Who Was Saint Valentine? The True Story Behind Valentine’s Day

Valentine’s Day (February 14th) arrives like clockwork, dressed in its familiar costume: roses that wilt with theatrical speed, cards that promise eternity in the lifespan of a fortnight, and a soft commerce in affection that makes even the most sceptical among us glance twice at a shop window. It is all so polished, so settled, that we are tempted to believe it must have been ever thus—love, red ink, and a saint smiling benignly from the calendar.

History, however, is rarely so obliging.

Ask the apparently simple question—who was St Valentine?—and the ground shifts under your feet. The figure now marketed as the patron saint of lovers is not a single, clean silhouette but a puzzle of overlapping lives and pious memory. The Roman Martyrology, the Church’s formal catalogue of saints, lists two Valentines from Italy, both commemorated on 14 February: one a priest associated with Rome and the Via Flaminia, the other a bishop of Terni (ancient Interamna), in Umbria. Both are remembered as martyrs. Both are said to have performed healing miracles. Both are said to have been executed by beheading within a short distance of each other, in the turbulent late third century.

This is the first surprise. The second is more unsettling for modern sentiment: in the earliest layers of the tradition, there is little sign that Valentine’s feast had anything to do with romance as we now understand it. The familiar story—secret weddings, forbidden lovers, and hearts sealed with vows—belongs largely to later legend and cultural invention. The link between St Valentine’s Day and romantic love, as modern scholarship increasingly suggests, was forged not in the catacombs of imperial Rome but in the imaginative workshop of medieval poetry and the slow evolution of social custom.

If Valentine’s Day has a patron, it may be less a single saint than the strange partnership of martyrdom, memory, and the human need to turn dates into meaning.

Framed as a question with historically grounded answers, Who Was Saint Valentine? The True Story Behind Valentine’s Day goes beyond a simple explanation to examine how meaning, martyrdom, and memory function within the Christian tradition.

The Problem with “Saint Valentine”: One Name, Several Martyrs

The difficulty with St Valentine begins where historians most like to begin: with names. “Valentinus” was not a rare oddity in the late Roman world; it was a plausible, respectable name, carried by more than one Christian whose life ended in the same grim currency—public execution, remembered by the faithful, recorded with varying degrees of precision, and then retold until a life becomes a pattern.

Early Christian martyr traditions were never compiled as modern biographies. They were, first and foremost, acts of remembrance: local communities recalling “their” holy dead, gathering at graves, keeping feast days, and passing on stories that served devotion as much as documentation. Over time, these memories acquired familiar motifs—healing miracles, confrontations with authority, imprisonment, steadfast confession, and a decisive death. Such motifs are not necessarily false; they are simply the narrative grammar of sanctity in an age when the Church was learning how to remember itself.

This is how overlap happens. A martyr’s story is told in one city, then retold in another. A shrine draws pilgrims, a relic is translated, a name is copied, a detail shifts. Two communities may cherish the same figure under slightly different descriptions—or cherish different figures whose stories gradually begin to resemble one another. Later writers, confronted with parallel traditions, often try to harmonise them: not out of deceit, but out of an instinct for coherence. The result can be a saint with a doubled biography, or a pair of saints with a shared silhouette.

Here, the key point is straightforward and stubborn: the Roman Martyrology lists two Valentines in Italy, and both are commemorated on 14 February. One is presented as a priest linked to Rome; the other as a bishop associated with Terni. From this single fact, the wider complication follows. Are we dealing with two martyrs whose stories converged, or one martyr remembered two ways—Rome and Terni each preserving a version of the same witness?

In brief: there may have been two Valentines—or one martyr remembered two ways.

What the Roman Martyrology Actually Says (and Why It Matters)

If this story is going to be more than a scented fog of legends, it needs a fixed point. The Roman Martyrology is one of the few places where the Church’s memory becomes textual and therefore checkable. But it must be read for what it is.

A martyrology is, in plain terms, an official register of martyrs (and, in time, saints more broadly): a liturgical record arranged by day, intended for commemoration, not for modern-style biography. It is closer to a calendar with terse identifications than to a historical dossier with sources, motives, and corroborating witnesses.

That distinction is not pedantry; it is the difference between evidence and embroidery. The Martyrology can tell us who was commemorated and when—and sometimes where tradition locates their death or burial. What it cannot reliably supply, by its nature, is the full narrative texture later generations often demand.

Read with that restraint, the Martyrology is still crucial for Valentine. In a Vatican summary of the Martyrology’s entry for 14 February, we find the core complication stated baldly: it “lists not one, but two Valentines” for that date. One is Valentine, priest and martyr, linked with the Via Flaminia in Rome and death by decapitation under Emperor Claudius II Gothicus; the other is Valentine associated with Terni, described as beaten, imprisoned, and then secretly taken out and beheaded on the orders of Placidus, prefect of Rome.

So what does this mean historically? At minimum, it anchors the article in something real: 14 February is a day of commemoration for “Valentine” in an official liturgical book, and the tradition had, by the time of the Martyrology’s received form, settled into two closely related commemorative notices.

What it does not mean is that every vivid detail in later retellings is automatically historical. The Martyrology’s strength is also its limitation: it is evidence of veneration and remembrance, not a guarantee of precise reconstruction. Treat it as commemoration first, and you gain something more valuable than romance: a disciplined way to handle uncertainty without making the reader feel lost.

Valentine the Priest of Rome: Miracles, the Via Flaminia, and a Beheading

The first Valentine in the Martyrology tradition is not introduced as a matchmaker. He appears as something both simpler and more disturbing: a priest and martyr, remembered at a location that was once a main artery of Roman power.

The Vatican summary of the entry places him “on the Via Flaminia in Rome”, calling him priest and martyr, associating him with healing miracles, and stating that he was killed by decapitation under Claudius Gothicus in 269-270 A.D.

The geography matters because it strips away the greeting-card haze. The Via Flaminia was not a poetic lane; it was one of Rome’s great roads, driving north towards the Adriatic and binding the city to the wider peninsula. To be executed there, it was to be killed in public, aligned with the state’s infrastructure—the power making a lesson out of a body.

Beyond that, the secure facts thin out quickly. Later legend embroidered this sparse outline with stories of clandestine marriage ceremonies (including couples that allegedly secretly married) and Valentine’s subsequent house arrest, but these details sit in the hagiographical afterlife rather than the earliest, securely attested record.

The Martyrology notice (as mediated in the Vatican summary) gives a sketch: name, status, place, manner of death, and a nod towards miracles. It does not give the modern reader what modern readers crave: a verifiable chain of events, reliable witnesses, documentary corroboration. This is why later stories—imperial conversations, named households, dramatic conversions—must be handled as later hagiographical development unless independently supported. The Martyrology is a starting point, not a court transcript.

What, then, should the reader carry forward at this stage?

Valentine of Rome, as preserved in liturgical memory, is a figure of martyrdom before romance: a cleric killed for faith, remembered at a Roman road whose very stones once spoke the language of empire. Everything else—however beloved—belongs to the next layer of the tradition, and must earn its historical status rather than assume it.

Medieval/late antique Hagiographical Tradition

What enters the tradition next belongs squarely to the medieval imagination rather than the secure ground of the Martyrology—but it is too influential to ignore. In one widely circulated legend, Valentine appears as a Roman priest named Valentinus, arrested during the reign of Claudius Gothicus and placed in the custody of an aristocrat called Asterius. The mistake, as the story tells it, was allowing the prisoner to speak.

Valentinus, unshackled in tongue if not in body, preached at length about Christ as light breaking into pagan darkness—salvation articulated not as an abstraction, but as a concrete escape from blindness, error, and shadow. Asterius, sceptical but intrigued, proposed a test rather than a rebuke. If Valentinus could restore sight to his blind foster daughter, the household would convert.

The priest agreed. He laid his hands over the girl’s eyes and prayed: “Lord Jesus Christ, enlighten your handmaid, for you are God, the true light.” According to the legend, the cure was immediate. The child could see. Asterius and his family received baptism.

It is at this point that the narrative tightens into the familiar martyr pattern. News reached the emperor. The conversions were intolerable. Executions followed. In some versions, the entire household was condemned; in others, the penalty fell squarely on Valentinus alone. What remains consistent is the ending: Valentinus was beheaded, and a pious Christian woman recovered his body and buried it along the Via Flaminia, the very road that once carried Roman authority northward out of the city. A chapel later rose over the grave. Memory solidified around stone.

Historians do not treat this account as courtroom evidence. Its value lies elsewhere. It dramatises, in human terms, the themes already visible in the official tradition: healing, conversion, defiance of authority, and death understood as witness. It also explains—far better than modern romance myths—why Valentine’s name would persist in Christian memory long before it acquired any association with love.

Valentine of Terni: A Bishop, a Prefect, and a Second Decapitation

Interamna (Terni) and the local cult

The second Valentine in the tradition is anchored not in Rome’s arterial road system but in a provincial city with a long memory: Terni, ancient Interamna, in Umbria. The Roman Martyrology tradition, as summarised in Vatican sources, preserves him specifically as the Valentine “in Terni”.

This matters because saints are not only remembered; they are kept. Late antique Christianity was intensely local in its devotional geography. Communities gathered at tombs, guarded relics, told stories that linked holiness to familiar streets and civic landmarks, and gradually wove a martyr into the identity of a place. In that world, the saint’s shrine becomes a kind of moral town hall: a site where grief, gratitude, petition, and civic pride meet. Peter Brown’s classic analysis of the cult of the saints helps explain why such local attachment was not incidental but structural: the holy dead functioned as enduring patrons, whose physical presence—tomb, relic, shrine—stabilised community and memory.

So when we encounter “Valentine of Terni”, we are encountering more than a biographical label. We are seeing how a city can hold a martyr’s name like a civic inheritance—one that may survive even when the historical contours blur.

Placidus, imprisonment, and execution

The Terni Valentine’s story, in the Roman Martyrology tradition as relayed by Vatican News, is stark and compact: he is severely beaten, imprisoned, and—when his captors cannot overcome his resistance—dragged out at midnight and beheaded on the orders of Placidus, the prefect of Rome.

This is precisely the kind of narrative that must be handled with an historian’s discipline. It should be presented as tradition, not as a stenographic transcript of imperial administration. A martyrology notice is a commemoration, not a dossier; names like “Placidus” may preserve genuine local memory, or they may reflect later attempts to lend concreteness to a story already revered. The value, therefore, lies less in overconfident reconstruction and more in what the tradition consistently insists upon: conflict with authority, endurance under coercion, and death understood by later Christians as witness.

It is also worth noting that even expert reference works acknowledge the entanglement here: authoritative summaries observe that the evidence “appears to refer to two Valentines”, one a Roman priest and the other a bishop of Terni taken to Rome and martyred—an ambiguity that neatly fits the possibility of overlapping cults and converging stories.

Why bishops become symbols in late antique storytelling

The shift from “priest” to “bishop” is not a decorative change. In late antiquity, bishops were increasingly public figures: moral authorities, civic negotiators, and, at times, unavoidable opponents of local power. A martyr-bishop, therefore, carries a particular symbolic charge. He represents not only personal holiness but the public courage of the Church embodied in a recognisable office.

Claudia Rapp’s major study of episcopal leadership in late antiquity is helpful here: bishops were not merely liturgical functionaries; they could become focal points of collective identity and conflict precisely because their leadership extended into the civic sphere.

In such a context, stories about bishops—especially stories of suffering under coercive authority—operate as narratives about community integrity as much as individual virtue. This does not prove every detail of the Terni Valentine’s martyrdom account. It explains why the tradition would naturally gravitate towards a bishop as a protagonist, and why a city might cling to such a figure with particular tenacity.

A martyr-bishop is, in miniature, a claim: that the Church can stand in public without borrowing its legitimacy from the state, and that the integrity of a community can be measured by the fidelity of its shepherd.

Who Was Saint Valentine, Two Valentines—or One? The Case for Confusion and Convergence

The honest answer to the question “How many St Valentines were there?” is this: at least two, as the Western liturgical tradition preserves them—one associated with Rome and the Via Flaminia, the other with Terni (Interamna)—both commemorated on 14 February.

From there, the historical puzzle begins to tighten.

On the surface, the two profiles are uncomfortably similar. Each Valentine is remembered as a Christian cleric. Each is linked with a healing miracle that provokes attention and, in later retellings, conversions. Each then meets the familiar martyr sequence: arrest, imprisonment, and execution by decapitation. Even the calendar conspires in their favour: both are placed on 14 February in the Martyrology tradition.

Geography adds pressure. Terni lies north of Rome, close enough for devotional memory to circulate and for cults to overlap; modern scholarly writing regularly places the region on the order of c. 80 km from Rome (the rough scale is what matters here, not a pedantic exactitude). In late antiquity, that is not “another world”; it is a plausible sphere for shared stories, pilgrims, and, crucially, the movement of relics and reputations.

This is where the cautious working hypothesis earns its keep: two cults—one Roman and one Umbrian—may have grown around the same martyr and diverged over time, producing a double tradition that later compilers preserved side by side rather than definitively untangling.

Equally, it remains possible that there were two distinct martyrs whose narratives converged because hagiography, especially when transmitted locally and later harmonised, tends to gravitate towards recognisable patterns: miracle, confrontation, suffering, witness, death. The point is not to force certainty where the sources are thin, but to name the options with discipline.

So, for the purposes of this article, we can hold a decisive but properly hedged conclusion: Valentine’s Day is built on a layered tradition—two Valentines in commemoration—and a real possibility that they represent either two closely linked martyr cults or one martyr remembered in two places.

The Lupercalia Myth: Why the Pagan-Origin Story Doesn’t Hold Up

The claim that Valentine’s Day is simply Lupercalia in Christian dress—a pagan fertility festival smuggled into the calendar with a halo pinned on top—has a certain irresistible neatness. Unfortunately, it is also the kind of neatness historians learn to distrust. In modern scholarship, attempts to present Valentine’s Day as a deliberate Christian “replacement” for Lupercalia are widely treated as evidentially thin, resting more on coincidence of season than on demonstrable continuity of practice or intent.

What we can say with confidence is that Lupercalia was a specifically Roman festival, with rites and meanings rooted in the city’s own mythic self-understanding. And we can also say that the late fifth-century pope Gelasius I condemned the continuing elite participation in that festival in a famous polemical letter (the Contra Andromachum), a text modern classicists analyse not as a cosy “Christianisation” programme but as a contested moment in the negotiation between old civic ritual and Christian identity.

What we cannot responsibly claim—without stronger evidence than is usually offered—is that Gelasius or the late antique Church constructed St Valentine’s feast as a functional substitute for Lupercalia. As Bruce David Forbes notes in a university-press study of major holiday traditions, there is no evidence that Gelasius promoted Valentine’s Day as a replacement for Lupercalia.

So why does the theory persist? Because it is the sort of story that flatters modern instincts: it is tidy (pagan festival becomes Christian feast), dramatic (blood rites transmuted into roses), and media-friendly (one paragraph, one villain, one reveal). It also carries an appealing whiff of contrarian sophistication: the comforting sense that one has discovered the “real” origin behind the public tale.

The corrective is less scandalous, but far better supported: the association between 14 February and romantic love is later and literary, emerging in medieval culture rather than late antique ritual. The crucial watershed is not a Roman festival but a set of medieval texts, most famously Geoffrey Chaucer, after which the “Valentine” theme takes on romantic connotations and begins its long migration into social practice.

How misinformation survives: the afterlife of a neat story

Misinformation rarely survives because it is complex. It survives because it is elegantly portable. “Valentine’s Day comes from Lupercalia” fits on a meme, fills a radio segment, and satisfies a modern appetite for origins that feel ancient and slightly illicit. Once a claim like that becomes culturally useful, it is repeated until repetition masquerades as proof. The historian’s task is not to sneer at the instinct, but to reattach the story to its sources—and, when the sources do not support it, to have the discipline to say so.

So When Did Valentine’s Day Become About Romantic Love?

If we strip the story down to what can be responsibly said, the change is less a slow river than a late turning: the romance of Valentine’s Day is not a continuous inheritance from a third-century martyr, but a cultural association that becomes visible much later—above all in the later Middle Ages, when courtly and literary habits begin to colonise the calendar.

That point is not merely modern scepticism dressed as sophistication; it is the verdict reached by specialist scholarship that actually tests the evidence rather than repeating inherited anecdotes. In his landmark study in Speculum, Jack B. Oruch argued that the familiar pairing of St Valentine’s feast with romantic love cannot be demonstrated in earlier tradition and emerges decisively with fourteenth-century literary usage, particularly in and around Chaucer. Henry Ansgar Kelly, working in medieval texts and cult history, likewise treats the “Valentine as patron of matchmaking” motif as a development that must be explained through medieval cultural forces rather than projected backwards into late antiquity.

This is the hinge on which the entire story swings. The Valentines of the Martyrology belong to a world of martyr commemoration—local cults, shrines, and the solemn honouring of witness. The Valentines of romance belong to a different engine: courtly love, seasonal symbolism, and the prestige of poetic fashion, where a feast day can be reimagined as a stage for choosing, longing, and devotion in an altogether new key.

So the most accurate answer is also the least melodramatic: Valentine’s Day becomes “about love” in the medieval period, not because an ancient festival was cunningly repackaged, nor because a third-century cleric left romantic instructions, but because poets and the culture around them began to treat 14 February as a day suitable for imagining love’s rites.

Chaucer’s Turning Point: The Parliament of Fowls and the “Mating Day” Idea

What Chaucer actually does in the poem

If you want the moment when Valentine’s Day starts behaving like Valentine’s Day, you do not begin in a catacomb. You begin in a poem. In The Parlement of Foules (often dated to the 1380s), Chaucer stages a dream-vision in which “Nature” presides over a vast assembly of birds.

The plot (such as it is) pivots on a courtly problem: choosing a mate. Chaucer plants the date with an almost casual firmness: “For this was on seynt Valentynes day, / Whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make …”

Within the poem’s own logic, St Valentine’s Day is the annual occasion when birds gather to choose partners—an imaginative “mating day” laid over the calendar like translucent vellum. It is not a folk custom being reported with journalistic neutrality; it is a literary device doing heavy symbolic labour.

Why poetry can rewrite a calendar

Martyrs die once; stories die rarely.

A feast day is, in essence, a commemorative date. Chaucer treats it instead as a stage direction. That is the trick: the saint’s day becomes not merely something you remember, but something you do. The calendar stops being a ledger of the dead and starts nudging the living—towards spring, towards desire, towards the social theatre of choosing and being chosen.

Scholars have long pointed to this poem as a key hinge in the history of Valentine’s Day: it gives later centuries a vivid picture to inherit, repeat, and eventually commercialise. And there’s a deeper point worth savouring: political regimes can legislate dates; poets can change what those dates mean. Empires can command obedience. A line of verse can command imagination.

The echo effect: 14th–15th century poets follow suit

Chaucer’s image did not remain politely inside Chaucer.

By the fifteenth century, Valentine-themed writing is not an eccentric one-off, but a recognisable literary fashion. Jean E. Jost (drawing on earlier scholarship, including the influential work of Jack B. Oruch) lists a cluster of poems written for St Valentine’s Day or trading on the Valentine conceit—works associated with late medieval courtly culture and its stylised language of love.

This is how cultural “common sense” is manufactured: not by a single author proclaiming a new ritual, but by repetition across writers, audiences, and social settings until the association feels older than it is. By the time Valentine language turns up in private correspondence, it is drawing on a literary atmosphere already thick with precedent.

From Poetry to People: When “Valentine” Became a Real Sweetheart

Chaucer gives Europe an image. The next step is more intimate: the image migrates from literature into lived practice—into the sort of writing not meant for posterity at all.

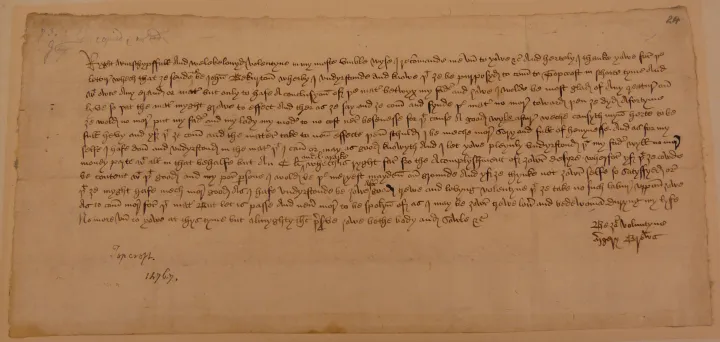

A famous early witness is Margery Brews’ letter to John Paston III, dated February 1477, in which she addresses him as her “right well-beloved Valentine” and signs herself as his Valentine. Modern historians regularly treat this as the earliest surviving Valentine greeting in English—not because it is the first love letter ever written (humanity was romantically reckless long before the Pastons), but because it preserves the word Valentine already functioning as a name for one’s beloved.

Two details matter for your reader’s sense of historical texture:

- It is personal and practical at once. The Paston-Brews match sits inside late medieval realities: family negotiation, dowry pressure, and reputational stakes. The Valentine language does not float free as pure sentiment; it is braided into the economics and anxieties of marriage.

- It shows the term in motion. By 1477, “Valentine” is no longer merely a saint’s name on a liturgical date. It has become a relational title—something you can call a living person, in ink, with intent.

This is the transition your article needs: from Chaucer’s birds choosing their mates in a dream, to real men and women using “Valentine” as a word that does social work—announcing attachment, requesting commitment, applying gentle pressure, and, above all, making the feast day speak the language of love.

Tokens, Notes, and the Birth of the Valentine Card (18th–19th Century)

By the time Valentine’s Day reaches the eighteenth century, the association with affectionate address is no longer confined to poetic circles or the correspondence of the gentry. It begins to appear as something closer to a social habit: a day that invites a small performance of feeling—sometimes playful, sometimes earnest, sometimes edged with embarrassment precisely because it is public enough to be recognised.

The 18th century: small gifts and handwritten verse

In eighteenth-century Britain and Ireland, and in parts of continental Europe, Valentine practice most commonly meant handwritten messages—short poems, riddles, compliments, and teasing declarations—often accompanied by small tokens. The key point is that the “Valentine” is still largely made, not bought. Its value is personal labour: your handwriting, your choice of words, your risk. This is why the tradition could feel both intimate and dangerous; it asks you to declare yourself, but under the cover of a date that gives you plausible deniability.

Historians of popular custom repeatedly note that Valentine’s Day became a recognised occasion for such exchanges before the dominance of mass-produced cards, with regional variations and a mixture of courtship and communal play. The day is becoming social technology: a culturally permitted pretext for saying what one might otherwise not dare to say.

The 19th century: commercial cards and mass tradition

The nineteenth century changes the scale. Improvements in printing, the growth of a consumer market for small luxuries, and—crucially—the expanding reach and reliability of postal systems create conditions in which Valentine messages can be standardised, decorated, and distributed widely. The Valentine begins its transformation from a private artefact into a commodity: something you select, purchase, and send.

This does not mean romance becomes less sincere. It means romance gains infrastructure.

Scholarly work on the history of greeting cards and nineteenth-century popular culture consistently treats the Victorian period as decisive for the rise of the commercial Valentine card, especially in Britain and the United States, where cheap print, decorative paper, and postal reform made sending cards easier and more socially routine.

This is also when the aesthetic of Valentine’s Day begins to harden into recognisable forms: lace-like paper cut-outs, hearts, cupids, florid typography, and messages that range from sincere devotion to pointed satire. (The comic and sometimes cruel “vinegar Valentine” belongs to this broader world as well: the day could be used to wound as easily as to woo, which is precisely why it was so socially potent.)

Why this matters for “origins”

This eighteenth–nineteenth-century shift is where modern Valentine’s Day truly becomes modern. It is no longer primarily a saint’s commemoration, nor merely a poetic conceit, but a widely shared social script supported by material systems—printing and post—that allow sentiment to travel.

And this, in turn, clarifies the larger argument of the article. The Valentines of late antiquity are martyrs remembered in local cults. The Valentine of the late Middle Ages is a literary reimagining that teaches the calendar a new association. The Valentine of the nineteenth century is a mass custom—recognisable to almost everyone, because it can be bought, posted, displayed, and repeated at scale.

What St Valentine Really Represents (If We Strip Away the Glitter)

Strip away the red foil/tissue paper, the price tags, and the rehearsed sentiment, and what remains is not a single tidy origin story but a layered one—like paint on an old church door, each coat added for a reason, none of them quite cancelling the last.

First, there are the saint(s): the Valentines preserved in the Church’s commemorative memory as martyrs, attached to specific places—Rome and the Via Flaminia, and Terni (Interamna)—and fixed to 14 February by liturgical remembrance. However, the biographies converge or diverge, the centre of gravity in these early notices is not romance but witness: a remembered death held up as a life that meant something.

Then there is the day: the date slowly acquiring a second life. In the late Middle Ages, Valentine’s Day begins to be used as a literary instrument—most influentially in Chaucer, who imagines it as the moment when birds gather to choose their mates. A feast day that once functioned primarily as commemoration becomes, in poetry, a social cue: a day that invites choosing, longing, and declaration.

Then comes the third layer: custom. What begins as a poetic association spreads, is repeated, and eventually becomes ordinary behaviour—tokens, handwritten verses, and, by the nineteenth century, the printed Valentine card carried by expanding postal and commercial systems. At that point, the tradition becomes scalable; it can be bought, sent, displayed, and repeated on a massive scale.

It is easy to tell this story with cynicism—saint becomes poem, poem becomes product—but that is a thin sort of cleverness. Devotion and romance are not enemies here. They simply arrived at different times, and they do different work. The martyr tradition speaks the language of memory, fidelity, and the cost of belief. The romantic tradition speaks the language of attachment, hope, and the human urge to mark love with ritual. The commercial layer, for all its excess, is also evidence of something enduring: people continue to want a set day on which affection is not merely felt but spoken.

Valentine, then, is less a single historical figure standing behind a modern festival than a meeting-point where three forces intersect: the Church’s remembrance of witness, the poet’s ability to re-enchant a date, and the public’s habit of turning private feeling into shared custom. That is what survives when the glitter flakes off—and it is, in its way, more interesting than the legend.

From Medieval Europe to Whitefriar Street: How St Valentine’s Relics Ended Up in Dublin

As Valentine’s cult spread across medieval Europe, his body began to multiply.

By the High Middle Ages, churches and monasteries from Rome to the Atlantic fringe claimed custody of relics attributed to St Valentinus, most commonly fragments of the skull. The logic was devotional rather than anatomical. Saints were not preserved as forensic wholes but distributed as presences, their remains divided so that many communities might claim proximity to sanctity.

Rome, predictably, anchors the tradition. Santa Maria in Cosmedin still displays what is presented as an entire skull of St Valentine, an arresting reminder that relic veneration is not a metaphorical practice but a physical one. From there, the trail splinters.

Medieval and early modern sources—most systematically catalogued by the Bollandists—record claims to smaller fragments across Europe: San Antón in Madrid, Whitefriar Street in Dublin, the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Prague, St Mary’s Assumption in Chełmno, as well as churches in Malta, Birmingham, Glasgow, and even the Greek island of Lesbos, among others.

To modern eyes, such proliferation invites scepticism. To medieval Christians, it required no defence. Relics were not souvenirs of the past but instruments of the present—material assurances that the martyr remained active, attentive, and near. Possession of a saint’s remains meant access to protection, intercession, and power. One Breton episode from the eleventh century makes the logic plain.

A bishop there was said to deploy what was revered as Valentine’s head against a catalogue of threats: fires were halted, epidemics checked, illnesses cured, and cases of demonic possession resolved. Whether these reports persuade the historian is almost beside the point. They show how Valentine functioned—not as a romantic cypher, but as a working saint, called upon in moments of communal danger.

The Whitefriar Street shrine

It is within this wider economy of relics—distributed, contested, and fervently believed—that the story of Valentine in Dublin belongs. The Whitefriar Street shrine is not an eccentric outlier, but a late and particularly well-documented chapter in a much older pattern: the afterlife of a martyr whose authority travelled, quite literally, bone by bone.

If Rome is the grand archive of the saints, Dublin is where one of Valentine’s most curious afterlives took root. The story does not begin with lovers, but with a Carmelite: Fr John Francis Spratt (1796–1871), a prominent Dublin priest and public figure in the city’s nineteenth-century Catholic revival.

In 1835, Spratt travelled to Rome. Carmelite accounts emphasise his reputation as a preacher and the impression his sermon-making created in Roman clerical circles. What matters historically is not the romance of the anecdote, but the consequence: Pope Gregory XVI (r. 1831–1846) authorised a gift to Spratt—relics identified as belonging to St Valentine, enclosed in a reliquary.

What arrived in Dublin, and what relics mean

Carmelite sources describe a small chest and inner container holding “some bones” and a vessel “tinged with blood”, sealed in Rome before being dispatched to Ireland. Whatever one makes of relic authentication in general, this at least gives you the correct category of object: not a medieval legend, but a nineteenth-century transfer of a physical devotional artefact, treated as “corporeal relics” by its custodians.

The 1836 procession—and the Dublin context

The reliquary reached Dublin in November 1836 and was brought in procession from the North Wall to Whitefriar Street (Carmelite Church). That public movement matters: in an era when Catholic visibility in Ireland was newly assertive after Emancipation (1829), devotional display could carry social and political charge as well as piety. In other words, “fervour” and “backlash” are not rival stories; they are often the same story told from different pavements.

Why visitors still come

The shrine did not become famous because medieval lovers queued obediently through the centuries. It endured because religious places acquire second lives: moments of renewed attention, periods of neglect, restorations, rediscoveries. Today, Whitefriar Street’s Valentine shrine functions as a living devotional site and a cultural curiosity—visited by pilgrims, tourists, and the romantically hopeful, all tugged by the gravitational pull of a name that literature later set ablaze.

“Yet the Dublin shrine is a modern chapter in a far older problem: the sources can tell us who was commemorated, but rarely deliver a tidy biography.”

Frequently Asked Questions: Click a question to read about St Valentine

Was St Valentine a real person?

Yes, in the sense that the Church’s official commemorative tradition preserves Valentine(s) as martyrs. What is uncertain is not whether “Valentine” was commemorated, but which historical individual(s) stand behind the later, expanded stories.

How many St Valentines were there?

The Roman Martyrology preserves two Valentines in Italy commemorated on 14 February: one associated with Rome (Via Flaminia) and one with Terni (Interamna). Some scholars and reference works note that these may represent either two distinct martyrs or one martyr remembered in two local traditions.

Why is Valentine’s Day on 14 February?

Because 14 February is the fixed day of commemoration for Valentine(s) in the Roman Martyrology. The date is therefore liturgically anchored as a feast/commemoration day, even if the precise historical circumstances behind the date are not fully recoverable.

Is Valentine’s Day based on Lupercalia?

No credible evidence shows Valentine’s Day was created as a Christianised continuation or replacement of Lupercalia. Modern historians generally treat the claim as an attractive but weakly supported theory, and scholarship notes there is no evidence that Pope Gelasius promoted Valentine’s Day as a substitute for the pagan festival.

When did Valentine’s Day become romantic?

The romantic association becomes clearly visible in the medieval period, especially from the fourteenth century onward, rather than as an unbroken tradition from the third-century martyrs. Academic studies, particularly on medieval literature and custom, locate the decisive shift in late medieval courtly and poetic culture.

What did Chaucer have to do with it?

Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules presents St Valentine’s Day as the day when birds gather to choose their mates, a highly influential image that later writers echoed. Scholarship has long treated this as a major turning point in the development of Valentine’s Day as a romance-themed occasion.

Bibliography for Further Reading:

Primary/official ecclesiastical sources

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Martyrologium Romanum: Editio typica altera. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2004.

- Collectio Avellana. Letter 100 (Adversus Andromachum / Contra Andromachum), in CSEL 35 (critical edition). (Primary text for Gelasius’ anti-Lupercalia letter; cite the specific CSEL volume/page range once you finalise your edition details.)

Peer-reviewed scholarship and academic books

- Brown, Peter. The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Forbes, Bruce David. America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0520284722.

- Jost, Jean E. “Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules as a Valentine Fable: The Subversive Poetics of Feminine Desire.” In Parentheses: Papers in Medieval Studies (1999): 54–82.

- Kelly, Henry Ansgar. Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine. (Brill; cite the specific edition/year you are using—this work exists in more than one publication form.)

- McLynn, Neil. “Crying Wolf: The Pope and the Lupercalia.” Journal of Roman Studies 98 (2008): 161–175.

- Oruch, Jack B. “St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February.” Speculum 56, no. 3 (July 1981): 534–565.

- Rapp, Claudia. Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity: The Nature of Christian Leadership in an Age of Transition. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

- Walsham, Alexandra. “Introduction: Relics and Remains.” Past & Present 206, Supplement 5 (2010): 9–36.

- Whelan, Kevin. “Sectarianism and secularism in nineteenth-century Ireland.” In Paul Brennan (ed.), La sécularisation en Irlande, 71–90. Caen: Presses universitaires de Caen, 1998.

- Wycherley, Niamh. The Cult of Relics in Early Medieval Ireland. Turnhout: Brepols, 2016.

Expert reference works

- Farmer, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Oxford Reference (OUP). “Martyrology” (reference entry; cite URL/access date in your preferred style).

Dublin relics: institutional/archival custodial sources (expert, non-peer-reviewed)

- D’Arcy, Fergus A. Raising Dublin, Raising Ireland: A Friar’s Campaigns. Father John Spratt O.Carm. (1796–1871). Dublin: Carmelite Publications, 2018.

- Dictionary of Irish Biography. “Spratt, John Francis (1796–1871).”

- Irish Province of Carmelites. “The Shrine of Saint Valentine” (Whitefriar Street history and 1830s transfer account).

- Rafferty, Oliver. Review of D’Arcy, Raising Dublin, Raising Ireland. Irish Historical Studies (Cambridge University Press), 2019.

- Whitefriar Street Church (Carmelite), Dublin. “Saint Valentine” (custodial page for the shrine).