Jesus Christ was Married to Mary Magdalene? A Da Vinci Code Revelation Awaits! An Ancient Manuscript Hides a Triple Chiasma.

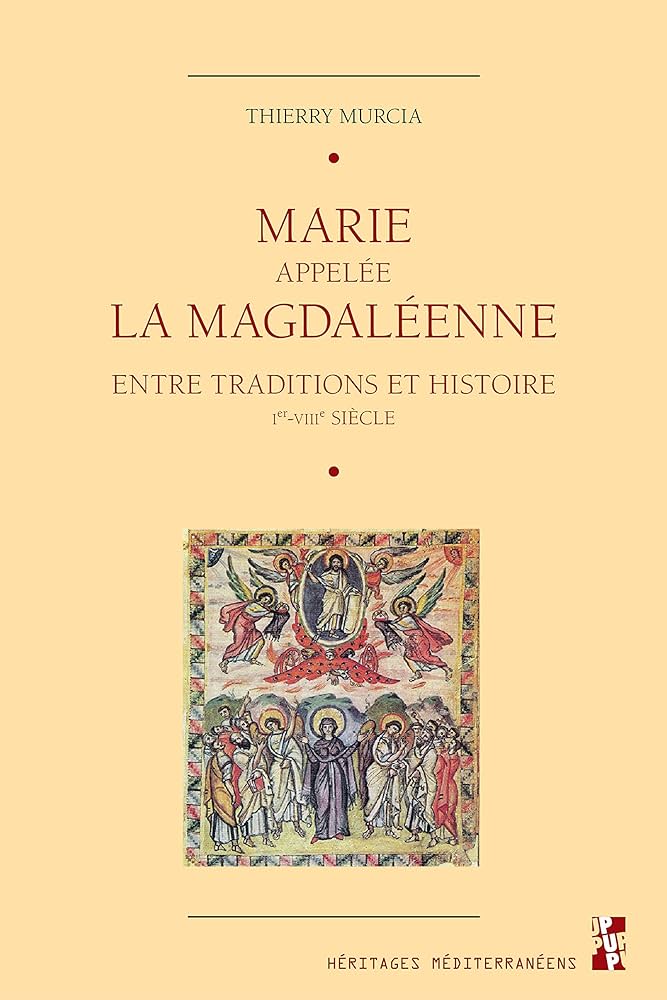

Amid religious and historical texts regarding Mary, a secret is waiting to be unveiled – The Mary Magdalene Code. The revelation that Jesus had a wife is not a new theory. However, Doctor of History Thierry Murcia, PhD., brings forth an entirely new understanding of Mary via his Peer-reviewed thesis. Available in book form, Marie appelée la Magdaléenne: Entre traditions et histoire. Ier – VIIIe siècle, Aix-en-Provence, Presses universitaires de Provence, coll. « Héritages méditerranéens », 2017.

The Triple Chiasma

The groundbreaking discovery of a triple Chiasma by Thierry Murcia has initiated fervent debates, challenged beliefs, and reshaped many people’s perceptions of Mary Magdalene. In this article, we embark on a journey to explore the enigmatic world surrounding ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and the astonishing revelation of Jesus’ wife.

To truly understand the significance of this revelation, it is essential to give our readers a little background and historical context that surrounded Mary Magdalene during biblical times. Often portrayed with misunderstood connotations in popular culture, we aim to highlight her proper role and importance within early Christianity.

By unraveling misconceptions and addressing common myths associated with Mary Magdalene, we hope to present a more accurate representation of her character. Not the mythological figure in non-historical renderings.

Scholars such as Thierry Murcia have revealed more information concealed through meticulous examination of ancient biblical texts. By exploring these revelations, we can also delve deeper into understanding their beliefs and shed light on previously unseen aspects of their spirituality.

The Gospel of Jesus

As we embark on this exploration, we must recognize the skepticism and criticism that inevitably surround controversial discoveries such as ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’. The doubts raised challenge our understanding of history and religion, causing us to question long-held beliefs about Christianity’s foundations. We aim to examine these debates objectively while considering their implications for faith and gender equality. There is also the Sophia of Jesus Christ, sometimes titled the Wisdom of Jesus Christ; we won’t include this Gnostic text in this article, although it features in magazine articles and a future book regarding Mary.

In essence, The Revelation of Jesus’ Wife brings forward intriguing questions about our past while simultaneously provoking thought about its potential impact on modern society. As we reflect on the importance of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and its contribution to our understanding of history and spirituality, we recognize its continued relevance today.

The legacy of Mary Magdalene remains influential, as her story continues to inspire discussions on gender equality and the role of women in religious narratives. Join us on this enlightening journey as we explore the mysteries within ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and grasp its profound significance.

The Significance of The Mary Magdalene Code

One of the significant implications of this revelation is its potential impact on the perception of women in Christianity. Throughout history, women’s roles within the church have often been limited, with interpretations of biblical texts reinforcing male-dominated leadership. The mention of a wife for Jesus in this text suggests that there were women who played important roles within the early Christian community and challenged the idea that all disciples were male.

This revelation also sparks a conversation about gender equality within the context of religious leadership. If Jesus was indeed married, it raises questions about why this aspect of his life was omitted from traditional narratives. Does it suggest that women had more prominent roles in shaping early Christian beliefs? Does it challenge the idea that only celibate men can have spiritual authority?

These questions bring attention to important issues surrounding gender equality not just within Christianity but also within religious institutions as a whole. Highlighting the existence and potential significance that early Christians believed that Jesus married Mary Magdalene prompts us to reevaluate long-held beliefs and consider how they may have been influenced by societal norms rather than historical accuracy.

Controversial New Text About Jesus and The Mary Magdalene Code

Many of our readers claim that Jesus had a wife; however, there is no evidence of a historical Jesus being married nor a reference to having a wife. The controversy surrounding Thierry Murcia’s revelation of his discovery of a triple Chiasma in the Gospel of John has been immense. Even within some circles, many have tried to suppress his findings. These people refute his claims without understanding the languages used within the Gospels. They also tried to undermine the expertise of scholars of the ancient Greek language, disputing and disrespecting Dr. Murcia’s peer-reviewed thesis. Thankfully, the truth is gaining ground in the English-speaking world thanks to dedicated followers. We hope this article on Templarkey will bring its readers an understanding of this never-before hidden code of the triple Chiasma, the limelight it deserves, and ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ becoming freely accessible to everyone.

Mary Magdalene the Discovery

‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ has captivated the attention of scholars and enthusiasts alike, sparking intrigue and fascination. At the heart of this mystery lies the discovery of an exceptional code hidden within ancient biblical texts that shed light on the enigmatic figure of Mary Magdalene. The following sections will delve into the fascinating process of unearthing these historical treasures, revealing a long-forgotten world.

Excavations in Egypt and Early Christians

Egypt is one of the key locations where these ancient texts and artifacts related to ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ have been found. Over the years, numerous archaeological excavations have taken place, unearthing fragments of papyrus with inscriptions that provide valuable insights into the life and teachings associated with Mary Magdalene. These discoveries have allowed historians and researchers a glimpse into an era when early Christian communities flourished.

The Nag Hammadi Library

The Nag Hammadi Library has proven to be one of the essential sources for unraveling the secrets behind ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’. Discovered by chance in 1945 by an Egyptian farmer named Muhammad Ali al-Samman, this treasure trove includes thirteen ancient codices containing Gnostic texts, such as a fragment of the Gospel of John (Apocryphon of John) and some of which prominently mention Mary Magdalene. These texts shed light on alternative interpretations of Christianity prevalent during this period.

The Karen King Ancient Manuscript Hoax

Jesus was married to Mary, according to Fantastic Realism authors such as Dan Brown. This idea gained even more popularity after discovering a Coptic papyrus fragment of the so-called ‘Gospel of Jesus’ Wife’ in 2012. The fragment contained a phrase that translated to “Jesus said to them, My wife.”

However, scholars quickly pointed out that this fragment had not been authenticated and could be a modern forgery. You can see the book Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, written by Ariel Sabar, and an article on CWR by Angela Franks, Ph.D.

Owner of the Papyrus

Dr. Karen L King (Harvard Divinity School) follows an alternate Christianity centered around a sexualized Mary Magdalene. She is famous for promoting a scrap of papyrus she acquired from Walter Fritz. The title ‘The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife’ was given to the fragment by King. Fritz studied Coptic, the language in which the papyrus is composed, at the Free University and was the director of the Stasi Museum in Berlin, East Germany. After leaving his job, he moved to Florida, where he ran successful pornography websites featuring his wife, who claimed to receive divinely inspired sayings by channeling God and Michael the Archangel, which she compiled into a book. For many scholars, Fritz more than likely forged the Gospel himself.

Fritz supposedly acquired the papyrus from a German-American collector who had acquired it in the 1960s in East Germany. Although many believed the papyrus was a fake, King refused testing before going public at the academic conference in Rome in 2012. The Gospel of Judas underwent laboratory testing before being announced in 2006, which is customary for blockbuster manuscript finds. In contrast, laboratory testing was omitted for the manuscript in question. After an investigative article by Ariel Sabar, published online in June 2016 by The Atlantic, King acknowledged that the papyrus was a forgery. There is no historical evidence to suggest that Jesus and Mary were married.

For those wishing to read more regarding the forged Gospel deployed by Karen King, we recommend A Lycopolitan Forgery of John’s Gospel by Christian Askeland. You can also read Ariel Shisha-Halevy, ‘Sahidic’, in The Coptic Encyclopedia (1991), 194–202, at 194–5. Also, see Dr. Thierry Murcia’s The (pseudo) Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.

The Coptic John fragment was clearly copied from Herbert Thompson’s 1924 publication of the Lycopolitan Qau codex and shared the same hand, ink, and writing instrument with the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife fragment.

The Historical Context

To fully understand the significance of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code,’ it is essential to delve into the historical context surrounding the life and role of Mary Magdalene during biblical times. Mary Magdalene was a prominent figure in the New Testament, particularly concerning Jesus Christ. She is mentioned in various gospel accounts and is often depicted as one of Jesus’ most faithful followers. However, her exact role within Jesus’ inner circle is a subject of debate among scholars.

According to biblical accounts, Mary Magdalene was present at critical moments in Jesus’ life, including his crucifixion and resurrection. She was one of the first witnesses to encounter the risen Christ. This has led many to believe that she played a significant role in spreading the teachings of Jesus and establishing early Christian communities.

Despite her essential role within early Christianity, Mary Magdalene has also been the subject of misconceptions and misunderstandings throughout history. For centuries, she was wrongly identified as a repentant prostitute based on a conflation with other biblical characters. However, there is no biblical evidence to support this interpretation. It is essential to dispel the notion that Mary Magdalene was a lesser disciple than the male disciples. While it is true that she often receives less attention in biblical narratives, it does not diminish her significance. She played a crucial role as one of Jesus’ closest followers and remained faithful even during his crucifixion when many others had abandoned him.

Debunking the Misconceptions

Mary Magdalene is one of biblical history’s most fascinating and controversial figures. Often depicted as a repentant prostitute or a woman of ill repute, she has been shrouded in misconceptions and misunderstandings throughout the centuries. In modern times, it is The da Vinci Code that is mainly responsible for the propagation of the non-historical and fantastical vision of Mary. However, recent research has shed new light on her true identity and role in the life of Jesus. Recent research and scholarship have attempted to dispel these misconceptions and shed light on Mary Magdalene’s true identity and significance. Historians have gained insights into her potential leadership role in early Christianity by studying ancient texts, such as The Gospel of Mary and The Gospel of Philip, and examining archaeological findings related to early Christian communities.

| Key Points | Data |

|---|---|

| Mary Magdalene’s presence at critical moments in Jesus’ life | Prominent follower, witness to crucifixion and resurrection |

| Misconceptions about Mary Magdalene | Wrongly identified as a repentant prostitute, there is no biblical evidence to support this interpretation. |

| Ancient texts and artifacts related to Mary Magdalene’s legacy | The Gospel of Mary, The Gospel of Philip, archaeological findings |

Mary of Magdala the Magnificat

One common myth surrounding Mary Magdalene is that she was a prostitute. This belief stemmed mainly from a sermon by Pope Gregory I in the 6th century, where he equated her with an unnamed sinful woman mentioned in the Gospel of Luke. However, there is no biblical evidence to support this claim. Mary Magdalene is mentioned in all four gospels as a devoted follower of Jesus and one of the witnesses to his crucifixion and resurrection.

Soon afterward, Jesus traveled from one town and village to another, preaching and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. The Twelve were with Him, as well as some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out; Joanna, the wife of Herod’s household manager Chuza, Susanna, and many others. These women were ministering to them out of their means. See Luke 8:3.

The Canticle of Mary the ‘Magnificat’ (Mary’s Song)

Then the Virgin Mary said: “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior! For He has looked with favor on the humble state of His servant. From now on all generations will call me blessed. For the Mighty One has done great things for me.” Luke 1:46-49.

This Canticle of Mary is distilled from a collection of early Jewish-Christian canticles, and all biblical masters agree there are four parts to the Magnificat. The first strophe of the text expresses Mary’s gratitude towards God, while the second praises His power, holiness, and mercy. In the third strophe, Mary draws a comparison between God’s treatment of the proud and the humble.

The fourth strophe recalls the fulfillment of ancient prophecies to the Jews in the form of the Messiah, who at that moment was present in Mary’s womb. The Magnificat is likely based on the Song of Hannah in 1 Samuel. Hannah sang this song to express gratitude to God for her son Samuel. “My heart rejoices in the Lord; my strength is exalted in the Lord. I smile at my enemies because I rejoice in Your salvation” (1 Sam. 2:1).

In the Gospel story, Mary, the mother of Jesus, is not mentioned after the night of the crucifixion when John took her to his home. Then He said to the disciple, “Here is your mother.” So, from that hour, this disciple took her into his home. (John 19: 27); however, in Jewish and Christian legends, Mary Magdalene is believed to have replaced the Virgin Mary as the central figure.

Mary called the Magdalene, and the fictional character Mary Magdalene

The Hellenised version of Mary is ‘Maria’; however, in the Gospel of Matthew, we have a more authentic Hebrew/Aramaic form of her name: Mariam the Magdalene. In the article Missing Magdala and the Name of Mary’ Magdalene’ in Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 146, 3 (2014), 205-223 by Joan E. Taylor, although published previously to the theses by Thierry Murcia, about Mary of Magdala, she gives us her real name.

She is defined as “Maria the Magdalene”, Μαρία ἡ Μαγδαληνή (Mark 15-47; 16. 1, 9). However, in Matthew’s Gospel, her first name is different: she is Mariam the Magdalene, Μαριὰ μ ἡ Μαγδαληνή (Matt 27.56, 61; 28.1), one of several women to witness the Risen Christ.

In the Gospel of John, likewise, she is at the cross and the empty tomb and is first to see the resurrected Jesus (John 19.25; 20.1, 11-18); she is named in John as she is in the Gospel of Mark as Μαρία ἡ Μαγδαληνή, but when Jesus addresses her directly he calls her Mariam (Μαριὰμ).

The name “Mariam” appears to preserve the original Aramaic or Hebrew (Ἑβραϊστί), as also her address to Jesus as “Rabbouni” (Ραββουνι), ‘my great one/sir’, translated in John as ‘Teacher’ (John 20.16), meaning that she was a disciple of Jesus. In using the name Mariam, Matthew is then consistently reflecting a more authentic Aramaic/Hebrew form of her name rather than the Hellenised ‘Maria’ (cf. Rom 6.6).

In a paper published in 2022, Elizabeth Schrader (Ph.D. candidate at Duke University) and Joan Taylor (professor at King’s College, London) challenge the assumption that Mary’s place of origin is Magdala, arguing that it is entirely speculative. Read the article Was Mary Magdalene really from Magdala? Two scholars examine the evidence by Yonat Shimron.

Instead, they say, Magdalene may be an honorific from the Hebrew and Aramaic roots for ‘tower’ or ‘magnified’. Just as the Apostle Peter is given the epithet ‘rock’ (“You are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my Church”), Mary could well have acquired the title ‘Magdalene’ meaning “tower of faith,” or “Mary the magnified.”

Paul Anton De Lagarde (1827-1891)

Lagarde proposed that Mary Magdalene’s name was not linked to a mythical town called Magdala but connected to the Hebrew word Magdila’ya, ‘the hair-plaiter’ derived from magdila, ‘braider’ from gadal, ‘to plait or twist’.

Marie appelée la Magdaléenne by Thierry Murcia

The central thesis of Thierry Murcia’s Marie appelée la Magdaléenne: Entre traditions et Histoire: Ier-VIIIe siècle, can be summarized as follows: Mary Magdalene is the mother of Jesus. According to Nicolas Asselin, “The work is well structured and documented; the author begins by deconstructing the myth of Mary Magdalene, the sinner, recalling the Latin origin of the myth, created in the 6th century by Gregory the Great (p. 28).”

Nicolas Asselin concludes that “Thierry Murcia’s demonstration is well-argued; there is no doubt that it highlights the fact that Μαγδαληνή has nothing to do with an adjective relating to a place but that it is the nickname of the character or an adjective linked to Marie.” Nicolas Asselin in the article Littérature et histoire du christianisme ancien.

The following text is from Thierry Murcia (see his Academia site for many of his PDFs).

According to Luke, who relates the episode, Mary visited her relative Elizabeth shortly after the Annunciation. The latter, older than her, is pregnant with John the Baptist. Elizabeth blesses her relative, who responds by singing a hymn known as the Magnificat (Luke 1, 46-55). This name (Latin) comes from the first word (incipit). From the Latin translation of this song of praise: Magnificat anima mea Dominum, that is: “My soul magnifies the Lord” (Luke 1, 46). The Greek text bears: Μεγαλύνει ἡ ψυχή μου τὸν Κύριον.

Although the Gospels were written in Greek (then translated into Latin), Mary – whether the episode is historical or not – is supposed to have spoken in Hebrew or Aramaic. In Hebrew, as in Aramaic, the first word of the hymn – Μεγαλύνει in Greek, Magnificat in Latin – is built from the root GDL (גדל), just like the Aramaic epithet Megaddela (מגדלא), which means ‘the Magnified’ and which refers to the mother of Jesus. In Hebrew, the first words of the Magnificat – “My soul magnifies the Lord (YHWH)” – can be translated as:

Magdilah nafshi et YHWH (מגדילה נפשי את יהוה).

Hebrew Magdilah corresponds here to Latin Magnificat.

The Gospel of Mark Mary/Marie/Mariam Magdalene Mother of Christ

Mark 15:40-41

The Crucifixion

“And there were also women watching from a distance. Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary, the mother of James the Younger and of Joses, and Salome. These women had followed Jesus and ministered to Him while He was in Galilee, and there were many other women who had come up to Jerusalem with Him.”

- Mary/Maria Magdalene,

- Mary/Maria, the mother of James the minor and of Joseph

- Salome

Mark 15:46-47

The Burial

“So Joseph bought a linen cloth, took down the body of Jesus, wrapped it in the cloth, and placed it in a tomb that had been cut out of the rock. Then, he rolled a stone against the entrance to the tomb. Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of Joseph, saw where His body was placed.”

- Mary Magdalene

- Mary, the mother of James/Jacob the Minor and of Joseph (Joses).

Mark 16:1

Pre Resurrection

“When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so they could go and anoint the body of Jesus.”

The Multiple Marys and Robert Ambelain

There are two choices: who was the mother of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark; the first is that the mother of Jesus was not present. The second choice for the mother of Jesus would be the mother of James the Younger and of Joseph/Joses.

Robert Ambelain states: “We can also understand very well the reason for the total silence of the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles, the stories of Papias, and Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius of Caesarea, a huge work composed at the time of Diocletian because all ignore Mary of Magdala.”

He continues: “The reason is that she is confused with Mary, the mother of Jesus, the descendant of David by her second Woman, Bathsheba (ex-wife of Uriah the Hittite), who is also of the Davidic and royal race. As such, she can be called David’s Tower and the mother of the seven thunders, the main of them being Jesus.”

He concludes: “From these contradictory statements, we can conclude that his mother is necessarily the one who constantly returns without any possible ambiguity. And Salome being excluded, it can only be ‘Mary of Magdala’ or ‘Mary mother of James and Joseph’ (alias Joses), or the mother of the sons of Zebedee.

However, all these verses emphasize that it is the mother of several children and not their mother-in-law unless it is only one woman. In any case, the perpetual virginity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is thus excluded; it falls, this virginity, from the myth and popular legend.” Jesus Ou Le Mortel Secret Des Templiers, Collection Les enigmes de l’univers, Editions Robert Laffont, 1970, by Robert Ambelain page 144-145.

Robert Ambelain fails to give an accurate conclusion due to his theory of Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of James the Minor and Joseph/Joses. Mary (mother of James/Jacob the Minor/lesser and Joseph/Joses) was, in fact, the wife of Cleophas; therefore, only Mary the Magdalene could be Mary the Mother of Jesus. Furthermore, in his book, Robert Ambelain only mentions Daniel Massé in passing; however, Ambelain’s theories came directly from Massé. According to the theory by Daniel Massé and Robert Ambelain, Salome would, therefore, be the beloved of Jesus due to her being present at the Crucifixion. Through logic, if a beloved of Jesus were present at the Crucifixion, she would be Salome, as Daniel Massé and Robert Ambelain suggested. Thus, Mary, the mother of James the Minor, and Joseph/Joses would be the Aunt of Jesus, and Mary the Magdalene would logically be the mother of Jesus.

According to Gino Sandri in the article on the website Le Philosophe Inconnu, “Robert Ambelain takes up the theses of Daniel Massé, which can be found in L’Enigme de Jésus-Christ: Le Christ sous Tibère et le Dieu de Jésus, 1926, Editions Du Siècle.” Also, according to the publishing house Arqa, “Robert Ambelain entirely salvaged the theses of Daniel Massé in the 1970s, to be used in the writing of Jesus Ou Le Mortel Secret Des Templiers; La vie secrète de Saint Paul and Les lourds secrets du Golgotha.”

The myths of Jesus and Mary in France (especially linked to Rennes-le-Château) having children (Desposyni) were propagated in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail by Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent, and Richard Leigh and not by Pierre Plantard. There are two other articles linked with Mary Magdalene in France: Cultus of Mary Magdalene, Sara & Jesus, The 1st Sacred Pilgrimage, and Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Saint Sara La Kali The Rare. In The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail by Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent, and Richard Leigh, they include their theory regarding Mary Magdalene as the Woman with the Alabasta Jar and Mary of Bethany coming to France, which is based on the Provençal legend implemented by the Roman Catholic Pope. The second part of their theory of the marriage between Jesus and Mary is the secret Cathar tradition by Father Donden. These two traditions are expanded and explained in our articles above and Issue 9 [October 2023] of The Quarterly Templarkey Magazine (Cathar Special Edition) in the article ‘Jesus, Mary Magdalene and the Cathars’ [Part one], with [Part Two] in January 2024.

The Gospel of Matthew Mary/Marie/Mariam Magdalene Mother of Christ

Matthew 27:56

The Crucifixion

“Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of Zebedee’s sons.”

Different women are looking at the Crucifixion:

- Mary/Mariam Magdalene,

- Mary/Maria, the mother of James the minor and of Joseph

- Mary Salome, the mother of Zebedee’s sons (James/Jacob the Major and John the Apostle.

In the Gospel, according to Matthew, there is the mother of Zebedee’s sons (James/Jacob the Major and John the Apostle); however, writers such as Daniel Massé and Robert Ambelain’s theory have Salome as the beloved of Jesus would have been a child lover of Jesus because she was roughly 12 years old. Their Salome was the daughter of Herod II and Herodiade, the child dancer present at the beheading of John the Baptist.

Matthew 27:61

The Burial

“Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were sitting there opposite the tomb.”

Matthew 28:1

Pre Resurrection

“After the Sabbath, at dawn on the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to see the tomb.”

The Inside Story & the Gospels

One of the most fascinating aspects of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and The Revelation of Jesus’ Wife is the need to continue decoding the complicated structures within the biblical texts. These ancient documents contain a wealth of hidden meanings and messages that are key to unlocking a deeper understanding of Mary Magdalene’s role in biblical times.

Artistic Depictions

In addition to textual evidence, various artistic depictions have contributed to our understanding of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’. Ancient paintings, sculptures, and other forms of artwork showcase different aspects of Mary Magdalene’s life and role within early Christian communities. These visual representations provide valuable context and insights into how her contemporaries perceived her. The discovery of the ancient Chiasma relating to ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ offers a unique opportunity to bridge gaps in our knowledge about biblical times. As we delve deeper into history through excavation and analysis, we uncover a rich tapestry of stories and beliefs that challenge conventional narratives.

Thierry Murcia’s finding of the triple Chiasma is crucial for several reasons. First, it allows us to gain insight into the thoughts, beliefs, and teachings of Mary Magdalene herself. By unraveling these hidden messages, we can uncover her unique perspective on spirituality, womanhood, and her relationship with Jesus.

Furthermore, it helps us to understand the broader context in which Mary the Magdalene played a pivotal role within Christianity, providing valuable information about the cultural, social, and religious milieu of biblical times. Therefore, shedding light on how certain women were perceived and treated during that era challenges traditional narratives that have marginalized or overlooked their contributions.

Revealing Hidden Meanings

As each layer of meaning unfolds through ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’, we gain a richer understanding of the messages conveyed within the texts. These unique Chiastic structures often have a Gnostic sense and touch on themes many experts will continue to study and try to understand for many years.

Through her teachings and journey alongside Jesus, Mary the Magdalene challenges traditional gender roles and offers a different perspective on spirituality. Her character represents a powerful force for women’s liberation, emphasizing the importance of inner strength, resilience, and an equal partnership with men.

Decoding the Chiastic structure also provides insight into Mary Magdalene’s relationship with Jesus. The hidden messages suggest a deep spiritual connection transcending traditional interpretations of their bond. Understanding this aspect can shed new light on Jesus’ teachings and his role as a catalyst for spiritual awakening.

The Controversy

Since its discovery, ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ has not been immune to skepticism and criticism. While some have embraced the revelations it presents, others have raised doubts about its authenticity and validity. This section will delve into the controversies surrounding the code and examine the various criticisms. As debates continue to unfold, it is essential to approach discussions surrounding ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ openly, acknowledging both sides of the controversy. Only through rigorous research and scholarly debate can we hope to gain a clearer understanding of the significance of the triple Chiasma found by Thierry Murcia.

The Relevance Today

One of the most intriguing aspects of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and the Revelation of Jesus’ Wife is the continued influence of Mary Magdalene’s legacy in modern society. Despite being a figure from biblical times, Mary Magdalene’s impact can still be felt today in various aspects of our lives. This section will delve into the relevance of her legacy and how it continues to shape and inspire individuals and communities.

Firstly, one cannot ignore the significant role that Mary Magdalene plays in feminist theology and women’s empowerment. Throughout history, women have often been marginalized and their voices silenced. However, Mary Magdalene’s portrayal as a strong and independent disciple challenges traditional gender roles and serves as a symbol of female empowerment. Her presence offers a counter-narrative to the patriarchal structures that have dominated religious institutions for centuries.

Furthermore, Mary Magdalene’s story resonates with individuals who seek spiritual enlightenment outside conventional religious frameworks. Many seek alternative forms of spirituality that emphasize personal connections with the divine rather than hierarchical structures. Mary Magdalene, with her close relationship towards Jesus beyond that of a mother/son relationship and her deep understanding of his teachings, represents a spiritual path that focuses on love, compassion, and inner transformation.

Lastly, Mary Magdalene’s legacy reflects society’s quest for historical truth and authenticity. The discovery of the triple Chiasma has sparked intense curiosity among scholars and enthusiasts alike. People are drawn to uncovering hidden knowledge about our past, especially when it challenges established narratives. The research surrounding Mary Magdalene provokes essential questions about how history is constructed and whose stories are deemed worthy of preservation.

‘The Mary Magdalene Code’

In conclusion, the unveiling of ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ and the Revelation of Jesus’ Wife hold immense significance in our understanding of history and spirituality. Through a detailed exploration of the historical context and debunking common misconceptions, we have gained valuable insights into the real life and role of Mary in biblical times. The discovery of the triple Chiasma has given us a rare opportunity to delve deeper into this mysterious figure.

By exploring Mary Magdalene’s legacy and continued influence in modern society, we acknowledge her relevance today as an icon of strength, resilience, and spiritual transformation. We have no evidence Christians believed Jesus was married; however, we now have a Mary whom Jesus could say was “able to be my disciple.”

Ultimately, ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ contributes to our understanding of history by unveiling previously hidden narratives that challenge existing beliefs. It invites us to question widely accepted interpretations while encouraging a more nuanced appreciation for spirituality beyond traditional boundaries. Reflecting on this journey, we must embrace diverse perspectives to deepen our understanding of history and spirituality.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Symbol for Mary Magdalene?

The symbol for Mary Magdalene, following the tradition since the end of the sixth century (implemented by Gregory the Great, 591), varies depending on the context and representation. In Christian art and religious symbolism, Mary Magdalene is often depicted with specific attributes that symbolize her identity. A common symbol of Mary Magdalene is a skull, representing her acknowledgment of mortality and contemplation of death.

What is Mary Magdalene Holding in Her Hands?

In artistic representations, Mary Magdalene is frequently depicted holding a jar or container of precious ointment in her hands. This attribute refers to the biblical account where she anointed Jesus’ feet with expensive perfume as an act of devotion. The jar can also symbolize the repentance and purification associated with Mary Magdalene’s spiritual transformation.

What did Jesus Say About Mary Magdalene?

While there are no direct quotes from Jesus specifically about Mary Magdalene recorded in the Bible, she is mentioned multiple times in association with Jesus’ ministry and crucifixion. In the Gospels, it is stated that Jesus drove seven demons out of Mary Magdalene, and she became one of his followers. She is also mentioned as present during critical moments such as Jesus’ crucifixion, burial, and resurrection.

Why is Mary Magdalene Lilith?

It is incorrect to refer to Mary Magdalene as Lilith. Lilith originates from ancient Jewish mythology and folklore as a figure associated with darkness, rebellion, and seduction. There is no connection between Mary Magdalene and Lilith in the biblical accounts or traditional Christian teachings. Mary Magdalene is a distinct figure known for her discipleship, faithfulness, and witness to Jesus’ resurrection. Any association between Mary Magdalene and Lilith would result from speculative interpretations or alternative beliefs outside mainstream Christianity.

‘The Mary Magdalene Code’

Mary of Magdala, aka Mary Magdalene, isn’t she the repentant ex-prostitute mentioned by Luke in his gospel (Lk 7:36-50)? The Latin church has affirmed this tradition since the end of the sixth century (Gregory the Great, 591), but the Greek or Syriac churches did not maintain it.

What was Mary Magdalene known for?

Mary Magdalene was known for several reasons within Christian tradition and biblical accounts. She was often identified as one of Jesus’ closest followers and was present during significant moments in his life and ministry. While the sinner in the Gospel of Luke is left anonymous, Mary Magdalene, on the contrary, plays a leading role; she is presented as a privileged witness, and she is also the female character most often cited in the gospels.

Within those who follow Jesus, the Magdalene takes precedence: when she is in the company of other women, she is consistently given precedence. She is present at Calvary and is formally at the head of the women who go to the tomb. And it is she who then fulfills all the duties towards the deceased, which usually fall to the mother.

She played a significant role after his death when she discovered the empty tomb and became one of the first witnesses to his resurrection. In the Gospel of John, it is Mary Magdalene who Jesus appears to on Easter morning.

The Triple Chiasma of John the Evangelist ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’

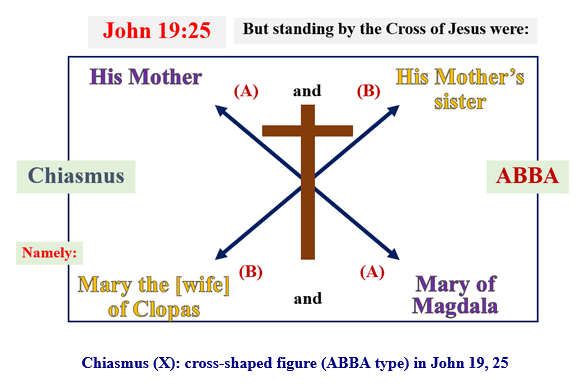

The following and final part of this conclusion is via Doctor of History Thierry Murcia. Let us point out above all that, in the gospels, Mary of Magdala and the mother of Jesus are never present simultaneously, with one exception, it seems, in John 19, 25: “Near the cross of Jesus stood his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary, wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala.”

How Many Women Are at the Foot of the Cross?

Exegetes are still divided on whether the John the Evangelist mentions three or four women here. But, as is often the case, the truth is elsewhere because John only talks about two women here: he presents them and then names them, but in reverse order, because it is a chiasma (classic ABBA-type diagram).

Several commentators (including Raymond E. Brown, not to be confused with Dan Brown) had rightly observed that, in the Gospel of John, the entire story of the crucifixion and burial obeyed a chiasmatic structure, not only on the scale words this time but on the scale of sentences, of ideas – let’s call it: macro-chiasma.

Experts had previously established that this structure revolved around John 19:25-27, which constituted the key and should make it possible to understand the whole thing.

But until then, no one managed to penetrate the code because no one thought of pushing the analysis beyond the macro-structure.

However, it turns out that the three verses of John, located at the heart of the macro-chiasma, also respond, but at the micro-structural level, to a chiasmatic construction, which gives us:

“Near the cross of Jesus stood his mother (A)

And his mother’s sister (B),

Mary, wife of Clopas (B),

And Mary Magdalene (A).

Jesus, therefore, seeing his mother (A)

And the disciple standing near (B),

The one he loved (B),

Said to his mother (A):

“Woman (A),

This is your son (B).”

Then he said to the disciple (B):

“This is your mother (A).” (John 19, 25-27)

In short, the evangelist discreetly inscribes here a series of X-shaped crosses on the † (or T-shaped) Cross on which Jesus is tortured. Let us specify that this particular construction is justified in this Gospel, but we will not go into details here. The rest of the story is known: Mary Magdalene then goes to the tomb where Jesus appears to her. John’s story is, therefore, very coherent: just as his mother is present at the Cross, she is also present at the tomb.

According to the traditional reading of evangelical sources, Mary, the mother of Jesus, although present during the public ministry of her son (Mt 12, 46-50; 13, 55; Mk 3, 31-35; 6, 3; Lc 8, 19-21; Jn 2, 1-12) would indeed have been absent, both during the Passion (except in John), the burial, and the visit to the tomb. But with this new light, we see this is not the case. She never stopped being present.

Suppose we compare the lists of women present during the Passion, which appear in the Synoptic Gospels (which seemed to ignore the presence of Jesus’ mother) with that of John. We then see they are no longer irreconcilable (this appears to be the case so far).

Mark (Mk 15:40) and Matthew (Mt 27:56) mention three women: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the Minor, and Joses – whom Matthew also calls ‘the other Mary’ (Mt 27:61; 28). , 1) – as well as Salome (the mother of two apostles, James and John). Indeed, the group spoken of in the Synoptics still includes other women they do not name. These, it is specified, stand at a distance and observe from afar. We are in external focus. In Jean, the perspective changes: the focus is internal, and the scene is seen up close.

This time, there are only two women: the mother (Mary of Magdala) and the aunt of Jesus (the other Mary, in reference to the previous one); in other words, close relatives. There is a change of point of view. For what? Let us quickly say that Mark and Matthew echo the ‘apostolic tradition’, while John, who excludes Salome from the circle of intimates, reflects the ‘family tradition’ here.

What do Ancient Sources say?

But how is it, if this reading is accurate, that no ancient source has preserved traces of it? In reality, and even if it may seem incredible, the sources exist and are numerous.

Before the Latin tradition made Mary Magdalene a former prostitute, the much older Syriac tradition had identified her with the mother of Jesus. And Ephrem of Nisibis is far from being the only representative of this tradition. We also find traces of it in numerous other ecclesiastical writers (Syriac, Coptic, Greek, and even Latin), the Apocrypha, Gnostic or similar writings, and even the Babylonian Talmud.

As such, the heated debate has agitated specialists for years around the identity of the ‘Mary’ of Gnostic texts – Mary, the mother of Jesus, or Mary Magdalene? – is ultimately ridiculous because it is pointless. Once is not customary, everyone is correct since it is in reality, as in the gospels, the same character, sometimes called ‘Mary’ and sometimes ‘Mary the Magdalene’ or of Magdala, but has anyone ever had the idea of wanting to distinguish, in the gospels, ‘Jesus’, ‘Jesus the Nazarene’ or ‘Jesus of Nazareth’.

Note this carefully: in these documents, the two Marys are never present simultaneously (take the Pistis Sophia, for example), simply because they cannot! Wanting to distinguish them at all costs amounts to nothing more, nothing less, to arguing over whether it is instead ‘bonnet white’ or ‘white bonnet’ (thus, a chiasma). And this is valid for all Gnostic or similar texts that have come down to us.

Mary’s Kiss to Jesus

We wanted to make Mary Magdalene the wife or companion of Jesus by relying on these same documents, particularly the Gospel of Mary and the Gospel according to Philip. Mary Magdalene is called the ‘companion’ of Jesus; it is said that Jesus loved her more than any other woman and that he often kissed her on the mouth; the Syriac tradition supports that. As the mother of Jesus, she is also described as a ‘companion’ (in the sense of complementarity, obviously) of her Son, and it is also said that Jesus loved her “more than any other woman.”

“But what is so” surprising for a man who is a priori single and childless to love his mother like this? Especially since filial love is coupled with a mystical love. Leave the kiss on the mouth. Let’s leave aside its symbolic and mystical dimension and get straight to the point: kissing on the mouth was then a widespread practice among friends and relatives, as numerous documents attest.

The daughters embraced their fathers and brothers, and the sons their mothers. Above all, there is a well-established tradition (several texts), but little known at the moment, which is that Mary of Magdala (the mother of Jesus in these stories), at the time of the appearance of her Son, wanted to kiss her on the mouth: an eminently natural act on the part of a mother, especially given the circumstances.

Here is how it is reported by the pseudo-Cyril of Jerusalem (a text which has come down to us in Coptic – like most Gnostic writings:

« “He said to her: “Mariham.” She recognized that it was her Son and wanted to kiss him, exclaiming in Hebrew: “Rabboni,” which translates to Master. She ran to meet him, eager, in her joy, to embrace him and kiss his mouth – since no human being would be capable of curbing his joy at a moment like this – but he wanted to hold her back and said: “Do not touch me…” »

« And again, from the same author (it is Marie who speaks):

“I was so happy that I approached to kiss him as usual. He said to me: “Do not touch me…” »

Therefore, this is a literary amplification of the episode reported in John (Jn 20, 11-18), of which several variants exist.

The Gnostic writings convey this tradition that I called diatessaric: it was primarily known and transmitted by the authors who used the Diatessaron (through the four), a Syriac harmony of the gospels traditionally attributed to Tatian (around 170), but which is undoubtedly older. But we could, in this case, just as easily speak of ‘family tradition’ since we have seen that it is already present in John: Mary Magdalene is quite simply the complete form of the name of the mother of Jesus. But should we see it as a toponym?

What does Magdala mean?

According to the most widespread explanation, Mary came from the locality of Magdala, on the shores of Lake Tiberias. But this explanation is probably not the right one for several reasons. Here are the two main ones: on the one hand, it was not the custom, at that time and in this environment, to name a woman after her place of origin. On the other hand, and above all, Luke’s use of hê kalouménê (ἡ καλουμένη) between Mary and Magdalene (Μαγδαληνή) appears to exclude any reference to a place name.

Luke writes, in fact (Lk 8:2): Maria hê kalouménê Magdalene (Μαρία ἡ καλουμένη Μαγδαληνή), Mary nicknamed Magdalene. However, in the Bible, when the word kaloumenos (καλούμενος) – in the feminine form in Luke – separates two other terms, and the first of the two terms is a proper name, the second is never a locality name. It is always a nickname that intends to underline a physical or moral characteristic of the character.

If we go back to Aramaic, the term translated as “Mary of Magdala” can have several meanings. They can, in particular, mean Mary, ‘the great’, or even ‘the tower’ (magdela). Or, in Judeo-Aramaic (megaddela): Mary’ the celebrated’, ‘the Magnified’, and ‘the Exalted’ (in the positive sense of the term). It was, therefore, initially a laudatory epithet attributed to Mary, intended to single her out (one in four Jewish women, on average, was called Mary in Palestine at that time) and to underline her eminent character, above all: Luke 1, 42. By designating it thus, the evangelists would have had no reason to be more precise: their first recipients immediately knew who it was about. Once passed into Greek, the meaning of the Semitic term was lost, and it ended up being falsely interpreted as a toponym.

An Unromantic Thesis

This thesis is less romantic and juicy than Dan Brown’s in Da Vinci Code, which is widely supported. It undoubtedly does not respond to the concerns of today’s public, often hungry for sensationalism. There is no need to resort to false papyri to support this theory; thus, rather than being ignored, it would undoubtedly merit further examination. Here is the quickest and least incomplete overview of Thierry Murcias’ findings and ongoing work regarding this issue; his entire thesis is available in French on Amazon, and there is much in English on his Blog.

The Gospel of Phillip

Thierry Murcia follows the translation of Jacques-Étienne Ménard, [Gospel according to Philip 59:6-11, Évangile selon Philippe, Jacques-Étienne Ménard, Paris – Montréal: Lethielleux & Université de Montréal, 1964, p. 79.] which he says remains close to the text and seems to have grasped its spirit:

There were three who always walked with the Lord (ϫⲟⲉⲓⲥ):

Mary (ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ), his mother and her sister, and Magdalene (ⲙⲁⲅⲇⲁⲗⲏⲛⲏ), who is called his companion (ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲟⲥ).

For Mary (ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ) is his sister, his mother, and his companion (ϩⲱⲧⲣⲉ).

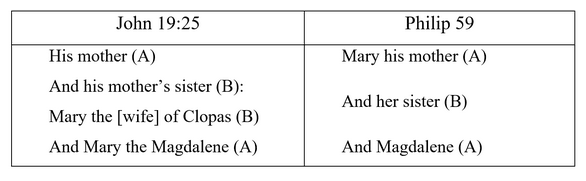

The crucial passage above is made up of three parts. In the first one, three people follow ‘the Lord’. The second part is a rephrasing of John 19:25 (the only passage of the Gospels that attributes a sister to the mother of Jesus and the only one where the Magdalene is named last). In my opinion, the two central elements of the chiasma (B-B) have been merged into one (B), like this:

The above extract is from Thierry Murcia’s article, Mary Magdalene and the Gospel according to Philip, which is a subchapter of a much longer study (about 80 pages) entitled: The Mother of Jesus and the Magdalene: One and the same Mary?

Conclusion

Conclusion

We conclude with the real Mary Magdalene (Mary the ‘Magnificat’). We must thank Doctor of History Thierry Murcia for allowing Templarkey to include his research in this article.

Mary Magdalene as the Mother of Jesus was confirmed through the research by Thierry Murcia, and his discovery of the Tripple Chiasma in the gospel of John 19: 25-27 (‘The Mary Magdalene Code’) matches with the account of the Crucifixion and Ressurection from the Gospels of Mark and Matthew per Eastern orthodox diatessaric tradition. It is why Mary the Mother was designated ‘Magnificat’ (the Magnified) in the Gospel of Luke. Hence, Mary Magdalene is Mary the Mother of Jesus at the resurrection, confirmed by Saint Ephrem’s Commentary on Tatian’s Diatessaron: an English translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709.

Mary Magdalene’s story has been interpreted as a powerful example of redemption, transformation, faithfulness, and devotion. ‘The Mary Magdalene Code’ via Thierry Murcia is now prominent in academia and esoteric circles.