Women at the Altar? Myrrhbearers in Early Christian Art and Liturgy

I am delighted to share that this article forms a crucial chapter in my forthcoming book on the ordination of women in the Christian tradition, an endeavour born of my own experiences as an ordained priest in the historical French Church (H.E.L.I.O.S.) Haute Église Libérale Indépendante Orthodoxe et Syriaque. My goal is to shine a light on the long lineage of female devotion, service, and leadership that has subtly permeated ecclesial life from its earliest roots. This book will integrate deep historical research, personal narrative, and theological reflection to demonstrate that, far from being anomalous, women’s ordination can be understood as a natural outgrowth of the Gospel witness. By weaving these threads together, I hope to offer a resource not merely for scholars, but also for believers everywhere who sense that the Spirit continues to call women to serve as Christ’s ministers in the here and now.

Drawing on my own name, Tau Sophia Christophora—one I took to symbolise the wisdom (Sophia) and Christ-bearing (Christophora) calling placed upon me—I strive to honour those who came before me, especially the myrrh-bearing women, deaconesses, and countless faithful who have enriched the Church’s life. As I compile these articles into a larger, sustained argument, I remain mindful that this book represents part of my doctoral thesis, submitted under my birth name, Sally Elizabeth Jacobs, for the validation of my ordination. My hope is that by illuminating historical precedents and present realities linked to Women at the Altar, we might all more clearly see how women’s ordination speaks not only to tradition and continuity, but also to the Church’s mission of proclaiming the liberating Good News to every generation.

How many Myrrh Bearing women?

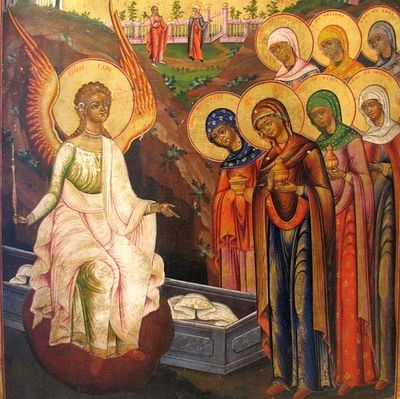

In Christian tradition—especially within the Eastern Orthodox Church—eight women are recognised as the myrrh-bearers, each commemorated for their devotion to Jesus at His crucifixion and Resurrection. These eight figures are Mary Magdalene, Mary the Theotokos (the Virgin Mary), Joanna, Salome, Mary the wife of Cleopas, Susanna, and the sisters Mary of Bethany and Martha of Bethany.

Taken together, they embody the Gospel accounts of those who arrived at the tomb on Easter morning to anoint Christ’s body with spices and ointments. The differences among the four Gospels regarding who came to the tomb, and at what time, likely arise from each evangelist highlighting particular witnesses and moments of discovery. Moreover, the early Church’s oral traditions suggest that the women arrived in various groups and in a staggered timeline, which can account for the slight variations in their stories.

Despite these variations, the Myrrh-bearing women collectively demonstrate profound courage, steadfastness, and love—characteristics that have made them models of faith for centuries. They followed Christ to the cross when most of the disciples had fled, and they were the first to discover the empty tomb, hearing the angelic proclamation of His Resurrection. In liturgical observances—such as the Orthodox Sunday of the Myrrhbearers—their dedication and bravery are honoured, highlighting that women were, from the earliest days of Christianity, at the heart of proclaiming the reality of the risen Christ. Their role as first witnesses underscores the essential part women have played, and continue to play, in the life and testimony of the Church.

Can girls serve at the altar?

Women at the Altar in the Roman Catholic Church:

Historically, serving at the altar was closely tied to the minor orders—offices like acolyte or lector—which, for many centuries, were open only to men and boys. However, during the latter half of the twentieth century, liturgical reforms and the evolving interpretation of canon law sparked discussions on whether to allow girls to serve at Mass. The watershed moment came on 15 March 1994, when the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued an official clarification affirming that:

“Service at the altar is open to both men and women… It belongs, therefore, to the diocesan Bishop to decide whether or not to permit female altar servers in his diocese.”

This 1994 communication underscored two key principles:

- Permission: The universal Church recognised that there was no doctrinal impediment to females serving at the altar.

- Bishop’s Discretion: Each local ordinary (Bishop) held the authority to determine whether girls or women could serve in his particular diocese, considering pastoral needs and local customs.

In practical terms, many dioceses worldwide now allow female altar servers, although the policy remains a matter of episcopal choice. For instance, some bishops introduced the practice soon after 1994, while others waited or chose not to permit it, preferring to preserve the longstanding tradition of male‐only altar servers. Over time, however, it has become increasingly common to see both girls and boys assisting the priest at the altar—vested similarly and performing the same liturgical tasks of carrying the cross, holding the missal for the celebrant, or preparing the altar with sacred vessels.

Some Catholic theologians and pastoral leaders see the inclusion of girls in this ministry as an encouraging step toward fuller lay participation. As Sr. Sara Butler points out in her exploration of ministry and service,

“the faithful—men and women—exercise a common baptismal dignity, even as they accept that ministerial priesthood remains distinct”.

While altar service does not confer ordination, it is often perceived as a formative experience that fosters liturgical knowledge, prayerfulness, and engagement in the community for all who serve.

Women at the Altar in Eastern and Orthodox Churches

In the Eastern Catholic Churches—those in communion with Rome but following Eastern liturgical traditions—practices vary by sui iuris (“of one’s own right”) Church and local episcopal decisions. Some Eastern Catholic eparchies (dioceses) allow girls to assist as servers in a manner similar to the Latin Church, while others maintain a more traditional approach, reserving altar service to boys and men. Since these Churches have their own canon laws and customs, the question of female altar service is handled with sensitivity to each rite’s heritage.

Within the Eastern Orthodox communion, the normative tradition has long been to reserve direct service at the altar—such as assisting the priest or deacon within the sanctuary—to ordained clergy, subdeacons, and sometimes male servers or minor clerics. Consequently, the typical parish has not included girls serving around the altar in a capacity analogous to Latin‐rite altar servers.

However, there are notable historical and modern nuances:

- Ancient Orders: Early texts and liturgical documents suggest that deaconesses (diakonissai) existed in certain Orthodox communities, particularly to assist with women’s baptisms and pastoral care. While their liturgical roles were more restricted than those of male deacons, they often served near or at the altar in a limited capacity, especially in women’s monasteries.

- Contemporary Practice: In recent decades, some Orthodox theologians have discussed the possibility of reinstating deaconesses—not merely as a historical curiosity but as a living expression of the Church’s ministry to women. A few local Orthodox Churches have even ordained women as deaconesses for charitable and catechetical work.

- Choir & Liturgical Participation: Although women typically do not serve inside the sanctuary, they play essential roles in choral singing, chanting, and conducting. In Orthodox worship, the choir or chanters are integral to the liturgy’s prayerful atmosphere. Women may also read the Epistle in certain jurisdictions—albeit usually from the solea (the space just before the iconostasis) rather than within the altar area.

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware observed that in Orthodoxy,

“women’s liturgical involvement outside the sanctuary is both vital and indispensable, though the tradition maintains a strong sense of the priest or deacon’s distinct role at the altar.”

Thus, while the East generally upholds a clear boundary around the altar, it continues to recognise women’s crucial participation in worship—through chanting, teaching, and, in some cases, restoring the ancient order of deaconesses for pastoral service. Although the Roman Catholic Church formally permitted girls to serve at the altar only in 1994, the development reflects broader ecclesiastical shifts toward recognising laypeople’s contributions in liturgical contexts. In the Eastern and Orthodox Churches, the liturgical and historical tapestry is equally rich—rooted in ancient orders and diverse traditions—revealing how women’s ministries at or near the altar continue to evolve within the living heritage of the Church.

Who can be at the altar? Women at the Altar

Altar Servers: A Detailed Summary

Altar servers are laypersons—often children or adolescents, but sometimes adults—who assist the clergy during Christian liturgical services, most prominently in the Roman Catholic Church, but also in Anglican, Lutheran, and some other denominations. Their primary role is to help ensure the Mass or other services proceed smoothly by handling tasks that allow the priest or deacon to focus on the central liturgical actions. Over time, the role of altar servers has evolved, reflecting broader shifts in church law, policy, and pastoral practices.

Historical Background and Terminology

- Minor Orders: Historically, altar service in the Catholic Church was linked to the minor order of acolyte, which was exclusively male. Acolytes were seminary students or those on a clerical track, assisting at the altar as part of their clerical formation.

- Changes After Vatican II: Following reforms of the Second Vatican Council, the practice of having seminarians serve in minor orders diminished in many dioceses, and more laypeople began to assist at the altar. While this allowed greater lay participation, the question of female altar servers remained open for several decades.

Functions and Responsibilities

- Processional Duties: Altar servers often lead the entrance procession by carrying the processional cross or candles. They likewise may help at the end of Mass with the recessional.

- Assisting During Mass: Duties include preparing the altar, holding the missal for the priest, arranging the communion vessels, and sometimes ringing altar bells at key liturgical moments (e.g., during the epiclesis or consecration).

- Handling Incense: If incense is used, an altar server (or thurifer) may prepare the censer (thurible) and assist the celebrant in incensing the altar, gifts, congregation, or sacred images.

Admitting Girls to Serve

- Official Permission: Although boys and men traditionally performed altar service, in 1994, the Congregation for Divine Worship confirmed that bishops could allow girls and women to serve at the altar in the Roman Catholic Church. This official permission recognised that the role of an altar server is distinct from ordination, falling under lay liturgical ministry.

- Local Discretion: Even after permission was granted, each Bishop has the authority to determine local policy. Consequently, some dioceses began integrating female altar servers immediately, while others elected to maintain an all‐male server tradition, citing custom or symbolic considerations.

Altar Servers in Other Traditions

- Anglican and Lutheran Churches: Similar assisting roles exist, often called acolytes or servers. In most provinces of the Anglican Communion and many Lutheran synods, there has been no historical bar against women or girls serving, and the practice of mixed‐gender altar serving is common.

- Eastern Orthodox Churches: Typically, altar service is reserved for males in the Orthodox tradition, often as a minor clerical function. However, some discussions regarding the revival of the ancient female diaconate have prompted limited changes or local experiments. Generally, though, laywomen and girls do not serve within the sanctuary.

Spiritual and Educational Value

- Formational Aspect: For children and adolescents, serving at the altar can foster a deeper understanding of the Mass and encourage a future vocation to ministry—whether lay or ordained. It also teaches responsibility, attentiveness, and reverence for sacred rites.

- Community Involvement: Altar serving is a visible way for laypeople, especially young Catholics, to actively participate in parish life. It can nurture a stronger sense of belonging and engagement with the faith community.

Altar Servers and Their Evolving Role in the Church

In Christian liturgical traditions, altar servers fulfil essential functions by assisting priests or deacons during worship. Historically linked to the minor order of acolyte and reserved for males, this role expanded in the decades after the Second Vatican Council to include more lay involvement. In 1994, the Roman Catholic Church clarified that both boys and girls could serve at the altar while leaving the final decision to each Bishop. Consequently, many dioceses now have mixed‐gender altar server teams that handle tasks such as processing with the cross, holding the missal for the celebrant, preparing the altar, and using incense.

Other traditions, including Anglican and Lutheran communities, have long permitted women and girls to serve without restriction. Meanwhile, in the Eastern Orthodox Churches, strict adherence to custom largely preserves altar service for males, though ongoing discussions about reinstating the female diaconate may prompt broader roles for women. Ultimately, the practice of altar serving underscores lay collaboration in liturgical life, offering educational and spiritual benefits to those who participate.

Myrrhbearers in Early Christian Art and Liturgy

The Myrrhbearers appear in some of the earliest surviving Christian funerary art, where they symbolise both the sorrow of the Passion and the triumph of the Resurrection. On Roman sarcophagi and in catacomb frescoes, these women are occasionally depicted approaching a central figure or shrine, sometimes accompanied by an angel, signifying their intimate role in the Easter mystery.

Early Christian communities, particularly those with a strong devotion to female saints and martyrs, found in the Myrrhbearers a model of steadfast faith. Their willingness to minister to Christ even in the face of death resonated with believers who saw the women’s anointing actions as a bold declaration of love and fidelity—an act at once practical and profoundly theological, foreshadowing the fragrance of new life over the stench of the grave.

The Orant Posture in Early Christian Funerary Art

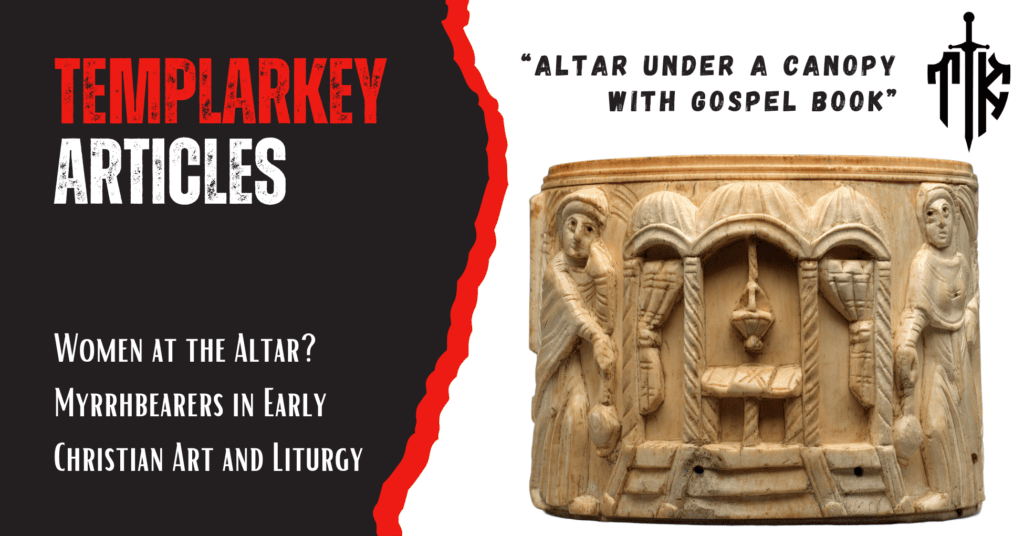

The Orant (or Orans) posture—arms uplifted, elbows slightly bent, and palms facing outward—is a hallmark of early Christian art, symbolising prayer, devotion, and spiritual openness. Far from being restricted to clergy, this stance was widely used in depictions of both men and women, especially in funerary contexts. On the Circular Box (Pyxis) with the Women at Jesus’ Tomb in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, these women are carved in an orant attitude as they approach the tomb, visually emphasizing both their reverent wonder at the Resurrection and their direct communion with God. The pose thus underscores their active engagement in worship rather than a passive, secondary role.

Beyond the small-scale delicacy of the ivory pyxis, the orant figure appears in larger funerary monuments, such as Gallo-Roman sarcophagi housed in the museum at Narbonne. Here, women sculpted in the orant posture often represent the deceased as eternally praying or interceding, testifying to a steadfast faith in the resurrection. This iconography underscores an early Christian conviction that every believer—man or woman—stands before God in prayerful hope. As a result, the orant pose in these artworks functions as a powerful, visual witness to the conviction that resurrection life is available to all, reflecting the tradition’s deep reverence for the faithful departed who now stand perpetually in God’s presence.

Women as Archetypes of Fearless Discipleship

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the significance of these women is further highlighted on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers, celebrated a couple of weeks after Easter. Liturgical hymns and homilies for this day exalt the Myrrhbearers as “apostles to the Apostles” since they were the first to discover the empty tomb and proclaim Christ’s Resurrection. Patristic authors like Ephrem the Syrian and John Chrysostom wrote admiringly of their unwavering devotion, presenting these women as archetypes of fearless discipleship.

In certain monastic communities, readings and hymns stress their blend of practical service (bringing myrrh and spices) and spiritual insight, emphasising that true faith requires both compassionate action and a readiness to receive divine revelation. Their prominence in early art and ongoing commemoration in liturgy affirms that women stood at the very heart of Christian witness, bridging the distance between the crucifixion and the joy of the Resurrection.

Carved onto a small cylindrical ivory box (often called a pyxis), the images of women with censers approaching a domed shrine offer a fascinating window into both the biblical tradition of the Myrrhbearers and the tangible practice of early medieval liturgy in Jerusalem. These women, portrayed with arms raised in the orans gesture, stand before what appears to be the Tomb of Christ, also referred to as the Anastasis (Greek for “Resurrection”), the sacred focal point of Easter celebrations in the Holy City.

The Myrrhbearers in Scripture and Art

According to the Gospel accounts, a group of devout women came to Christ’s tomb at dawn, carrying myrrh and spices to anoint His body (Mark 16:1–2; Luke 24:1–2). Early Christian tradition elevated these “Myrrhbearers” (myrrhophores) as the first human witnesses of the Resurrection. In visual art, they became archetypes of piety and devotion—faithful women acting with both reverence and liturgical solemnity.

On the ivory pyxis, these women’s outstretched arms—though reminiscent of priestly gestures—are best understood as the universal orans posture, widely used in early Christian iconography to depict prayer. In many instances, both men and women saints, martyrs, and ordinary faithful appear in the same pose, emphasising communal prayerfulness rather than clerical exclusivity. Here, the gesture signals the Myrrhbearers’ awe before the empty tomb and their pivotal role as proclaimers of the Resurrection.

The Anastasis Typikon and Liturgical Context

The Codex Stavrou (dated 1122, yet possibly copied from a late ninth- or early tenth-century original) preserves what is known as the Typikon for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Edited by Athanasios Papadopoulos-Kerameus in the late nineteenth century, this manuscript outlines the elaborate rites surrounding Easter. It specifically describes women with censers—reenacting the Myrrhbearers—censing at the tomb during the late-night Saturday vigil and the Sunday morning liturgies.

In the historical setting of Byzantine Jerusalem, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (the Anastasis) was—and remains—a major site of pilgrimage. Pilgrims reported seeing a domed aedicule enshrining Christ’s tomb, often decorated and incensed by clergy and laity alike. The carved domed structure on the ivory pyxis resonates with these real‐life descriptions. The presence of curtains, steps, and the dangling censer visually ties the scene to the ritual actions recorded in the Typikon.

Significance of Women’s Presence

These images speak powerfully to the place of women in early Christian devotion. While formal ecclesiastical roles for Women at the Altar became restricted in later centuries, the Myrrhbearers were—and remain—venerated as essential witnesses to the Resurrection. Depicting them in such prominent, active stances reminds us of their critical presence within the sacred liturgy. Far from mere bystanders, they incensed the Holy Sepulchre in a sign of prayerful honour, reinforcing the biblical narrative that women were among the first to behold and announce the risen Christ.

Artistic and Devotional Function

Ivory boxes like this often served sacred or liturgical functions—sometimes holding relics, holy oils, or the Eucharist. Placing the Resurrection scene on an object used in Christian ritual further integrated the believer’s daily or festal worship with the central truths of the faith. For many early medieval worshippers, beholding these carved figures may have evoked the actual liturgies unfolding in Jerusalem, forging a spiritual link between a distant shrine and local devotion.

In this small yet richly carved ivory object, we encounter a dynamic fusion of biblical narrative, liturgical practice, and a testament to the revered role of women in the Resurrection story. The Myrrhbearers, with their iconic censers and prayerful posture, embody the theological conviction that all believers—especially women—share in the mystery of Easter. Their raised arms remind us that in early Christian art, prayer transcended clerical boundaries, affirming these faithful women as active participants in the unfolding drama of salvation.

Women’s Roles in the Early Church: Ritual and Liturgical Participation

From the very beginnings of Christian practice, women appear as active participants in communal worship, charity, teaching, and other ministerial tasks. In Romans 16:1–2, for instance, the Apostle Paul commends Phoebe, a diakonos (often rendered “deacon” or “servant”) of the Church in Cenchreae, highlighting a woman entrusted with delivering Paul’s letter and possibly exercising pastoral care. Historians emphasise that such early texts reflect a less rigidly stratified church structure than those that emerged in later centuries.

Deaconesses and Liturgical Service

Evidence from sources like the Didascalia Apostolorum (3rd century) and the Apostolic Constitutions (4th century) outlines specific functions for female deacons, or deaconesses, particularly in baptising and anointing other women. The Didascalia describes them as assisting bishops in ministries of compassion (e.g., visiting the sick or caring for the needy) and sometimes aiding in liturgical roles, such as distributing communion to housebound women. This early witness confirms that women were not merely present but performed meaningful tasks within the worshipping assembly.

Prophecy, Leadership, and Controversy

Scriptural passages like 1 Corinthians 11:5, where women pray and prophesy in the assembly (albeit instructed to cover their heads), suggest that charismatic expressions of faith were open to all, regardless of gender. However, later letters attributed to Paul or his disciples (e.g., 1 Timothy 2:12) and subsequent ecclesiastical rulings indicate a tightening of restrictions on women’s leadership. By the late 4th and 5th centuries, multiple regional synods curtailed women’s ability to publicly teach, preach, or hold liturgical offices. In a 494 CE letter, Pope Gelasius I complained about women “serving at the altars,” revealing that female liturgical participation still persisted in some communities despite mounting ecclesiastical disapproval.

Scholarly Insights

In her seminal study, Karen Jo Torjesen observes, “Women in the earliest Christian communities took on varied ministerial responsibilities—preaching, teaching, administering baptism—reflecting the movement’s more egalitarian ethos at its inception.”<sup>1</sup> Likewise, Elizabeth A. Clark underscores that “the picture of women’s roles in the early Church is complex, shaped by scattered references that, collectively, reveal their remarkable involvement in worship, instruction, and communal leadership.”<sup>2</sup> Far from being silent observers, women offered vital contributions to the spiritual and liturgical life of nascent Christianity.

Liturgical Commemoration

By the time of the Byzantine liturgies at the Anastasis, seen in the Codex Stavrou Typikon (9th–10th century in origin), certain ceremonial functions—such as censing and processions—remained open to female participants, at least in specific re‐enactment roles like the Myrrhbearers. Though formal ecclesial ranks gradually became male‐dominated, the memory of women’s presence in Gospel narratives and early Christian rites persisted, celebrated in art and liturgy as exemplars of devotion and faith.

Women’s Continuing Significance in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Traditions

Despite the longstanding tradition of a male‐only priesthood—grounded in the theological conviction that the priest stands in persona Christi (as Christ was incarnate as a man)—women have always occupied pivotal roles in both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox communities. These roles reflect the conviction that, while Christ is the “new Adam,” Mary is revered as the “new Eve” or archetype of the Church, thus embodying the feminine dimension of salvation history.

Mary as the Image of the Church

Within both traditions, Mary is venerated not only as the Mother of God (Theotokos in the East) but also as a powerful symbol of the Church itself, often described as the Bride of Christ. This Marian model underscores that the Church’s collective witness is profoundly “feminine”—receiving Christ and bringing Him forth in the world.

As theologian Elizabeth A. Johnson writes,

“In Mary, the Church dares to see its own faith and mission, embodied in a woman who became a dwelling place for the living God.”

Thus, even as hierarchical structures remain male, women’s spiritual example, epitomised by Mary, breathes life into the faithful’s communal identity.

Monasticism, Service, and Leadership

In Eastern Orthodoxy, robust traditions of female monasticism have thrived since late antiquity, with abbesses overseeing communities of women dedicated to prayer, charity, and sometimes the operation of schools or hospitals. Likewise, in Roman Catholicism, religious orders of women—Benedictines, Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites, and countless others—have established convents, taught in schools, nursed the sick, and run far‐reaching missionary enterprises. In both Churches, nuns, sisters, and laywomen have often taken on leadership and administrative tasks critical to the Church’s mission. Though they do not stand at the altar as priests, they often become spiritual mothers within their communities—teaching catechism, providing pastoral counselling, or leading retreats.

Theology, Scholarship, and the Public Square

In modern times, women’s theological scholarship has burgeoned. Orthodox and Catholic universities and seminaries now feature distinguished female faculty. Scholars such as Mary B. Cunningham in the Orthodox field and Sr. Sara Butler and Elizabeth Johnson in Catholic contexts have contributed major works on Christology, Marian devotion, and ecclesiology. These women, along with others, exemplify how intellectual leadership can flourish outside of priestly ordination.

As Mary B. Cunningham notes,

“Women’s theological reflections, particularly on the Mother of God, deepen the faithful’s grasp of the Incarnation and reshape how the Church enacts her mission.”

Pastoral Work and Lay Ministry

In parish life—whether Roman or Orthodox—women frequently serve as catechists, choir directors, chanters, readers, youth ministers, and pastoral associates, bearing significant responsibility for nurturing the faith of the next generation. While the priest may celebrate the liturgy and administer the sacraments, laywomen often provide day‐to‐day guidance that sustains a parish’s spiritual vitality. In Eastern Orthodoxy, we also see a revival of the order of deaconesses in some contexts, with limited liturgical and pastoral functions—an echo of ancient practices described in the Didascalia Apostolorum.

The Complementarity of Roles

Drawing on the early Christian insight that Adam and Eve together reflect the fullness of humanity redeemed, Orthodox and Catholic theology alike underscore that the Church needs both male and female expressions of service. If the priest represents Christ the Bridegroom, Mary stands as emblematic of the Church, which receives His life and carries it into the world. In this way, the male role and the female role are seen as complementary rather than interchangeable.

As Sr. Nonna Verna Harrison writes,

“The synergy of male and female service in Christ’s Church manifests the fullness of grace: both roles arise from the Incarnation and together cultivate the life of the Body of believers.”

While the episcopate and priesthood remain male callings within Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, women’s roles are by no means peripheral. Through monastic leadership, scholarship, lay ministry, and the exemplarity of Mary as the figure of the Church, women have enriched and continue to shape Christian faith and worship. Their contributions—both spiritual and practical—stand as a living testament to how the Church’s “feminine” dimension interweaves with its “masculine” ministry, ultimately offering a fuller expression of the Body of Christ.

Mary the Magdalene (Mary of Magdala) in Thierry Murcia’s Research

Thierry Murcia (french historian Doctor in History with highest honours), particularly in the peer-reviewed thesis, Marie appelée la Magdaléenne – I er – VIII e siècle – Entre Traditions et Histoire, and in English his scholarly work published on Academia.edu, offers a provocative thesis that questions the long-held Western tradition of identifying Mary Magdalene as the “repented former prostitute” found in Luke 7:36–50. He points out that this conflation—traced back to Pope Gregory the Great in the late sixth century—was not adopted by either the Greek or the Syriac Churches, nor is it explicitly stated in any of the Gospel accounts themselves.

Instead, Murcia underscores that Luke’s “sinner” remains unnamed, while Mary of Magdala is consistently presented in the canonical Gospels as a prominent disciple and privileged witness of Christ, often appearing at the head of any list of female followers. In fact, she is referenced more frequently than any other woman in the New Testament, suggesting her elevated status at the heart of the early Christian community.

Building on textual analysis, Murcia contends that “Mary Magdalene” is Mary the Mother of Jesus—a claim intended to reconcile the high esteem afforded to the Magdalene with the equally pivotal role of the Theotokos in the early Christian tradition. Within this framework, he challenges Western feminist narratives that have too readily identified Mary Magdalene with sexual sin, effectively overlooking the possibility that she could be the same Mary who bore Christ and symbolises the Church’s receptive, nurturing dimension. By studying Murcia’s expertise, it is evident that many feminist authors obscure the theological depth of Mary’s witness, as recognised by the Greek and Syriac Churches. Together with modern studies, such as The Mary Magdalene Code! The Gospel Revelation of Jesus’ Wife, Murcia’s work compels a re‐evaluation of how the many “Mary” figures in the New Testament have been interpreted—and occasionally misinterpreted—throughout history.

In the forthcoming book My Journey in the Footsteps of Mary Magdalene as a Minister by Sally Elizabeth Jacobs (Tau Sophia Christophora), many questions are addressed with new revelations on women’s roles in the Church. Jacobs also explores the theological understanding and interpretations of the biblical Mary relating to the historical accounts of Mary in Murcia’s thesis. For more on Mary, see two further articles on the Templarkey website: Cultus of Mary Magdalene, Sara & Jesus, The 1st Sacred Pilgrimage and Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Saint Sara La Kali The Rare.

Further reading:

Can girls serve at the altar?

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Circular Letter to the Presidents of the Episcopal Conferences, On the Possibility of Admitting Altar Girls, 15 March 1994.

- Butler, Sara. The Catholic Priesthood and Women: A Guide to the Teaching of the Church. Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2007.

- Ware, Kallistos (Timothy). The Orthodox Church. London: Penguin Books, 1993.

- Harrison, Nonna Verna. Women in the Early Church and Byzantine Monasticism. (Various articles and conference proceedings; see Harrison’s works on Byzantine spirituality.)

Women’s Continuing Significance in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Traditions:

- Johnson, Elizabeth A. Truly Our Sister: A Theology of Mary in the Communion of Saints. New York: Continuum, 2003.

- Cunningham, Mary B. “From Doctrine to Narrative: The Rise of the Panegyrical Homily in Honour of Mary in the Middle Byzantine Period.” In The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images, edited by Leslie Brubaker and Mary B. Cunningham, Farnham: Ashgate, 2011, pp. 11–26.

- Harrison, Nonna Verna. Women in the Early Church: A Study in Byzantine Spirituality. (Forthcoming article referenced in conference proceedings; see Harrison’s other works on Byzantine theology.)

References:

- Ashbrook Harvey, Susan. Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006. This book offers insights into the significance of incense and olfactory practices in early Christian worship.

- Apostolic Constitutions (4th cent.), ed. and trans. F. X. Funk, Didascalia et Constitutiones Apostolorum, 2 vols., Paderborn, 1905.

- Brubaker, Leslie, and Mary B. Cunningham (eds.). The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011. While focusing primarily on the Mother of God, it contains discussions of female devotion and iconography in Byzantine practice.

- Cameron, Averil. Byzantine Matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014. Presents critical methodological perspectives on interpreting Byzantine history and its religious culture.

- Clark, Elizabeth A. Women in the Early Church. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, 1983.

- Didascalia Apostolorum (3rd cent.), ed. and trans. Alistair Stewart-Sykes, The Didascalia Apostolorum in English, Brewer, 2009.

- Eisen, Ute. Women Officeholders in Early Christianity: Epigraphical and Literary Studies. Translated by Linda M. Maloney, Liturgical Press, 2000.

- Papadopoulos-Kerameus, Athanasios (ed.). Analekta Hierosolymitikes Stachyologias. St. Petersburg, 1891. Key edition of the Jerusalem Typikon manuscript (Codex Stavrou), detailing liturgies for the Anastasis, including references to the myrrhbearers.

- Pope Gelasius I, Letter XIV (494 CE), in Patrologia Latina, vol. 59, ed. Jacques-Paul Migne, 1848.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary (ed.). Holy Women of Byzantium: Ten Saints Lives in English Translation. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1996. This book provides a broader context for women’s religious roles and their veneration in Byzantine culture.

- Torjesen, Karen Jo. When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity. HarperCollins, 1995.