancient cultural and geographical

- Greek contacts through Massalia (Marseille) and Roman reports typically emphasise Gaul (rather than Britain) as the cradle of Celtic language and priestly traditions—including the Druids.

1. Britain’s Distinct Indigenous Tribes:

- Groups such as the Brigantes, ruled by Cartimandua, are viewed by these scholars as indigenous Iron Age societies, rather than offshoots of a French-based Celtic network.

- Their religious practices, political structures, and social organisation may have been rooted in locally developed traditions, not in Gallic “Celtic” culture.

2. Druidism Confined to Gaul:

- In line with the argument that “Celts” were Gaul-based, Druidism is similarly believed to have flourished only among Gallic aristocrats and intellectual circles.

- The lack of archaeological evidence or direct testimony for Druids in Britain supports this Gaul-only perspective, undermining the once-popular notion of British Druids at sites like Anglesey or in Northern England.

Cartimandua in an Indigenous Context

Placing Cartimandua outside of a Celtic framework means viewing her reign in northern Britain as an independent Iron Age monarchy rather than a direct offshoot of Gaulish cultural or religious traditions:

- Pro-Roman Diplomacy: Cartimandua’s partnership with Rome (marked most famously by her handover of Caratacus) was a pragmatic choice rooted in local power struggles, not necessarily reflective of any pan-Celtic sentiment.

- Distinct Ritual Practices: Although rich funerary deposits near Melsonby echo customs seen elsewhere in Iron Age Europe, they may represent regional rites—unique to the Brigantes—rather than a “Celtic” or Druidic ceremony.

Historical Debate and Continuing Research

Some experts continue to advocate for a broader Celtic identity encompassing Britain and Ireland, citing linguistic and material cultural evidence. Yet, others point to:

- Limited Direct Literary References: Greek and Roman authors generally refer to mainland Gaul when discussing “Celts,” rarely using the label for inhabitants of Britain.

- Archaeological Distinctions: Finds in Britain—such as Stanwick or Melsonby—show enough regional divergence that they need not be pigeonholed into a larger “Celtic” continuum.

Ultimately, as modern historians now offer updated research of an exclusively Gaul-based Celtic culture, not a wider “Celtic world” of a France-focused Celtic civilisation, they highlight how different definitions of culture, language, and identity can dramatically reshape our understanding of Iron Age peoples—both on the European continent and in the British Isles.

Cartimandua’s Lasting Influence

- Female Authority in Iron Age Britain: Cartimandua’s decision-making and ability to command loyalty among factions within her tribe highlight the impact female leaders could have in societies. Her alignment with Rome proved that forging external alliances was sometimes more pragmatic than outright rebellion, especially when power needed to be shored up against internal challengers.

- Northern Britain’s Role Under Rome: Cartimandua’s cooperation smoothed Rome’s expansion into northern Britain by reducing local resistance. After Cartimandua’s reign ended—due in part to Venutius’s insurrections—the Brigantes experienced increasing Roman intervention, which shaped subsequent regional politics and cultural transitions.

Concluding Thoughts and Implications for the Future

This Melsonby discovery is more than just a treasure trove of Iron Age artefacts; it could unlock vital insights into royal funerary customs, regional power structures, and cross-cultural ties in ancient Britain. The curiosity and caution exhibited by leading archaeologists underline the need for long-term studies, peer-reviewed research, and collaborative excavations. If confirmed to be Cartimandua’s tomb, this site may become one of the most iconic archaeological landmarks in Europe.

Whether or not these remarkable finds near Melsonby ultimately prove to be the Warrior Queen Cartimandua’s final resting place, the 2,000-year-old hoard has already taken its place among the most significant in British history. It underlines the potential for Iron Age discoveries to challenge and refine our understanding of ancient Britain’s political landscape, cultural complexity, and evolving relationships with Rome. As more data emerges from ongoing excavations and analyses, historians and enthusiasts alike will be waiting with bated breath for what could be one of the most transformative revelations in British archaeology.

References and Further Reading

- Durham University Press Release

- The Guardian: Iron Age Hoard Discovery

- The Independent: Expert Opinions

- Oxford Classical Dictionary: Cartimandua

- Journal of Roman Studies: Queen Cartimandua

- Historic England: Official Statements on Iron Age Finds