Introduction to the Myth of Mary & Jesus in France

We start this article with questions such as: Where is the grotto of Mary Magdalene? Were Mary Magdalene & Jesus buried in France? Is that really Mary Magdalene’s skull? Is there a saint called Maximin? And what was Mary Magdalene known for? We will endeavor to answer these questions and more. We cover topics such as Saint Sara and the Saint Marys arriving by sea to the south of France and the modern myth of Jesus in France, with historical facts and expert academic references. We include writings and accounts from popes, Benedictine monks, and the gospel of Mary & the gospel of John. Translations from the original French source material for the first time made available in the English language regarding the young woman named Sara/the women saints and their sea journey by boat to the town Sainte-Marie-de-la-Mer where thousands of gypsies crowd in this Mediterranean sea region of France every year.

Furthermore, we discuss gypsies and gospels from the New Testament and explain creational myths from France, Spain, the holy land, and the United Kingdom. Also, this article includes local legends from the region known as the Camargue and odd towns such as Saint Maximin-La Sainte Baume. Women flock on pilgrimage to many other French towns; they visit not only the town churches but crowd to surrounding sites where there is a grotto or crypt dedicated to Mary and, by doing so, meet other pilgrims, make friends, and create massive online communities with one another.

These women show devotion to Mary, but few ask questions or make inquiries into the information given to them on the internet or by their anglophone tour guides. Hence, it was decided a detailed, impartial article was needed to assist all pilgrims and help them make their own decisions so as not to rely on outdated and misinformed research by people searching to profit from these people on pilgrimage where they might have a lack of knowledge on the subjects covered. The French Tourism offices (most speak excellent English) found in each town are full of current information and data regarding all pilgrim sites in France. There is no excuse for misinformation these days; these offices will even recommend great reading material. French libraries are also astounding, extremely helpful, and full of historical and academic books. Hence, there is no excuse for foreign researchers, authors, or tour guides to make mistakes for these pilgrims when writing on French history.

Provence & La Sainte Baume

The main places of pilgrimage and worship in France are Saint-Maximin, La Sainte Baume, and Vézelay, where there are relics of Mary Magdalene. Mary Magdalene supposedly arrived by sea with Mary Jacobe and Mary Salomé at Saint Marie-de-la-Mer in Provence, France. Tour operators, numerous lecturers, and authors use legends and stories to justify a hidden history of the descendants of Jesus and Mary Magdalene in France. Although many use manipulation to prey upon peoples’ sensitivity and ignorance of French historical history, these legends are beautiful and well-sold. “One of the goals of the hagiographer (a writer of the lives of the saints) is to persuade the audience and readership of life of its historicity.” Monique Goullet, Écriture et réécriture hagiographiques: Essai sur les réécritures de Vies de saints dans l ‘Occident latin médiéval (V/lf – XlIf s.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2005, p. 172.

Unassuming tourists and visitors that arrive on tours or followers of anglophone websites/books/documentaries fall prey to regional literature (local poetry, myths, and legends in literature, etc.), some of which the French church (pre-French revolution), not the Vatican, initially set up to attract pilgrims. Sadly, many people make vast profits from these tourists as there is a lack of up-to-date information available in the English/American language. Many rely on what is now seen as outdated French source material, with the English and the Americans still relying on older French books, not the most recent. It is mainly the new-age Anglo-American far-left “feminist” current that propagates these myths and legends for their political needs. Because of this, we find many none left feminists sadly falling into exploitative situations that require large amounts of money, which pass into the hands of the unscrupulous tour companies/guides who speak the French language very well but refuse to use readily available updated French research for the content they sell.

Some people have exploited the truth to set up or run businesses from France to profit from people wanting to travel to cult and pilgrim sites of Mary, Sara, and, more recently, Jesus within France. Many also write on the role of women within the church and want to open the priesthood to women, “which in fact has never been closed to women when Christianity is understood correctly”. Gnostic teachings and priesthood are fully open to women from a theological perspective; the debate on priesthood within Christianity is based on philosophical and allegorical viewpoints. Within France, there are some wonderful Gnostic churches fully open to women as priests.

This is What the Historical Research Says

The current historical research is unequivocal; there has never been Mary Magdalene at either Saint-Baume or Vezelay. The legendary character of many “saints” and their relics is well known. “In the light of this brief overview of the historiography concerning the evolution of the hagiographic discipline and, by extension of the historicity of the apostolate of Palestinian saints in Provence, we might consider that the concerns of scholars who were the artisans do not match those of today’s academic historians.

While for the former, it is essential to debate the historicity of traditions Provençal, there are no academics nowadays, to our knowledge, that discuss these questions. It should be borne in mind, however, that concerns change because the research is evolving. If we no longer seek to establish that Provençal traditions are not historical, it is because the demonstration has been made”. Annie et Véronique Olivier « Les sources et la tradition dans la Vie de sainte Marthe de Tarascon attribuée à Marcelle (BHL5545): articulation et utilisation » p19. dir., Actes du colloque: L’édition de sources manuscrites. Revue Le Manuscrit, 2009.

The Relics of Mary Magdalene in Vezelay and Saint-Maximin

Initially, there was another dispute regarding the relics of Mary Magdalene between Vezelay and the town of Saint-Maximin and La Sainte Baume. We will now explain it by using expert research and referencing. The oldest testimony seems to come from the chronicles (Gestes des évêques de Cambrai) written in three books by a Canon of Cambrai church between 1041-1043 AD; we have this revelation which says that from Leuze Abbey church of the Diocese of Cambrai. Among them, he cites the collegiate church of Leuze, which named Saint Amand, as founding it under the patronage of the apostles St. Peter and St. Paul.

“Leuze was a wealthy abbey in which rests the sanctified man of God, called “Badilon”. It is he, they say, who brought from Jerusalem to Vézelay in Burgundy the body of Saint Mary Magdalene”. The tradition in the West of the character composed by Pope Gregory (540-504) takes the name “Mary Madeleine” (Mary Magdalene). She is, for him, the “symbol of converted gentility”; also, she represents mystical love and the penitent Magdalene. (See also the gospel of Mary amongst other gospels.)

The Allegorical Mary Magdalene

Pope Gregory the Great created this allegorical Mary Magdalene to represent his time’s philosophical and political goals, similar to the Jewish Midrashic tradition. The union of the three characters (Mary’s) into one took place until the period of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, which brought a critique of the life of the saints due to the development of scholarship and criticism. It was an attack on the beliefs of the early church. Mary Magdalene was considered to be the union of the three characters until Lefèvre d’Etaples in 1517, and then again in 1519, disputed this theory. It was condemned by Sorbonne, which required him to teach the uniqueness of the three “Marys”.

The Myth Starts With Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

The legend of the saints and Marys that came to shore to this place by boat. They were close disciples of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, Lazarus and sister Martha, Maximinus, Joseph of Arimathea, Mary Salome, Mary Jacobi, and one young “Egyptian” serving woman named Sara/Sarah (patron saint of the gypsies called Sara La Kali). “For the questions” – did Jesus have a child with Mary Magdalene? Who was Jesus’s wife? You can find answers within the dedicated Mary Magdalene article here. The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife. The myth of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and the invention and legend of Mary in Provence are included in the dedicated linked article below. Where you find answers to the questions: Was this legend created by the church or not? Why was this place so special? The linked article Sara la Kali.

Victor Saxer and His Historical Research

We have to thank the expert Victor Saxer among others that do historical research about the Provinçial legend. Victor Saxer (1918, 2004), Doctor of Theology, will reprise Duchesne’s work in his thesis. Before the 11th century, there was no record of a Mary Magdalene cult or these saints’ arrival in France. Le culte de Marie Madeleine en Occident: Des origines à la fin du moyen âge, Cahiers d’archéologie et d’histoire 3 (Paris: Clavreuil, 1959), p31. Historical research continues to this day with experts such as Guy Lobrichon and Élisabeth Pinto-Mathieu.

Excavations conducted in 1994 by the great historian of The Ancient Provence Jean Guyon, director of research at the National Center for Scientific Research (born 1945), confirm, by the discovery to the south of the basilica, a 5th-century church and a baptistery of the 6th century, the hypothesis of a place of worship built by and for a family of notables wishing to Christianise all the peasants. Guyon Jean. Les premiers monuments du culte chrétien de Saint-Maximin (Var). Bilan de deux campagnes de fouilles (1993- 1994). In: Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France, 1994, 1996. pp. 285-295; DOI.

As for the mausoleum, whose Christian-themed sarcophagi are typical of the 4th century, there is no record of a Christian cult until the 3rd century. Jean Guyon says in an interview, “I am sorry to say that the legends of the saints of Provence have no historical basis, although I understand, as Provençal, that one can be attached to this tradition.” Saint-Maximin was a cult center on a large scale, although the particular aim escapes us. Was this a parish created by the church to serve a small agglomeration? Or a place for a cult on their property by village leaders whose tombs are perhaps in the immediate vicinity, or in the sarcophagi placed within the mausoleum in which Charles de Salerne (future King Charles of Naples) invented in December 1276 the relics of the Madeleine?

The Cult of Mary in England: Does it Predate the French?

As we have found from research, there was a much earlier cult of Mary in Ireland and England, predating all the cult sites and reliquaries in France. There is even a tradition that the Jesus family arrived by sea from the holy land. The evidence we discuss here is from just over a thousand after the crucifixion of Jesus.

King Athelstan

The Reliquary Cross in the above photo is one of the few surviving relics that provide evidence of the lavish church furnishings of pre-Conquest England. The presence of fragmentary and illegible markings on the edge of the cross suggests that the cavity beneath the ivory figure of Christ had previously housed other relics of saints before the insertion of the ivory figure of Christ. This ivory statue of Christ was removed from its pedestal to allow for photography; in doing so, a finger was found in a hollow cut in the wood. A finger relic was not uncommon in England in 932, even though Pope Innocent III forbade the dismemberment of saints. King Athelstan donated a third of his extensive collection of relics to the Exeter monastery, the church of St. Mary and St. Peter. One of the gifts included a finger supposedly from Mary Magdalene.

Written on the Cross

IHS NAZARENUS RELIQVIE LIGNI.VLQ DE.O ET CAMIN.IHS.XPS AMD NIS / /RV.EDA.DI.DI SIMEONIS ET MAR. This Cross is now housed in The Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

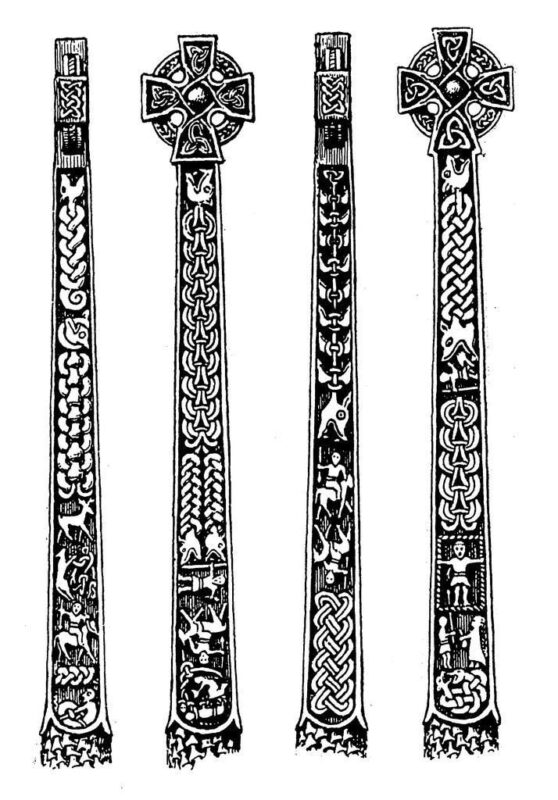

The Gosforth Cross

The Gosforth Cross St Mary’s churchyard in Cumbria is the most well-known of the monuments built in Anglo-Saxon England during the period of Scandinavian settlement in the late ninth and early tenth centuries, which shows the victory of Christ over the Heathen Gods. According to Bailey and Cramp, the complete cross-shaft dates to the first half of the tenth century and is a member of a group of round-shaft derivative crosses that can be found throughout the English counties of Lancashire, Cheshire and Western Yorkshire, as well as the Peak District of Derbyshire and Staffordshire. Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 101–3. Calverley identified the cross-shaft with the mythological Ash tree Yggdrasil, proposed Scandinavian mythological identifications for each figure carved on the four faces of the cross, including Loki and Sigyn on one of the faces, and conflated Christ with various members of the Norse pantheon. Calverley 1883, pp. 377–381.

We see allegorical figures on this particular cross, which began to be depicted in England around the year 830 A.D and were identifiable by their typical arrangement to either side of the cross, with Ecclesia on Christ’s right, facing him and Synagoga on Christ’s left, facing away from the cross (Schiller 1972, pp. 110–13). It appears unlikely that our feminine figure was intended to represent Ecclesia, even though she faces the cross and is situated to Christ’s left, but given her position on the ‘wrong side of Christ, it is possible that she did carry Christian associations. As a result, Bailey has suggested that she should be identified as Mary Magdalene carrying her alabastron, an appropriate counterpart to Longinus, with both figures symbolizing the converted heathen and the recognition of Christ’s divinity. Bailey 1980, pp. 130–31; Bailey 2000, pp. 20–21; Bailey 2000, p. 20

Here, although she does not carry an alabastron, she carries a horn. Liturgical uses of horns may be relevant to understanding how this feminine figure was viewed and understood by contemporary audiences. Although never used as chalices for performing the mass in the Anglo-Saxon Church, horns were used in services for the ordination of minor orders by the late tenth century, as recorded in Old English glosses to the late tenth- or eleventh-century Anderson Pontifical (London, British Library, Add. MS 577337; Neuman de Vegvar 2003, p. 249. They are likewise mentioned in Anglo-Saxon hagiographies for dispensing consecrated liquids, such as water, among the catechumens. They are recorded as containers for the oil blessed by bishops and used for various anointings in later medieval texts. Neuman de Vegvar 2003, pp. 249–50.

Therefore, this range of uses demonstrates how contemporary Christian audiences may have interpreted the horn carried by the female figure at Gosforth. Meaning that, first, it is unlikely she would have been interpreted as Ecclesia, for this allegorical figure is associated with the Eucharist, thus representing the liturgical ceremony from which horns were apparently excluded. Second, the liturgical use of horns as vessels for consecrated liquids supports Bailey’s suggestion that contemporary audiences could have viewed the Gosforth figure as representing Mary Magdalene with her alabastron, understood to signify the converted Christian.

Furthermore, this would also explain her depiction alongside Longinus, another formerly non-Christian figure, beyond the frame enclosing Christ, suggesting, at the very least, that the pair would be appropriate and relevant iconographic choices to include in a Crucifixion scheme, given the ongoing conversion and Christianisation of incoming Scandinavian groups during the late ninth and tenth centuries, which likely formed the intended audience for this monument, as indicated by the selection of a traditional Scandinavian female figural-type. Moreover, such associations involving the phenomena of conversion and Christianisation seem to be supported by other horn-bearing figures in Anglo-Saxon art. In late Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, horns are consistently depicted as attributes of figures who appear in negative contexts as symbols of vanitas or to indicate that the figures are pre-Christian sinners. Neuman de Vegvar 2003, pp. 241–44.

Longinus was associated with (Roman) traditional beliefs until his apparent conversion after the Crucifixion (gospels John 19: 34–37; Mark 15: 39–40; Matthew 27: 54; Luke 23: 47). It appears that the Gosforth sculptors used the framing device to communicate to contemporary audiences that, although these three figures belong to the same narrative moment, the lower pair are distinct from Christ and, by extension, were to be associated with traditional beliefs, initially excluding them from the salvation facilitated by Christ’s sacrifice. The Gosforth frame, used to denote an icon, prompts the viewer’s compunction, this emotional response enabling them to perceive the two figures below, associated with sight, conversion, and recognition, as standing before an icon. Together, these features would convey to the viewer that they should respond mimetically by contemplating the image, gazing upon Christ-as-cross, and adopting an appropriate attitude of adoration elicited by contemplation.

Thus, this would, in turn, inspire prayer, potentially in supplication for their salvation, encouraging a secondary mimetic response. In an attitude of prayer, the viewer would adopt the orans pose, which assimilated their body with that of Christ on the cross. Peers 2004, p. 13. For a viewer of the Gosforth, Crucifixion to adopt the pose would thus create a ‘living image’ of the framed carving of Christ before which they stood. Christ and his presence were understood to be implicit in all forms of the cross, which included the imitative pose of the position of prayer. An interruption to this posture was considered the equivalent of losing bodily and intellectual contact with God. Peers 2004, pp. 27–28. In this context, the Gosforth image of Christ in the cruciform pose would encourage the viewer to maintain their attitude of prayer, thus increasing their contact with the divine, made present by the contemplation of the iconic image before the viewer, its framed image of Christ creating a threshold between the human and divine worlds and emphasizing Christ’s role as victor over death. We have to thank Amanda Doviak for her academic work on the Gosforth Cross. Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross by Amanda Doviak.

The Village of Rennes-le-Château

We will not include any myths regarding Mary and Jesus coming to this place. There is no evidence whatsoever of either a cult center or reliquaries of Mary or Jesus there. All sites with items linked to Jesus or the crucifixion of Jesus are very well documented. All sites that have had items such as a thorn from the crown of thorns of Jesus, pieces from the true cross of Jesus, and, of course, the holy blood of Jesus are all significant pilgrimage sites. We deal with this new age myth of Jesus and or Mary in France and linked to the village Rennes-le-Château in the article The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife.

Conclusion

In his work, On the Myrrh Bearers, the patriarch of Jerusalem, Modestos (630-634), says Mary Magdalene returned to Jerusalem, where she lived with the Virgin Mary/Theotokos until her dormition/death. Mary Magdalene then went to Ephesus, where she supposedly lived out the rest of her life. Gregory of Tours (538-594) described her tomb outside the city in his De Miraculis. Gregory himself had not seen the tomb himself but was recounting the testimony of an unnamed “Syrian traveller.” Her relics were transferred in the 9th century to Constantinople in the monastery Church of Saint Lazarus. Later in the era of the Crusader campaigns, they were taken to Italy in Rome underneath the Lateran Cathedral altar. Her incorrupt hand is preserved in the Simonopetra Monastery on Mt Athos. From there, she is then found in specific sites in France.

By visiting ancient cemeteries whose inscriptions were still often legible at the time. In the cemetery of Sens, he must have found ancient tombs with the names of Savinianus, Potentianus, Altinus, and Eodaldus. Wénilon (Archbishop of Sens 836 or 837) made excavations and discovered that the tombs concealed skeletons (which were not intact and indicated violent deaths). Convinced of having discovered the bones of the evangelisers of the country, the Archbishop had their bodies exhumed, which were solemnly placed in a new tomb on August 25, 847 A.D. They created a feast commemorating their martyrdom. As the date was not known, it was set for December 31, the day of the martyrdom of a famous local saint – Colombe – attested to the Hieronymian lodge from the end of the fourth century. As we see by this great work of Nicolas Balzamo, many Saints were totally invented to suit social and political interests to have a prestigious past linked with the past apostolic times and the direct followers of Jesus Christ. Nicolas Balzamo LES DEUX CATHEDRALES Myth et histoire â Chartres (XI-XX siêcle) éditions Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2012, p50.

As we have read, this poor woman, Mary Magdalene, has traveled both dead and alive at multiple sites at similar times throughout these legends. The only reliable thing we know is that she never came as a living person to France. For any of her relics, we need only to look to scholars in hagiography and such experts as Victor Saxer to understand the complicated cults of saint’s bones. Most of the sites, such as Vézelay Abbey, Sainte-Baume, and Rennes-le-Château, were originally dedicated to the Virgin Mary, “the mother”, then later to Mary Magdalene. To also clear up the massive misunderstanding of Mary and Sainte-Baume and the name “Baume”, which means grotto/cave (Saint Mary of the cave), not meaning Saint Mary of the Balm. Historically, until 1170, the patron Saint of the grotto/cave of Sainte-Baume in France was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and not Mary Magdalene. Karen Ralls, Medieval Mysteries: A Guide to History, Lore, Places and Symbolism.