Ecclesia and Synagoga Motif: Shekhinah and Mary Magdalene? From Strasbourg Cathedral to La Rochefoucauld

Ecclesia and Synagoga (Ecclesia et Synagoga in Latin), meaning “Church and Synagogue”: Medieval Christian art and Gothic cathedral sculptures of these female figures. How did these veiled sisters of the covenant become so misunderstood? Today, modern esoteric narratives totally misread them, from their stone portals on the façade of Strasbourg Cathedral to the stained glass of the chapel in the Château de La Rochefoucauld.

Synagoga and Ecclesia: Two Veiled Sisters in Medieval Art and Gothic Cathedrals

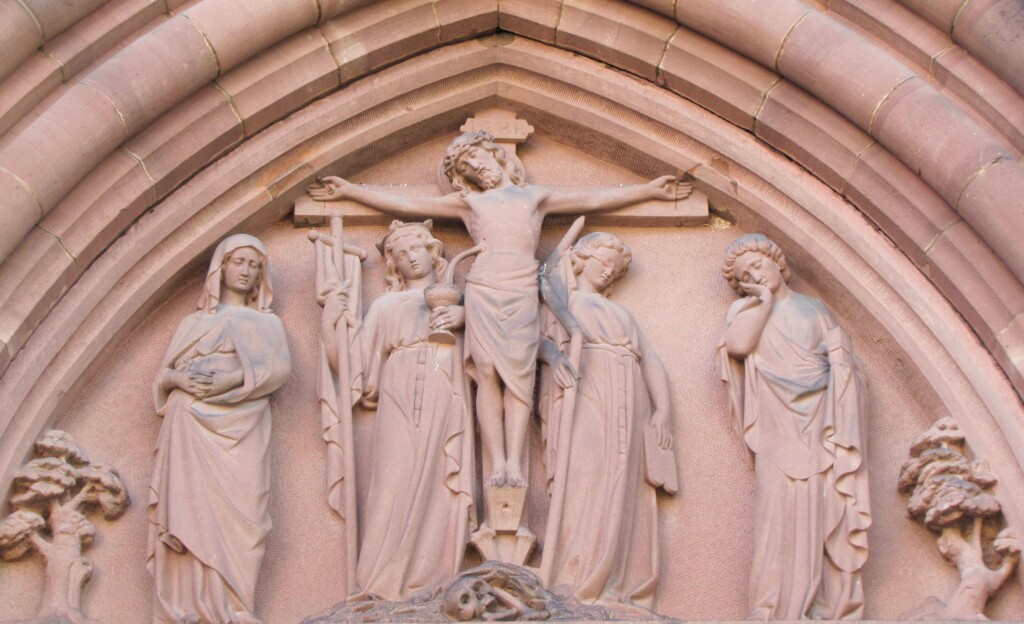

At the threshold of a forgotten cathedral cloaked in mist, two sisters eternally wait, silent sentinels carved from the ageless stone of faith. One is crowned with splendour, eyes fixed heavenward, her gaze illuminated by certainty. The other stands blindfolded, her expression serene but sorrowful, hands desperately clasping a slipping scroll, poised between loss and longing. They are Synagoga and Ecclesia, ancient symbols etched deep within the heart of a Roman Catholic teaching and Christian imagination, figures embodying the mystery, tension, and kinship between Christianity and Judaism.

More than allegory, these sculpted sisters are spectral presences within the cathedral of history, whispering through the corridors of theological time. From their earliest medieval appearances in the 9th century, they emerged as allegorical embodiments of the two covenants: Ecclesia, representing the triumphant Church, and Synagoga, embodying the people of Israel. Their stone gazes silently guided generations of pilgrims, merchants, and peasants who wandered through Gothic cathedrals, shaping not only theology but the very imagination of medieval Europe.

Yet Ecclesia and Synagoga are not static relics of a forgotten past. They remain part of a living debate, constantly reinterpreted across centuries of art, theology, and ecumenical dialogue. Their imagery has been both a vehicle for division and a seed for reconciliation. At times, the figures expressed triumphalism and exclusion; at others, dignity and mystery. To follow their story is to walk through the uneasy relationship of Christianity with its Jewish roots, a path winding through prophecy, stone, persecution, rediscovery, and reconciliation.

And this story is not confined to the great cathedrals of Strasbourg or Bamberg. It finds a quieter but equally poignant expression in the Château de La Rochefoucauld in Charente, France, where modern stained glass, a family tragedy, and a misidentification of Ecclesia as Mary Magdalene have given new resonance to this age-old allegory.

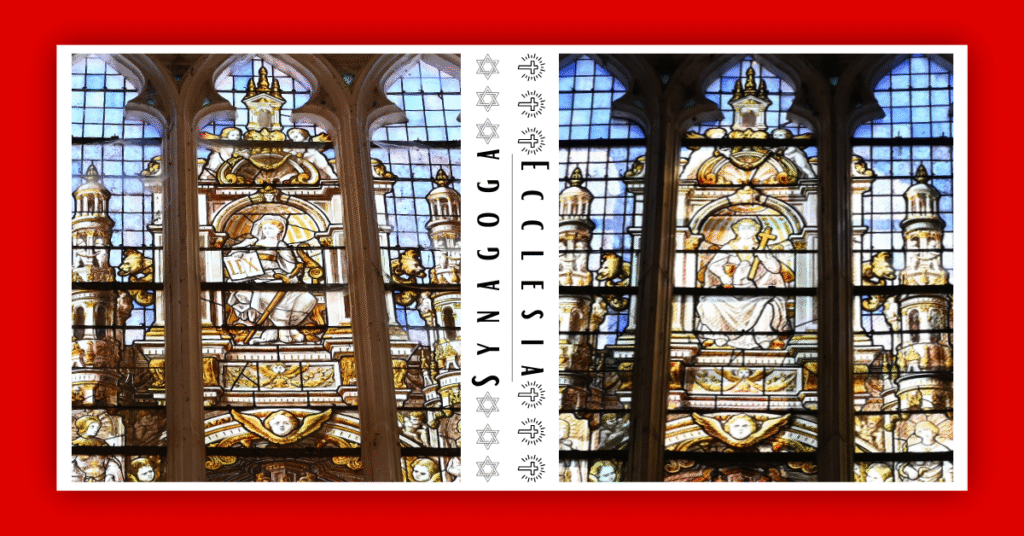

Ecclesia Misidentified as Mary Magdalene: Reading Stained Glass at the Château de La Rochefoucauld

In the quiet chapel of the Château de La Rochefoucauld, visitors often pause before a luminous stained glass window depicting a woman, seated upon a throne and holding the sacred emblems representing the Church. To the casual observer, the scene seems familiar; however, there are those who hastily identify the figure as Mary Magdalene. The Magdalene’s popularity in French devotional culture has long influenced interpretations of female imagery in Christian art, especially in Provence, where her mythical relics were venerated. Read our dedicated article for Mary in France: Cultus of Mary Magdalene, Sara & Jesus, The 1st Sacred Pilgrimage. Yet the figure here is not Magdalene at all, but Ecclesia: the personification of the Church. See our dedicated article on Mary the Mother with the Grail. Mary Magdalene and the Holy Grail: The Magnificat and her Chalice.

The window is part of a relatively modern ensemble and not a survivor of the Renaissance, installed in the 20th century after the tragic death of François XVII de La Rochefoucauld (1905–1909), the young heir of the line. His parents, François XVI, Duke of La Rochefoucauld (1853–1925), and his American wife Mattie-Elizabeth Mitchell (1866–1933), remodelled the chapel in mourning, replacing its stained glass, altering its floor tiles, and inscribing their son’s youthful face and initials throughout the décor. Today, François XVII and his parents rest together in the chapel’s tombs.

This act of memorialisation overlays layers of Renaissance and medieval tradition with a distinctly modern story of grief and remembrance. It shows how even in the 20th century, families of ancient nobility continued to shape sacred spaces, transforming them not only into monuments of lineage and piety but also into tender shrines of mourning. The La Rochefoucauld chapel thus stands as a palimpsest of faith and memory, where the triumphal iconography of Ecclesia is refracted through the sorrow of a family’s personal loss, long after the medieval age of cathedrals had passed.

Earlier, the chapel’s history already bore marks of transition. François II had died in 1533, leaving his heirs to complete its work. The structure itself is architecturally distinctive: ogival vaults set on columns inspired by Italian models, frustums of entablature stacked above capitals to create greater height while preserving antique proportions. The very building is a hybrid of classical memory and Renaissance experimentation, a stage upon which later glass and imagery would play their theological roles.

Within this layered history, the stained glass figure of Ecclesia has often been misunderstood. She is enthroned not as a penitent, like Magdalene with her jar of ointment and the memory of Golgotha, but as a queenly bride of Christ. The chalice in her hand signifies the Eucharist; the Cross proclaims the Church’s victory in the Passion; the throne affirms her institutional authority; when shown with a crown, it emphasises sovereignty; the shell-like niche situates her within baptismal grace. To mistake her for Magdalene is to confuse allegory with hagiography, and triumphal institution with individual sanctity. The blame for this confusion in modern times within esotericism lies solely on the “Fantastic Realism” literature found in books such as The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, by Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent, and Richard Leigh.

Yet this misreading is doubly ironic, because it rests on a figure that the earliest Christian traditions do not, in fact, know in this guise. As Thierry Murcia has shown in his detailed peer-reviewed study of “Mary called the Magdalene”, the late-Latin image of a separate, eroticised Magdalene from Magdala owes more to medieval preaching and modern fantasy than to the Gospels themselves. In several ancient strands, the Marian figure at the Cross and the Tomb is Mary the Mother – Mary the “Magnified” of the Magnificat – not the romantic heroine beloved of feminist or “Fantastic Realism” esoteric literature. In that light, the Rochefoucauld window returns to its proper meaning: Ecclesia as Mary-Church, not as a Grail-coded “Magdalene”. For more on Mary the Magnificat, see our dedicated article: The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife

Ecclesia and Synagoga in Stained Glass: La Rochefoucauld Chapel, the Virgin Mary, and Saint George

The stained glass within the Rochefoucauld chapel creates a dialogue not only between Synagoga and Ecclesia, but between multiple layers of Christian iconography. On one side (right), Ecclesia appears in her triumph. Opposite her (left), Synagoga is still holding the “Tablets of the Law” as they seem to slip from her grasp. Beneath Synagoga, however, is another striking image: the Virgin Mary. Here, the allegorical sisters are no longer isolated abstractions but situated within a larger Christian family, as if to remind the viewer that even the Church and the Synagogue exist within the maternal embrace of Mary, mother of Christ.

Below the stained glass window, the allegorical figures featuring Ecclesia, Saint George, and the Dragon dominate, a theme ubiquitous in medieval and modern churches. Saint George, the soldier-saint, became a pan-European figure of Christian militancy and triumph over evil. His presence alongside Ecclesia adds a martial dimension to the chapel’s message: the victorious Church is not only allegorical but also militant, a triumph over spiritual and worldly adversaries. The juxtaposition of these figures creates a microcosm of Christian history: the Old and New Covenants, Marian devotion, and the knightly ethos of crusade and protection.

Yet these stained glass windows are not medieval survivals. They are modern creations, shaped by family grief in the 20th century. Their very newness complicates interpretation, for they deliberately echo medieval iconography at a time when such imagery had largely fallen into historical curiosity. Their presence reflects both nostalgia for Gothic grandeur and a desire to anchor modern loss within timeless symbols. To read them as authentic medieval artefacts is a mistake; to read them as modern appropriations of medieval theology is closer to the truth.

Thus, the La Rochefoucauld stained glass became more than decoration. They are a palimpsest of grief, memory, theology, and art. They remind us that Ecclesia and Synagoga are not frozen relics of the Middle Ages but living symbols, constantly reinterpreted according to the needs of new centuries.

Medieval Motif of Synagoga and Ecclesia in Medieval Christian Art: Paul Hildenfinger’s 1903 Study

The deeper story of Ecclesia and Synagoga can only be understood by turning to their medieval roots, and here Paul Hildenfinger’s 1903 study La figure de la synagogue dans l’art du moyen âge remains indispensable. Hildenfinger catalogued their appearances across Gothic Europe, in Strasbourg, Bamberg, Reims, and beyond, demonstrating how they embodied the theological imagination of the age.

He observed that Synagoga is almost always shown with a veil or blindfold (the blindfolded synagogue), sometimes carrying broken “Tablets of the Law” or a shattered lance. Ecclesia, by contrast, is sometimes crowned, holding chalice and Cross, serene and triumphant. Yet, Hildenfinger stressed, Synagoga is not humiliated in these portrayals:

“Les deux religions se regardent sans sympathie; mais l’ancienne conserve sa dignité devant la nouvelle; ce n’est pas une vaincue; rien n’indique sa déchéance.”

English translation: “The two religions regard one another without sympathy; but the older preserves its dignity before the new; it is not vanquished; nothing indicates her debasement.”

This observation is crucial. While medieval polemic often portrayed Jews harshly, the sculpted Synagoga retained dignity, appearing not as a grotesque caricature but as a sorrowful sister. At Reims Cathedral, her features even mirror those of Ecclesia, suggesting familial resemblance. Medieval masons, working with chisel and candlelight, carved a paradox: triumph without complete rejection, blindness without degradation.

Hildenfinger’s insight reveals the complexity of medieval Christian-Jewish relations. While the imagery certainly embodied supersessionist theology (Replacement Theology), the Church succeeding Israel, it also left room for respect and even longing. Synagoga’s blindfold was not only judgment but expectation. Her veiled eyes suggested that revelation was yet to come.

Mary Magdalene or Mary the Magnificat?

In recent years, Thierry Murcia, whose monograph Marie appelée la Magdaléenne: Entre traditions et histoire (Ier–VIIIe siècle) (PUP, 2017), has reshaped the field and demonstrated that the expression usually translated as “Mary Magdalene” does not originally designate a woman from a Galilean fishing village. Drawing on rabbinic, Aramaic and patristic sources, he shows that the word rendered “Magdalene” corresponds in fact to the Aramaic epithet megaddela, “the Magnified”, already applied in Jewish tradition to the mother of Jesus.

The same Semitic root GDL stands behind the first verb of the Magnificat, “my soul magnifies (μεγαλύνει) the Lord”; the “Magdalene” is thus, in Murcia’s reading, Mary the Magnified – Mary of the Magnificat – rather than a woman defined by an obscure locality. In several early strands of tradition, the Mary at the Cross and at the Tomb is therefore the Mother, designated by this honorific title; the later Latin imagination, which turns “Mary Magdalene” into a separate, eroticised figure from Magdala, rests on a toponymic misunderstanding that has overwritten a more ancient Marian memory.

Once this is seen, the medieval pairing of Ecclesia and Synagoga comes into focus. Ecclesia, enthroned with Chalice and Cross, is a corporate image of the Church that easily shades into Marian iconography: Mary the Magnified, Ark of the New Covenant, virgin Bride and Mother-Church carved in stone. Synagoga, veiled and grasping the Tablets, personifies Israel under the Torah – Daughter Zion, Knesset Israel – and in a Jewish mystical key stands nearest to the Shekhinah, the divine Presence dwelling and suffering with her people.

To rebrand Ecclesia as a romanticised “Mary Magdalene” and to detach Synagoga from Torah, Zion and Shekhinah is therefore to erase the original drama between Church and Israel and to replace it with a late Western fiction about a fragmented saint and a free-floating “feminine principle”. For those wishing to know more about the image above showing the Orant (or Orans) posture of Mary, read our dedicated article: Women at the Altar? Myrrhbearers in Early Christian Art and Liturgy

Gothic Cathedrals as Theological Stages: Ecclesia and Synagoga in Strasbourg, Bamberg, Reims, and Paris

The rise of the Gothic cathedral gave Ecclesia and Synagoga their most enduring stage. At Strasbourg, Ecclesia holds a chalice confidently, while Synagoga’s lance slips from her hands. At Bamberg, Synagoga’s blindfold covers her eyes, yet her face retains noble beauty. At Notre-Dame de Paris, Ecclesia and Synagoga flank the portals, greeting the faithful with silent sermons in stone.

These sculptures were not mere decoration. They were theological proclamations made visible to illiterate medieval crowds. In an age before the printing press, stone and glass preached sermons as eloquent as any friar. Ecclesia proclaimed the triumph of the New Covenant; Synagoga embodied the blindness of those who had not yet recognised Christ. Yet their silent pairing reminded viewers that the two covenants were linked, one incomplete without the other.

At Reims, as mentioned, the subtle artistry makes the two figures almost identical. Their resemblance undercuts the triumphalism, hinting that Ecclesia and Synagoga are sisters, not enemies. Theologically, this anticipates Paul’s metaphor of the olive tree in Romans 11, where Gentile branches are grafted onto Israel’s root.

The Gothic drama of Ecclesia and Synagoga is thus both proclamation and paradox. It proclaims Christian triumph while paradoxically acknowledging Jewish dignity. It weaponises imagery in times of tension, yet leaves room for future reconciliation.

Iconographic Attributes of Ecclesia and Synagoga in Medieval Christian Iconography

Throughout medieval and modern representations, the attributes of Ecclesia and Synagoga form a symbolic vocabulary through which theology was made visible in stone and glass.

Ecclesia is almost always enthroned, often crowned as the bride of Christ, and robed in regal garments. In her hands, she carries the chalice, symbol of the Eucharist, and often the cross-staff or banner of victory, recalling the triumph of Christ’s Passion. At times, she bears a sceptre, affirming her sovereignty as the New Covenant, and is frequently placed beneath an architectural canopy or niche recalling the sanctuary of the Church. Her posture is upright, her gaze lifted heavenward, embodying confidence and authority.

Synagoga, by contrast, usually stands veiled or blindfolded, her sight obscured, a continuation of the medieval motif where the Jewish covenant, though dignified, is marked by blindness to the messiahship of Christ. In her hands, she holds the Tablets of the Law, often slipping or inverted, and sometimes a broken spear or banner, signifying defeat. Her crown may be tilted or fallen, her body bent slightly downward, not in humiliation but in sorrow.

As Paul Hildenfinger observed, Synagoga “conserve sa dignité devant la nouvelle [alliance]; ce n’est pas une vaincue” (La figure de la synagogue, 1903, p. 27). Her dignity remains intact, even as she represents a covenant awaiting fulfilment.

These attributes were not casual artistic inventions but theological codifications: Ecclesia as the triumphant Church, bearer of sacrament and grace; Synagoga as the elder sister, momentarily veiled, still guarding the “Law” but awaiting its unveiling. Their juxtaposition in portals and chapels offered worshippers a visual catechism of history, prophecy, and eschatological hope.

From Veil Theology to Anti-Judaism: Historical Consequences of Ecclesia and Synagoga Imagery

Despite their nuance in stone, the allegories of Ecclesia and Synagoga were often weaponised in medieval thought. Preachers like Peter the Venerable used Synagoga’s blindness to argue for Jewish rejection by God, fuelling anti-Jewish sentiment. This “veil theology” migrated from sculpture to sermon, transforming symbolic art into social reality.

Thomas Aquinas offered a more theological interpretation: Synagoga’s veil symbolised spiritual blindness, not moral fault. For Aquinas, Jews remained beloved of God, their blindness temporary until the final revelation. Yet even this charitable interpretation, in practice, reinforced Jewish marginalisation. The veil became not only a metaphor but a justification for exclusion from civic life.

By the later Middle Ages, popular piety often distorted Synagoga into caricature. Sermons at Passion plays depicted Jews as Christ-killers, reinforcing hostility. The dignity carved into cathedral portals was lost in popular imagination. What began as a subtle allegory devolved into fuel for pogroms, ghettos and antisemitism.

Thus, Ecclesia and Synagoga embody a tragic duality: theology intended as mystery became justification for violence. Stone that once whispered of dignity was heard by crowds as a cry of triumph over a despised neighbour. For a free PDF about Ecclesia and Synagoga imagery and Jews and Anti-Jewish Fantasies in Christian Imagination in the Middle Ages, “Anti-Jewish Ecclesiastical Propaganda”.

Ecclesia and Synagoga after the Holocaust: Nostra Aetate and Modern Catholic Reinterpretation

In the 20th century, after the horrors of the Holocaust, Ecclesia and Synagoga demanded reinterpretation. The Catholic Church, through the Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate (1965), decisively rejected the doctrine of supersessionism. Judaism, it declared, remained cherished by God, its covenant never revoked. Synagoga’s veil was no longer blindness as judgment, but mystery as waiting.

Modern cathedrals echoed this renewal. At Metz, artists created new windows where Ecclesia and Synagoga stand unveiled, equal in dignity, both gazing toward the future. In Freiburg, modern sculpture reshaped Synagoga not as defeated but as contemplative, in dialogue with her sister. Art and theology together sought to heal centuries of division.

Theologians, too, reframed the sisters. Dom Nicholas Oehmen (Benedictine monk of Chevetogne) argued that the original schism between Synagogue and Church is the root of all later Christian divisions. Healing this rupture, he suggested, belongs to the eschatological fulfilment when Israel and the Church are reunited. His vision, echoing Paul in Romans 11, transforms Ecclesia and Synagoga from symbols of division into harbingers of final reconciliation.

Thus, the veiled sister rises again in modern imagination, not as defeated but as expectant, her dignity restored, her role reinterpreted in a triumph of Christianity.

Roman Catholic Teaching and Mystical Readings of Ecclesia and Synagoga: Bride, Sophia, and the Shekhinah

Beyond theology and history, mystics glimpsed deeper meanings in these figures. Hildegard of Bingen saw the Church as a radiant Bride, but she also evoked the lingering presence of Israel’s wisdom. Later mystics like Jakob Böhme spoke of Sophia, divine wisdom hidden yet present, veiled yet luminous; a figure not unlike Synagoga waiting for fulfilment.

In Jewish mysticism, the Shekhinah, the divine presence in exile, resonates with Synagoga’s veiled form. In Christian mysticism, Ecclesia as Bride parallels this imagery. Together, they suggest that Ecclesia and Synagoga are not two separate women but two faces of the same Bride; Law and Grace, hidden and revealed, exile and fulfilment.

This mystical reading transforms the sisters from rivals into companions, guardians of the divine mystery. Synagoga preserves the Law; Ecclesia proclaims Grace. Without one, the other is incomplete. Their unity reflects the fullness of God’s covenant.

For modern readers, this mystical vision offers a corrective to centuries of polemic. It reminds us that theology’s most profound truths lie not in division but in paradox, not in triumph but in communion.

As twilight bathes the ancient stones of Reims Cathedral in amber hues, Ecclesia and Synagoga seem momentarily alive, their carved robes shifting in the play of light. Ecclesia gazes softly at her sister, not with triumph but with compassion. Synagoga, still veiled, tilts her head ever so slightly, as if preparing to see.

The veil trembles; not in sorrow, but in expectation. The recognition long foretold is near, though not yet complete. For Christians today, these sisters symbolise a sacred kinship: memory and hope, Law and grace, promise and fulfilment. The Church cannot forget her Jewish roots; Israel cannot be erased from God’s covenantal plan.

In their eternal vigil, Ecclesia and Synagoga challenge both faiths to humility. They remind Christianity that triumph divorced from its Jewish sister is empty, and they remind Judaism that its witness endures within God’s mysterious design. Together, they embody a truth best glimpsed not in isolation but in a shared pilgrimage toward the divine horizon and a covenant with God.

The veiled sisters of the covenant still whisper through stone and glass. Their voices call us to remembrance, reconciliation, and reverence for the mystery of God’s unfolding revelation. Feminist or not, women and men alike must finally acknowledge Mary the Magnificat – not only as Ecclesia in our time or Mother of the new Church, grafted from the old Torah and Synagogue, but also as a living icon of the divine Shekhinah. Mary becomes Church and Synagogue.

Selected Bibliography on Ecclesia and Synagoga, Jewish–Christian Relations, and Medieval Christian Art

- Hildenfinger, Paul. La figure de la synagogue dans l’art du moyen âge. Paris, 1903.

- Murcia Thierry, Marie appelée la Magdaléenne: Entre traditions et histoire (Ier–VIIIe siècle) Presses universitaires de Provence, 2017.

- Vatican II. Nostra Aetate. 1965.

- Oehmen, Nicholas. Le schisme dans le cadre de l’économie divine. Irenikon, vol. 21, 1948, pp. 6-31.

- Rota, Olivier, ed. Histoire et théologie des relations judéo-chrétiennes: un éclairage croisé. Parole et Silence, 2014.